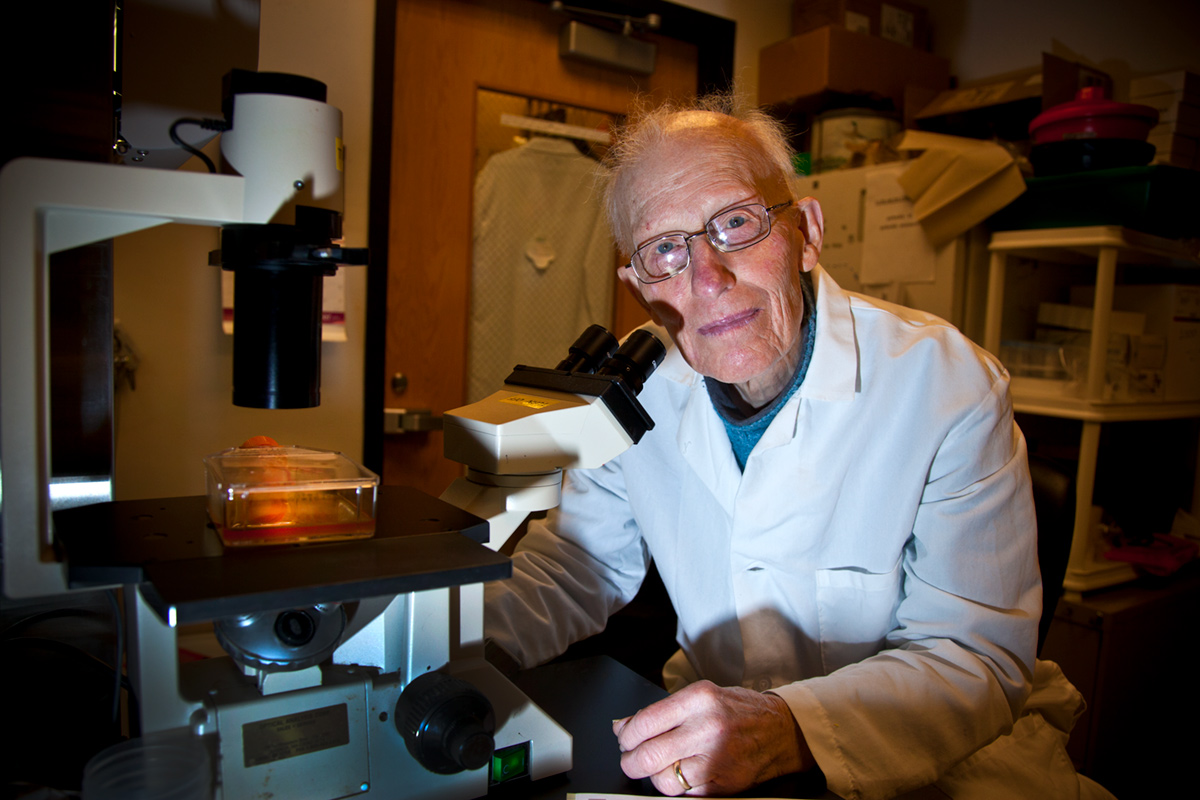

A Lifetime in the Lab

At ninety-three, researcher John Codington is still breaking ground

Kay Hinton

having peppermint tea and crackers at a small table in the break room of the Whitehead Biomedical Research Building, Senior Research Associate John Codington 41C 42G looks out the window onto the railroad tracks running by the Depot. “That used to be a passenger stop when I went to school here,” he says.

The ninety-three-year-old chemist has his own lab space just down the hall, where he comes nearly every day to work in cancer research.

Codington’s journey has taken him full circle, from Atlanta, where his family moved when he was one, to the University of Virginia’s malaria research program, to the National Institutes of Health, to Europe, to faculty positions at Cornell and Harvard, to private biotech companies, and back to Emory.

His primary research concerns the chemical changes in cell surface glycoproteins associated with immunological resistance in tumor cells, and his goal is a diagnostic assay that will detect the presence of a wide range of human cancers.

He hopes to develop a more reliable, consistent way to detect cancers at the earliest stages. “The test must be robust and suitable for clinical use,” he says.

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 1.5 million new cancer cases were reported in the US in 2011, most of which were carcinoma derived.

Codington’s lab isolated epiglycanin (a glycoprotein of a carcinoma cell surface), and recognized that antibodies to epiglycanin signaled a cancer-specific substance in the blood of carcinoma patients.

“We isolated the active component of epiglycanin, which I call Emorin, for Emory,” says Codington, who admits to feeling more himself in a lab coat than street clothes. “We are pretty close to having the final answer but we don’t have it yet.”

Difficulties abound.

Cancer, he says, is so close to being normal that many aspects of a cancer cell are present in normal cells. Also, when dealing with human serum, you are dealing with the entire history of each individual.

“If they have had measles, or mumps, they have those antibodies. All of these things come to bear,” Codington says, “That’s why it’s taking so long, and why no one else has found it.”

As a student at Emory, where he was manager of the swim team and played French horn in the symphony orchestra, Codington studied organic chemistry, graduating with honors and going on to gain a master’s degree in chemistry.

His brother, Arthur Codington 39C 40M, who practiced in Decatur and was an endocrinologist at Grady, and sister, Mary Codington 42G, also attended Emory.

Soon after graduation, Codington was called into service by the US Army’s Office of Research and Development, working through a program at the University of Virginia to develop a better drug for malaria.

“This was during the time of World War II,” he says. “I synthesized a series of 7-choloroquinoline derivatives, and it was my good fortune that this work contributed to the development of chloroquine, which is still used in treating malaria.”

Many decades later, an Emory student who had suffered malaria as a child would thank him for saving her life.

Codington received a PhD in chemistry from the University of Virginia in 1945, and continued his work on malaria at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, until 1949. He has worked at Columbia University, the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, Harvard Medical School, and the Boston Biomedical Research Institute.

After returning to Atlanta, Codington gained the support of Professor of Chemistry Dennis Liotta and Professor of Pathology Charles Parkos, who provided him equipment and space and say he works “tirelessly and enthusiastically.”

Codington says he comes in to the lab most days.

“Some Saturdays I don’t make it in, but on Sundays I’ll come in and coat a plate so I’ll be ready for Monday. Some nights I work until eleven o’clock. I am fortunate that I can still work twelve- to fourteen-hour days and not get too tired,” he says.