The Complexity of Cuba

An Emory group crosses ninety miles of ocean to discover a world of difference

When 329 slaves, including men, women, and children, revolted at Sugar Mill Triunvirato, Matanzas, in November 1843, they were protesting starvation rations; the use of hand, foot, and neck shackles; and generally grim working conditions.

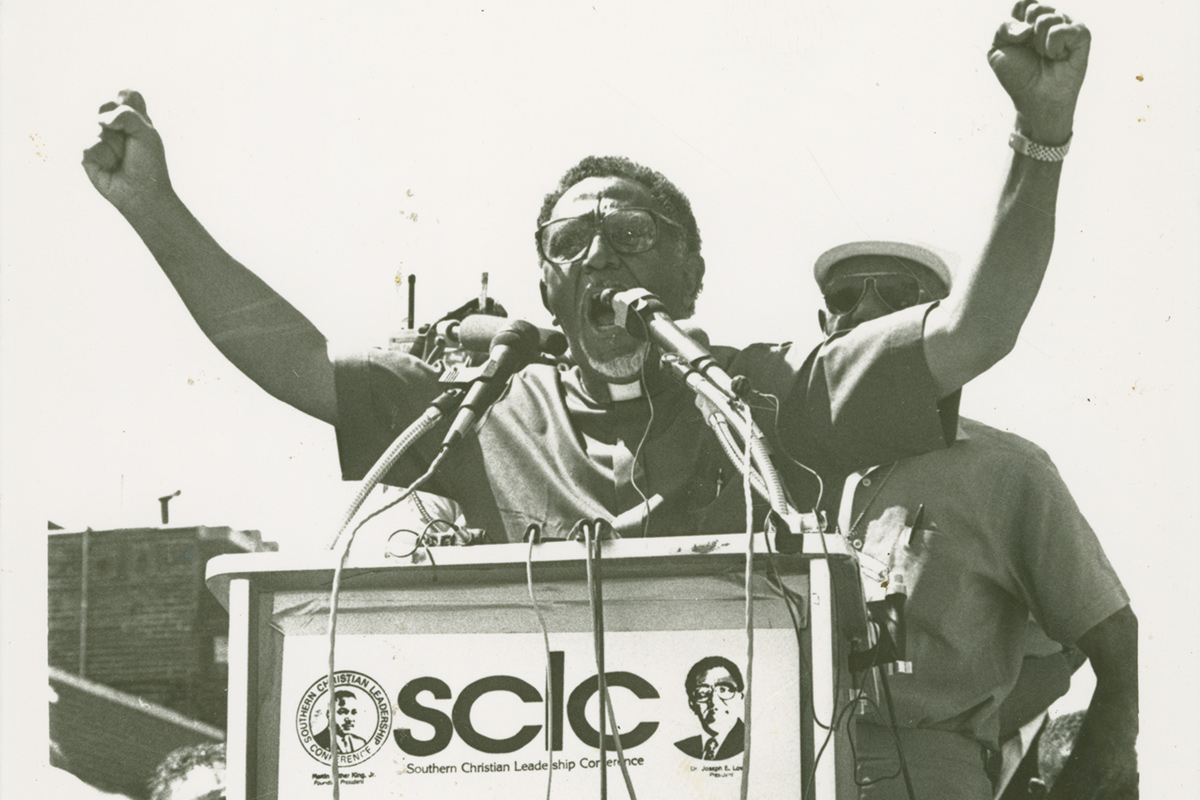

The Shoulders of Giants: Emory's Journeys group (top) stands in front of the monument to the 1843 slave rebellion in Triunvirato.

Michael Leo Owens

A woman, Carlota, was one of three leaders of the revolt. They burned the main house and took up machetes to defend themselves.

Ultimately, the rebellion failed. Sixty slaves were killed, including Carlota; seventy-nine had trials and were either jailed or punished at the mill. But discontent had spread to other mills, and the thought of freedom had taken hold.

All that remains of the scene today are a few scattered buildings, including the nursing quarters and the drying house, and a towering monument to the enslaved workers of the plantation. Carlota, a national icon of sorts, stands strong in the middle, arms spread and machete raised.

Maricela Velasco, a descendent of slaves, gives tours of the former sugar mill.

Jarvis Dean 13C

"My great-grandparents were slaves," said Maricela Velasco, standing by the old stone wall next to planting fields now grown wild. "In Cuba, by law, all of us are the same. Institutional racism doesn't exist. In people's minds, yes, racism is passed down. But with each generation, it gets less. I work in the rescue of our [Afro-Cuban] traditions."

Cuba, whose native Indian population was all but wiped out by Spanish colonialism in the 1500s, once had an estimated 1.3 million enslaved workers imported from Africa—more than the US. At one point, slaves outnumbered residents on the island, a history that has left a complicated racial legacy in the communist nation of eleven million.

Of course, as tour guide Laura Gonzalez Gandarilla said, "In Cuba, everything is complicated."

A Journeys group from Emory visited Cuba for ten days in May to try to untangle issues of race, religion, and reconciliation. Journeys, a program of the Office of the Chapel and Religious Life, enables Emory students, staff, faculty, and alumni to visit parts of the world that have undergone internal and external conflict.

Since Cuba, ninety miles south of Florida, is still under economic embargo and travel restrictions from the US, the group gained permission to visit under a religious license issued by the US Treasury, and took a forty-minute chartered flight from Miami into Havana's Jose Marti Airport.

The Journeys group—Associate Dean of the Chapel and Religious Life Reverend Lisa Garvin 03T; Muslim Religious Life Adviser Isam Vaid 93Ox 95C 98MPH; Journeys coordinator Cynthia Shaw; Associate Professor of Political Science Michael Leo Owens, health care administrator Karen Cobham-Owens; Michael David Harris 13C; Jarvis Dean 13C; Christine Hines 13C; Adam Loftus 14C; Candace Pressley 15C; Emilia Truluck 16C; and Nicole Morris 17PhD—stayed in the Hotel Habana Libre, formerly the Habana Hilton and famous as the spot where Fidel Castro set up his offices on the twenty-third floor for a few months after the 1959 revolution.

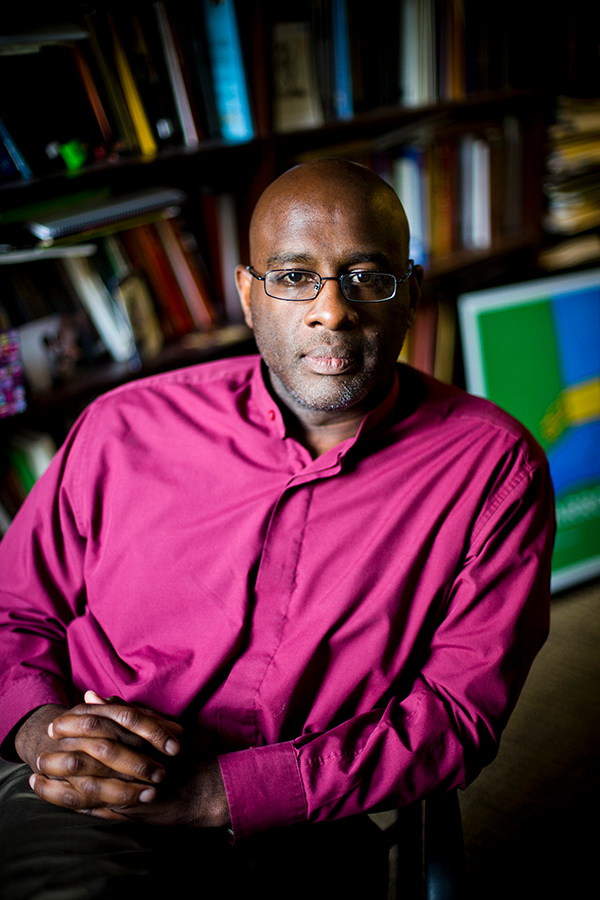

Emory Professor of African American Studies and English Mark Sanders is an expert on Afro-Cuban culture and literature.

Bryan Meltz

Emory Professor of African American Studies and English Mark Sanders, editor and translator of A Black Soldier's Story: The Narrative of Ricardo Batrell and the Cuban War of Independence, is a frequent visitor to Cuba and an expert on Afro-Cuban culture and literature.

"The [Cuban] Revolutionary Army, or the Liberation Army . . . was between 60 and 80 percent black, so blacks in the army were overrepresented," Sanders says. "The cause of Cuba Libre was not simply a fight against Colonialism and Spanish occupation, but the larger cause was a new egalitarian society, one free of racial discrimination."

This dream has been only partly realized, says Sanders, who spoke to the Journeys group before they left. Racial bias still influences the wages, opportunities, and housing afforded to Cubans of African ancestry. "But there is a difference [from the US] that you notice almost immediately," he says. "Cubans will say they are Cubans first, not Afro-Cubans. Nationality before race."

The Emory group visited historic sites such as Playa Giron (the Bay of Pigs) and Revolutionary Square, with its building-high likenesses of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos, and visited a surprising array of churches, from Catholic to Greek Orthodox, a synagogue service, a Methodist seminary, and a Muslim prayer service in an imam's home. Tours of a community center for older Cubans and a Jewish center's program for children resulted in impromptu singing and dancing. Cultural experiences like cigar rolling (and sampling), a cabaret show and a jazz club, a farmer's market, and an afternoon swimming in the warm turquoise waters of the Straits of Florida offered chances to mingle with locals.

Che Guevara's likeness on the building of the Ministry of the Interior towers over Revolution Square.

Christine Hines 13C

At the slave museum in the Spanish fortress San Severino Castle, built more than three centuries ago to protect Havana from attack by pirates, the group saw artifacts and viewed artwork inspired by slavery and the influence of African traditions on Cuban culture and religion, including the merging of African religions and Catholicism into belief systems like Santeria. They also had a chance to speak to a Santeria priest and doctor at the Afro-Cuban religious center Cabildo Quisicuaba, which sponsors social programs to help people who suffer from mental illness, addiction, or HIV.

Christine Hines 13C

Meals of freshly caught fish, shredded pork, chicken, beans and rice, mango juice, and tropical ice cream were taken at paladars (in-home restaurants), and almost nightly the students walked from the hotel to watch the sunset from the Malecon, the sea wall along a main boulevard in Havana.

"I haven't seen racism on the streets that compares to the racism in America, at least not in normal, everyday situations," says Michael Harris, who graduated in May with a bachelor's degree in philosophy. "You see darker shades of people and lighter shades together, socializing, partying—there doesn't seem to be segregation. The first marker of identification and difference in the US is race, and I don't see that being the case here."

"If I were poor, I'd rather be in Havana than Atlanta," says Jarvis Dean, also a recent Emory graduate in art history and visual arts, referring to the modest rations card provided by the government, free housing, and medical care. The majority of Cuban workers are employed by the government, but make an average of $20 a month.

Emory Journey participants Isam Vaid and Michael Harris talk under a flame tree in John Lennon Park in Havana.

Christine Hines 13C

Toilet paper and other paper products, clothes, household goods, cars, toys, and food are mostly imported and can still be scarce and very expensive—which explains the fleet of still-functioning American cars from the 1950s and 1960s, many of them in use as taxis. Still, things are better than during the early 1990s, after the Soviet Union withdrew support and the island went through a deep recession called the Special Period, with blackouts, severe shortages of goods, and barely enough food.

A loosening of restrictions after Raul Castro came to power in 2006 has led to a boom in street vending and home businesses.

Emory religious life adviser Isam Vaid says that while he was surprised by the lingering poverty, he was also struck by "the creativity of the Cuban people to engineer solutions and devise ways to make extra money," especially in CUCs, the tourist currency.

While locals use Cuban pesos, tourists must change their money into CUCs; one CUC equals about one dollar, but a percentage is taken for the government from each exchange. Tourism is one of the main industries of Cuba, bringing in about two billion dollars a year, and remittances sent home to Cubans by relatives and friends who have left are also thought to be in the billions.

A mosaic sculpture at artist Jose Rodriguez Fuster's colorful home. Much of the artwork in Cuba is African-inspired. "The ability of the black communities on the island to retain cultural and religious beliefs and practices from Africa was amazing," says Nicole Morris 17PhD.

Michael Leo Owens

Emilia Truluck, a sophomore at Emory whose ancestry is Cuban, says unlike countries in which poor children, and especially girls, don't have the "opportunity or obligation to go to school," she was impressed when touring a Cuban elementary school to learn that "every child, regardless of gender or race, was in school and present daily—otherwise the teacher would visit the house of the child."

The strength of the Cuban people "in the face of historical political and economic oppression is amazing to me, " Truluck says, "and seeing them made me very proud to claim that I have a few drops of Cuban blood."

At the artist's alley Callejon de Hammel, a community project showcasing local art and music, the group's guide, Elias Aseff, said that racism in Cuba is "very soft, not so cruel as in other countries," pointing out the street's striking Afro-Cuban inspired art.

Indeed, Nicolas Guillén, a mulatto Cuban poet, wrote: "Cuba's soul is mestizo [mixed race]. And it is from the soul not the skin that we derive our definitive color. Someday it will be called 'Cuban color.' "

One organization trying to enhance equality and respect for all at a grassroots level is the Martin Luther King Center in Havana. Founded as an ecumenical organization in 1987, it operates on the principles of Christian Liberation theology—or, as its magazine's editor, Esther Perez, explained, "doing something real with real people in a real community." On an inside wall of the center is a mural of King holding the dove of peace.

Of course there is racism in Cuba, Perez said, but, "if you are trying to find racism like there is in the US, you will fail. Racism is cultural, and it depends on the country's cultural past. We had the first real interracial army in Cuba, with blacks in the ranks as officers. One of our 'founding fathers' is black. The 'mother of Cuba' is black."

After the revolution, the government's method of combating racism was to ignore people's race. Everyone was simply called "citizen," and that was the only word accepted in documents. Beaches, walking paths, and parks were integrated. Education, even higher education, was free and denied to no one. But color blindness proved not to be a panacea.

A portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. at the ecumenical center named for him in Havana.

Jarvis Dean 13C

"The population took ahold of and benefited from these opportunities, yet it did not eliminate racism," Perez said. This was especially apparent during the Special Period of the 1990s, she said. "Economic crises never come alone. They trigger other crises, such as the idea that there are people 'less' than others."

As in most parts of the world, Perez said, "racism is an ongoing struggle we are waging even now."