Time Marches On

A varied collection housed at Emory offers new insight into decades of work by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, including the years following the death of its iconic leader, Martin Luther King Jr.

It's true that after the 1968 death of its charismatic and celebrated leader, and with victories secured in its most clearly defined battles—civil and voting rights—the SCLC would not again capture national media attention as it had in its early years. But the organization did not fade away after King's death. In fact, it still operates today, with headquarters on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta—just a few miles from the Emory campus.

King, Abernathy, Joseph Lowery, and other Southern ministers founded the SCLC in Atlanta in 1957 as an outgrowth of the Montgomery bus boycott. With an initial focus on protesting segregated transit systems in the Jim Crow South, the group's mission expanded to encompass voting and civil rights. The SCLC was behind some of the most significant nonviolent protests of the sixties, including the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the fiftieth anniversary of which will be commemorated this summer.

And the Struggle Continues: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference's Fight for Social Change

The exhibit, curated by Carol Anderson, Michael Ra-Shon Hall, and Sarah Quigley, is on display now through December 1 in the Schatten Gallery on Level 3 of the Robert W. Woodruff Library.

Now historians and the public alike have an unprecedented opportunity to learn more about the inner workings and ongoing efforts of the SCLC, thanks to a voluminous collection of the organization's archives housed at Emory's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL). While the SCLC Collection at MARBL includes materials covering the fifty-year span from the SCLC's inception through 2007, most of the materials focus on the post-King years, a period that was underdocumented in national media and has been underrepresented in holdings at research facilities.

The SCLC after King

Abernathy, King's close friend and appointed successor, led the SCLC following King's assassination through 1977. Under his leadership, the organization focused on antipoverty programs and preserving the rights gained through SCLC's earlier efforts.

Abernathy was succeeded by Lowery, who led the organization for two decades and expanded its work overseas—most notably with protests against South African apartheid—and shifted its focus at home from voting rights to crusades against drugs and gun violence and campaigns to raise awareness about the lack of health care in poor and minority communities.

Since Lowery's retirement in 1997, the organization has been through a series of leadership changes, with presidents including Martin Luther King III; Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, one of the SCLC's original cofounders; King's nephew Isaac Newton Farris; and Alabama legislator Charles Steele.

The MARBL collection, acquired for an undisclosed price from the SCLC by Emory in 2007, is massive—literally. Just opening the one-thousand-plus boxes to get an overview of the materials took a month, says MARBL Manuscript Archivist Sarah Quigley, who was hired in 2009 to oversee the processing of the collection. "Some of the boxes hadn't been opened for thirty or forty years," Quigley says."

As Quigley and her team—a total of eleven students and archivists worked with her during the project's three-year span—began to explore the materials, they were particularly struck by the extent of SCLC's work after King's death. Previously, "I didn't realize they were still in business; I thought they'd closed down after the 1960s," says Quigley.

Michael Ra-Shon Hall 11G 16PhD, who is pursuing a doctoral degree in Emory's Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts and worked with Quigley on the collection processing, says he had a "cursory knowledge" of the iconic King years, but also was not aware of the SCLC's later efforts until joining the MARBL team.

Both Quigley and Hall say that as they processed the materials, they were impressed most by the relevance of the SCLC's work to issues today. "It wasn't always in the national spotlight," says Hall. "But their effort to preserve the rights of the poor, voting rights, gun violence, and access to health care, these are all things that are relevant now."

Connecting the organization's history with today's vital issues and debates is the theme that carries through And the Struggle Continues . . . , an exhibit of more than two hundred items from the SCLC Collection that Quigley and Hall cocurated with Carol Anderson, associate professor of African American studies. The exhibit documents the challenges the SCLC faced while advocating for rights in a country eager to move on from its legacies of slavery and segregation without considering their lingering impact on the education, wealth, and well-being of the people they'd oppressed.

As Anderson wrote in the exhibition curators' statement, "The forces that maintained inequality were as powerful as Jim Crow, but more elusive and harder to define and identify. In addition, those who felt the brunt of continued inequality did so without the shield of respectability to garner public sympathy and outrage. Poor, incarcerated, or afflicted with HIV/AIDS, they found themselves instead consigned to the 'unworthy.' "

The exhibit, which opened earlier this year in the Woodruff Library's Schatten Gallery and continues through December 1, provides an overview of the SCLC's work in the post-King years and also showcases the variety of materials in the archive. Quigley conducts guided tours of the exhibit, and walking through the artifacts underscores how different generations perceive the SCLC's place in history, says Hall.

"Older folks will gravitate to the founding, King's iconic leadership and assassination, and the Poor People's Campaign," he says, while younger visitors are drawn to "materials from the 1990s, like 'Rappin' for Our Future' and gun buyback programs."

Introducing the 'Ground Crew'

SCLC education director Dorothy Cotton instructs a Citizenship Education Program class.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

Researchers, scholars, and authors have been delving continually into the collection at MARBL since it opened in May 2012, says Sara Logue, research and public services archivist.

Deric Gilliard used the archive while completing his master's degree at Georgia State University in 2012 and is back at MARBL researching a biography of Lowery. Gillard says the wealth of materials can be almost overwhelming: "There are eighty-six boxes specifically covering part of Lowery's twenty-year span as president. And then hundreds going back to the founding and his involvement since 1957."

Gilliard, author of Living in the Shadows of a Legend: Unsung Heroes and Sheroes Who Marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., worked at the SCLC for a few years in the 1990s, and says that he has been especially moved by the way the archival materials reveal the hard work of lesser-known staff members who toiled in the decades before his time at the SCLC. In sifting through hundreds of documents, he says, researchers continually "run into the ground crew," or the regular people behind the history-making events.

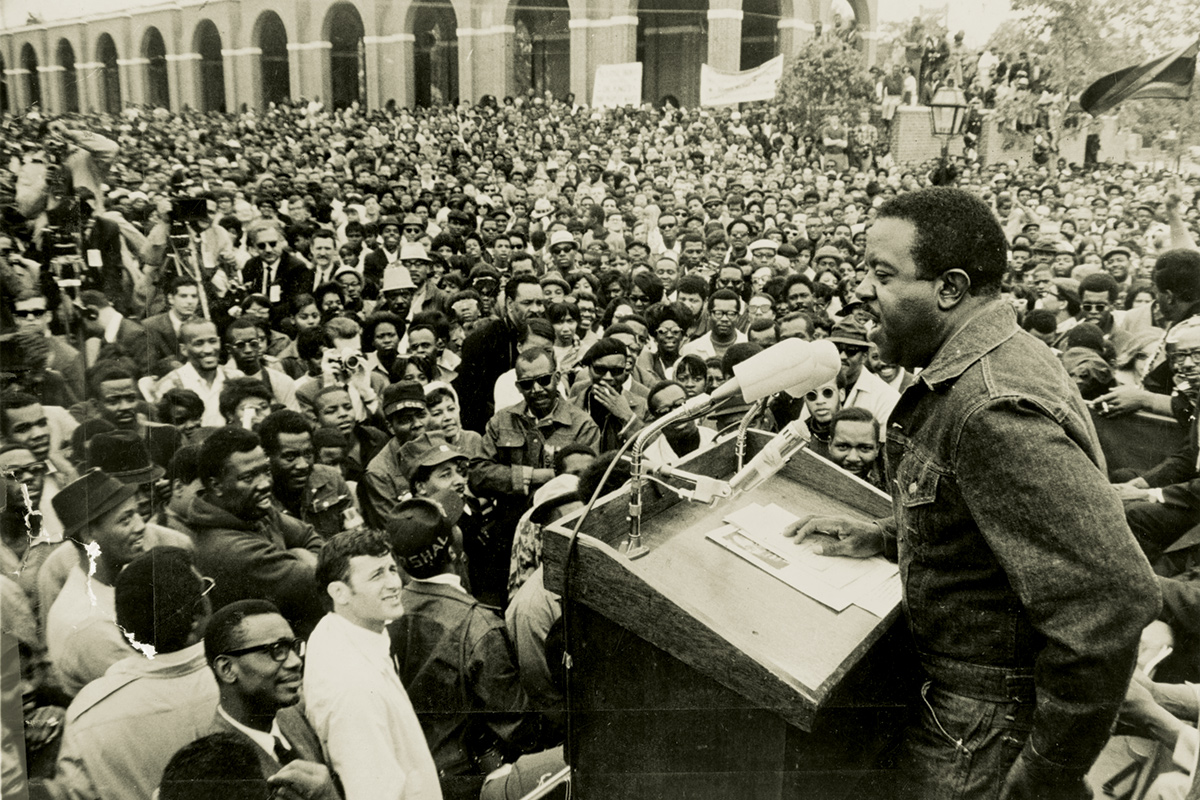

Members of the "ground crew" are featured in the exhibit, and several attended its formal opening in February. They included Brenda Davenport, who oversaw youth programs; Dorothy Cotton, who was the SCLC education director during the King years; and Reverend Dr. Bernard Lafayette, a key logistics organizer during the Poor People's Campaign and other SCLC initiatives, who still sits on the SCLC board and also serves as distinguished scholar in residence at Candler School of Theology.

SCLC organizer Bernard Lafayette (right), now a scholar in residence at Candler School of Theology.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

During a private tour of the exhibit, Cotton marveled over the wealth of material and the memories that it brought flooding back. Peering at a photo of herself, she exclaimed, "I was quite a song leader back then! Music was a motivator. It helped us express what we were feeling."

Later, Cotton added, "I'm glad you all have this. None of us thought about preserving this. It is history."

"You were too busy making it," responded Randall Burkett, curator of MARBL's African American Collections.

At the public opening, civil rights leader and Georgia congressman John Lewis addressed guests, noting, "It is fitting and proper for these papers, these records, to be located here in the heart of the American South, right here in the city of Atlanta, right here at Emory University."

The addition of the SCLC Collection to MARBL's holdings bolsters Atlanta's position as the epicenter for conversations about civil and human rights, and addresses both the historical context and contemporary issues, says Doug Shipman 95C, CEO of the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, which is scheduled to open in 2014.

"Atlanta's depth and quality of materials related to the American civil rights movement provide a tremendous resource for scholars and exhibition facilities," says Shipman. "The prominence of these materials also enhances Atlanta as a destination for academic conferences, visiting scholars, and cultural tourism."

In addition to the coming national civil rights center, Atlanta's civil rights resources include the King historic district, the King Papers at Morehouse College, The Carter Center, and archives at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change.

And more discoveries are still to come, says Shipman. "The significance and scope of the various holdings also improves every institution's prospects of attracting new donations of material in the future," he says. "Significant papers, photos, and items still reside in activists' basements and attics, and I believe much of that material will end up in Atlanta in the coming years."

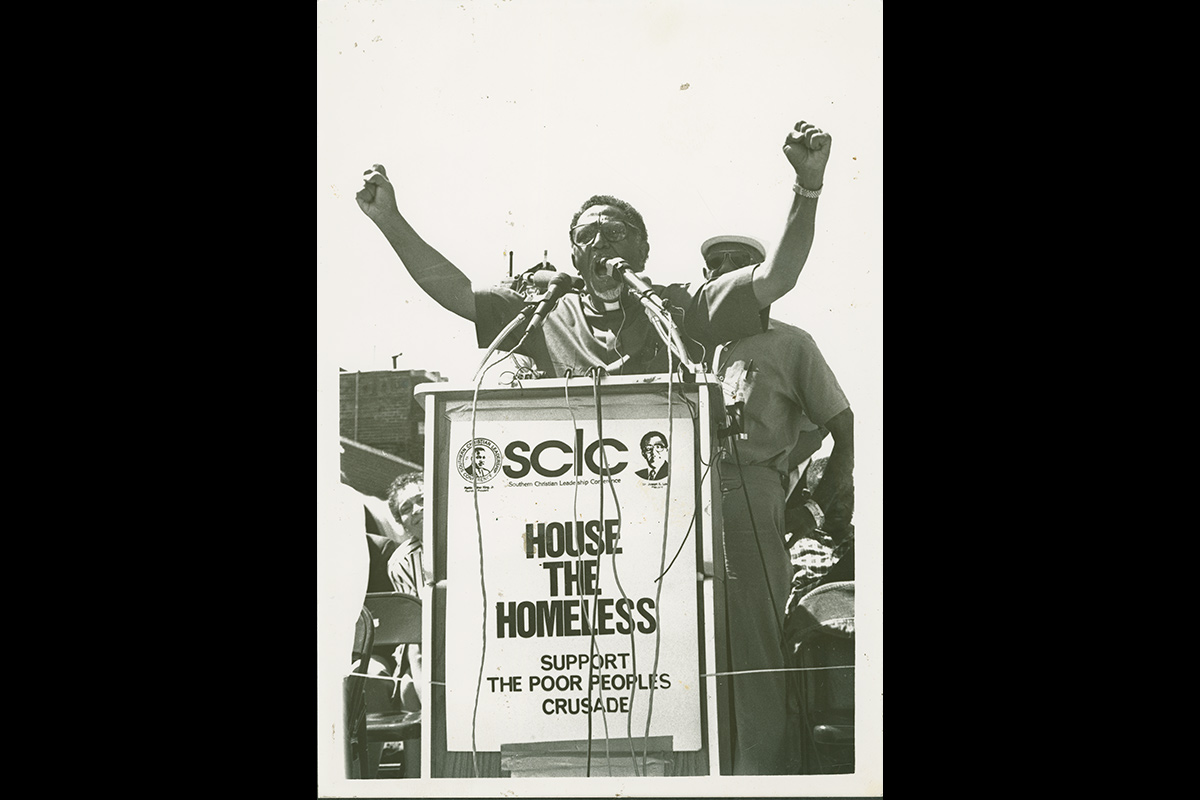

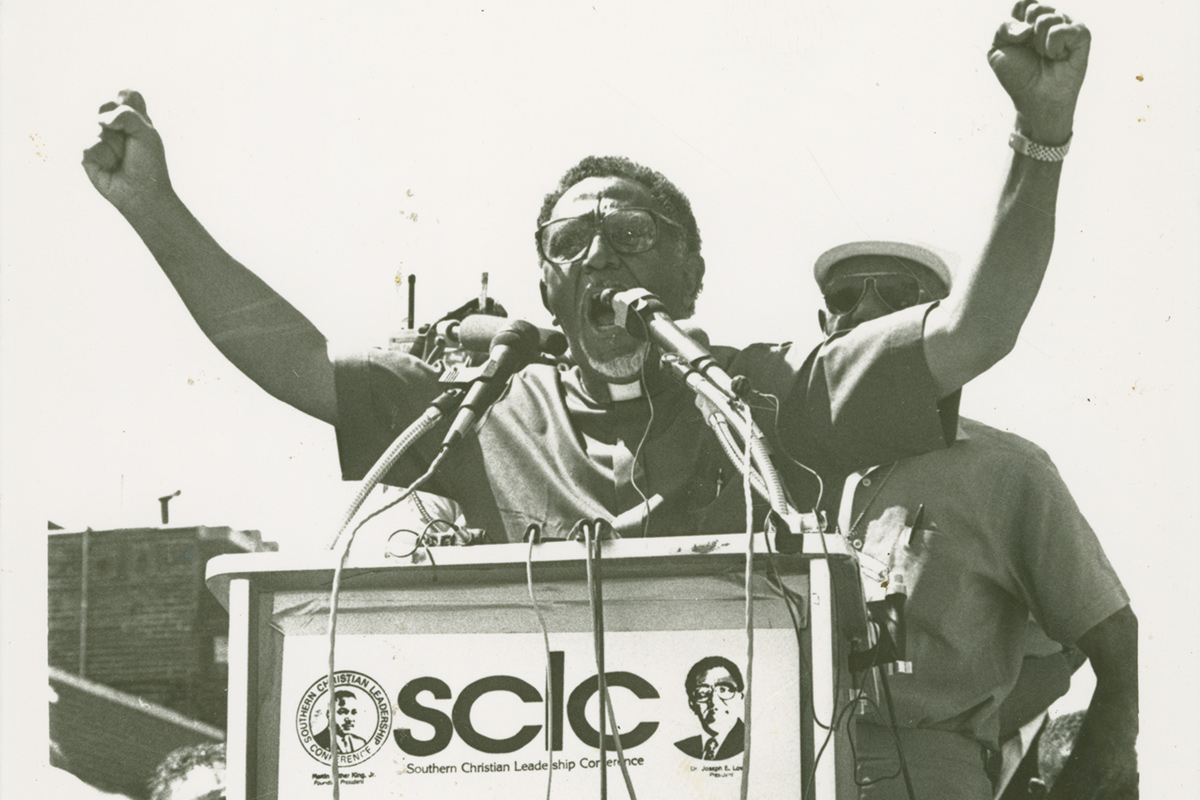

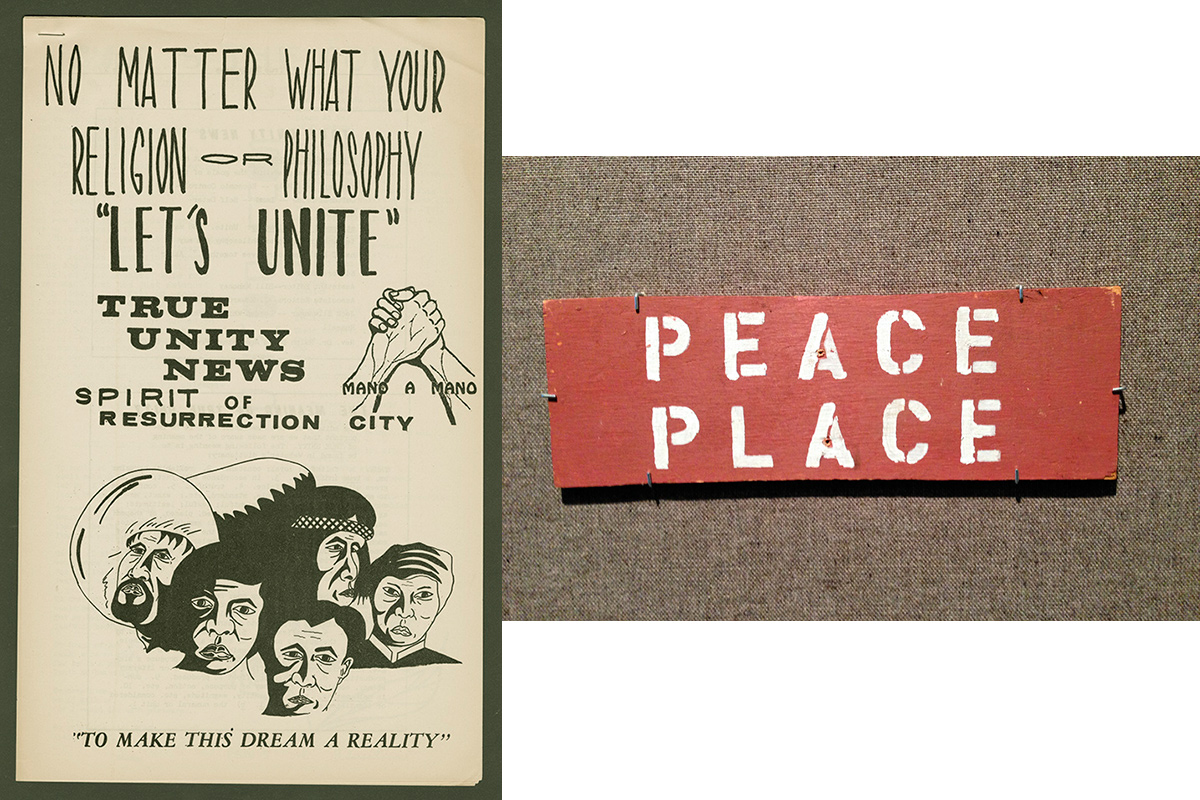

The 1960s: Poor People's Campaign

Planned in the months before King's assassination, this crusade was intended to spark national awareness of poverty, and particularly to get attention on Capitol Hill and in the White House. Heavy on symbolism, the Poor People's Campaign included a caravan of mule wagons bringing diverse ambassadors—Native Americans, Appalachians, urban Puerto Ricans, rural Southern sharecroppers—to Washington, D.C.

In the aftermath of King's death in 1968, the SCLC moved forward with the plan, but the leadership void contributed to chaos at Resurrection City, an encampment plagued by disorganization, reported crime, and sheer bad luck: summer storms flooded the hastily erected village of tents and wooden lean-tos.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

Materials in the SCLC collection provide insight into the inner workings of the campaign and underscore its magnitude. Researchers now can glean firsthand details—program logs, public relations fact sheets, the entertainment arranged for soggy campers—or the evolution of SCLC policies, such as drafts of the "Statement of Demands for Rights of the Poor."

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

The collection provides a multidimensional look at the campaign, through documents such as a hand-drawn map of the encampment and newsletters distributed to protestors; artifacts like Resurrection City "street signs"; and a trove of photographs capturing the gritty experiences of three thousand protesters during six weeks. Audiovisual gems include promotional spots recorded by Marvin Gaye, Marlon Brando, Ossie Davis, and Bill Cosby.

Ralph David Abernathy addresses the crowd

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

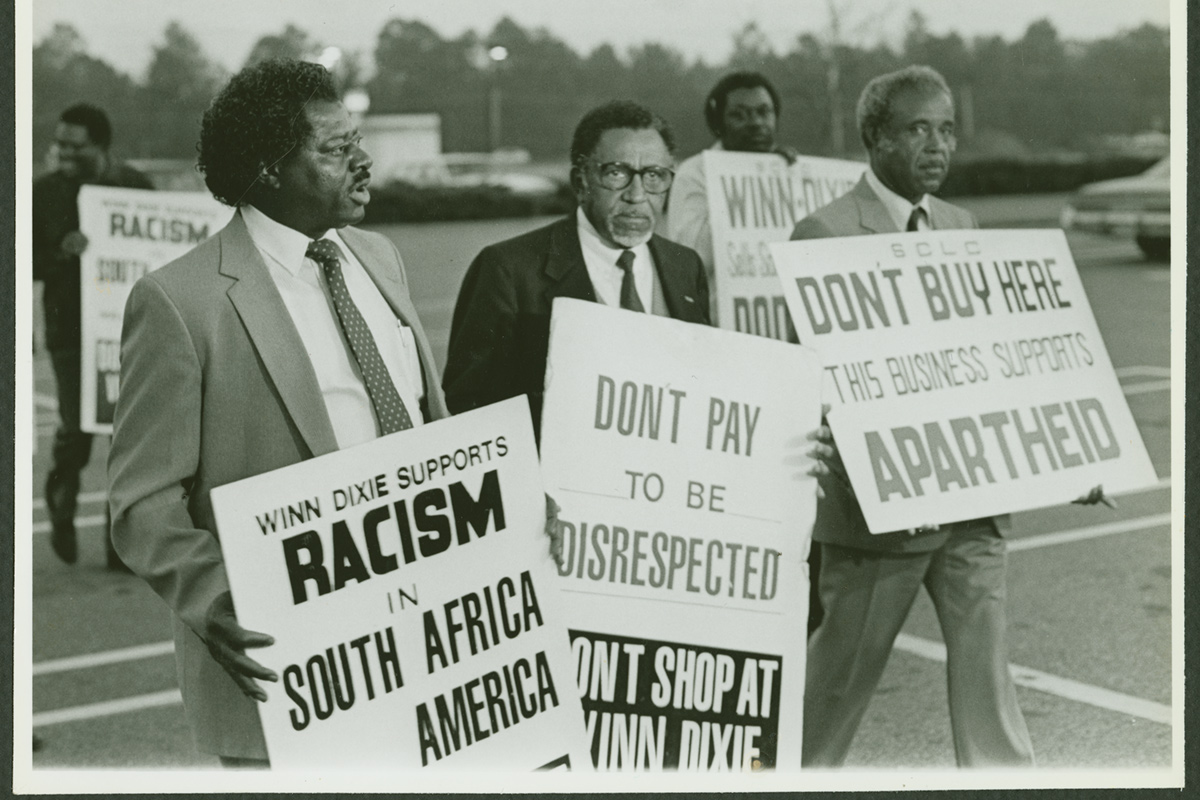

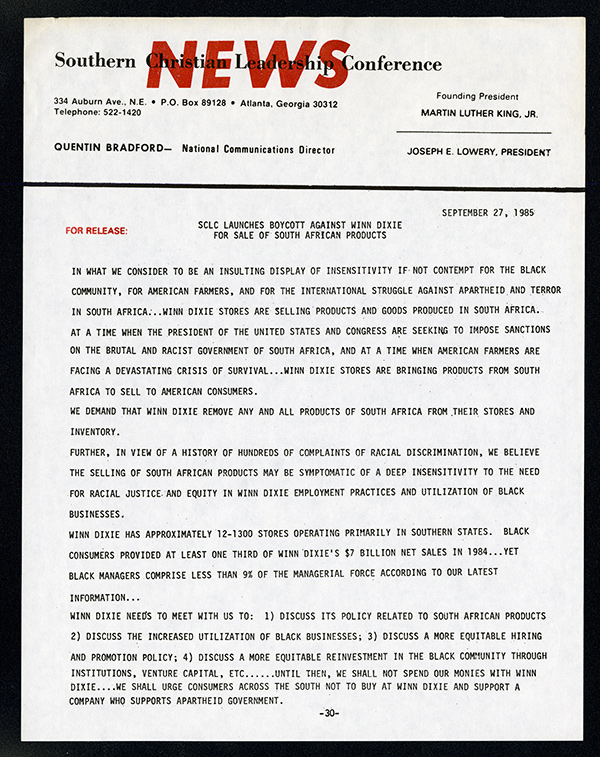

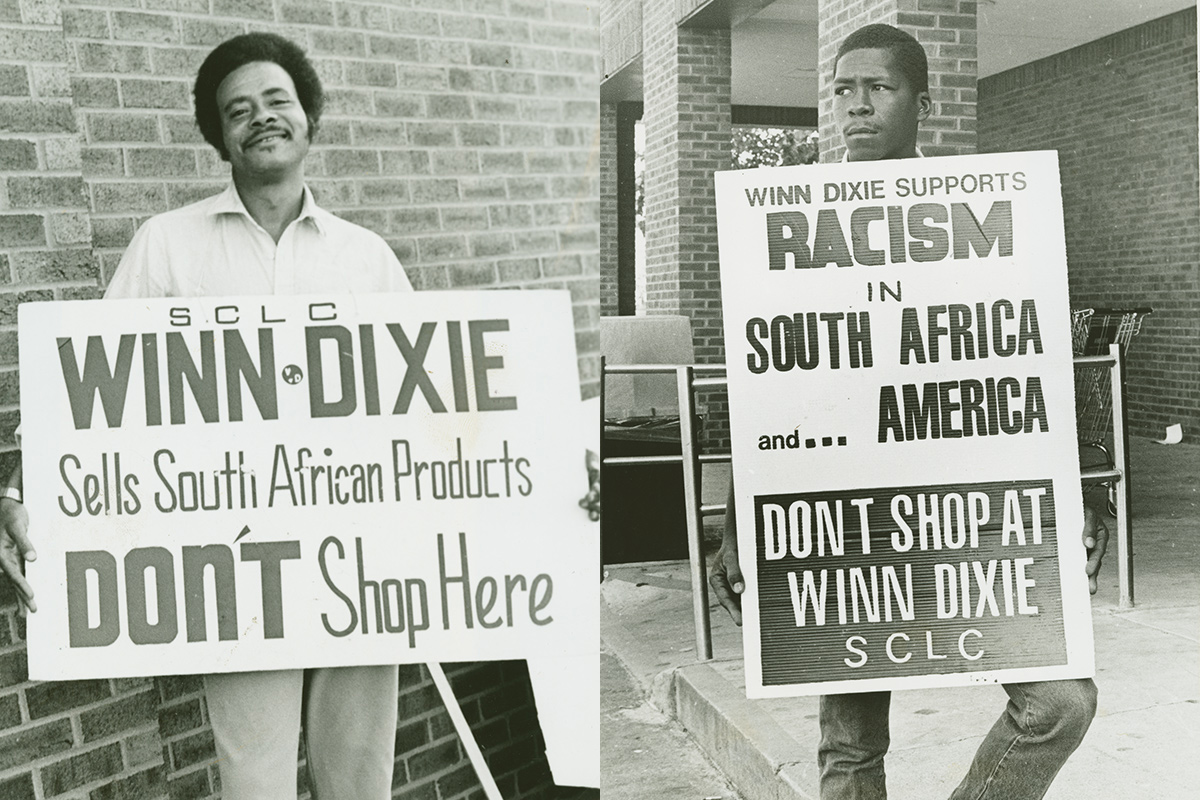

The 1980s: Winn-Dixie Boycott

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

An attentive shopper noticed that her Winn-Dixie store stocked canned fruit and frozen fish produced in South Africa, and notified SCLC Women, the offshoot organization run by Evelyn Lowery, wife of long-tenured SCLC president Reverend Joseph Lowery. As the SCLC staff dug deeper, they learned the supermarket chain—which attributed 22 percent of its sales to black customers—had minimal African American representation in management and virtually none in its executive suite.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

The subsequent SCLC-organized boycott of the supermarket drew on tactics of the organization's early days such as silent protests, sandwich-boarded marchers, and nonviolent sit-ins that resulted in arrests. Among those booked during an Atlanta protest were King's children Bernice, Yolanda, and Martin Luther King III.

Items in the archive include photographs of veteran protest leaders such as Joseph Lowery and youthful volunteers.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

The SCLC distributed fact sheets and fliers to supporters, while Lowery's office communicated by telegram with Winn-Dixie and other corporations with ties to South Africa.

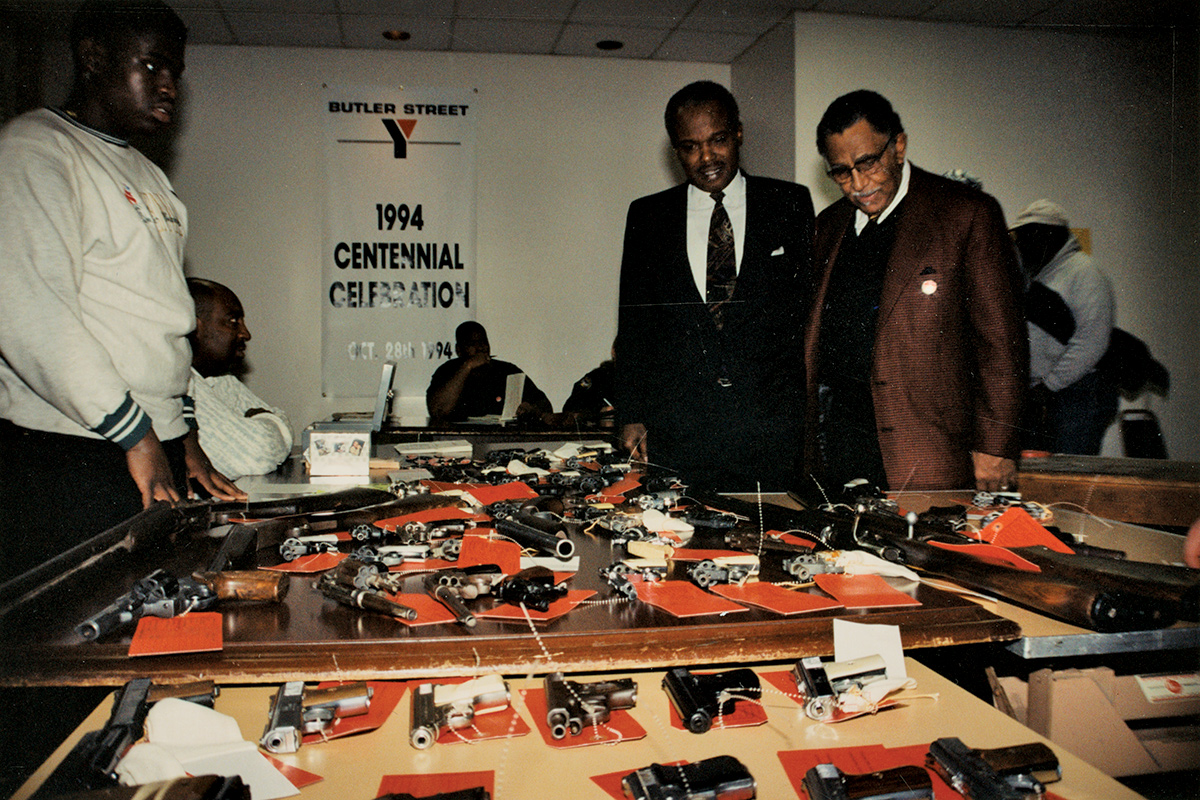

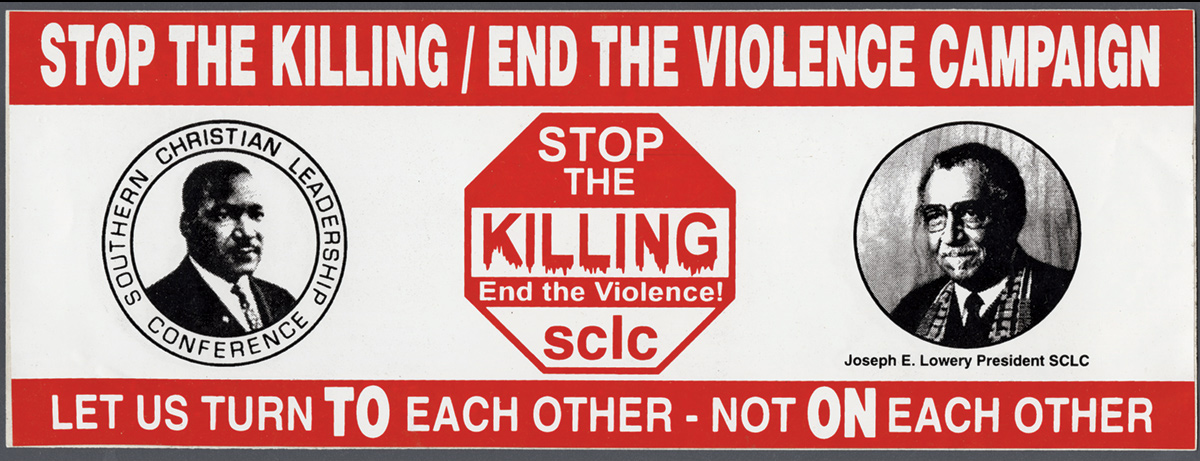

The 1990s: Stop the Killing / End the Violence

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

In response to the crack epidemic and urban gun violence, the SCLC launched a twofold awareness campaign that included antidrug education and instruction in the organization's nonviolent philosophy. The most notable component of the program was the SCLC's support of gun buyback events in cities nationwide. In addition to staging events and raising funds for the weapons exchanges, the SCLC produced training materials for other organizations.

Among the trove of materials from this campaign are bumper stickers and fliers, as well as photographs of high-profile buyback events, such as these in Atlanta.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

The organization's files also provide the opportunity to explore the expanding role of women in the SCLC, such as Gayle Watts-Wiggins and SCLC counsel Roxanne Gregory, who ran the gun buyback program.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference records, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

Rebecca Burns is deputy editor of Atlanta Magazine, the author of three books on Atlanta history, and adjunct professor of journalism at Emory.

Email the Editor