Creative Culinaria

Alumni draw national attention by finding their way to hungry hearts

Inventing success

A shared love of good food has propelled the success of both entrepreneur Brian Rudolph 12B and restauranteur Aaron Vandemark 97OX 99C, who have been recognized for their influence on food both locally and nationally.

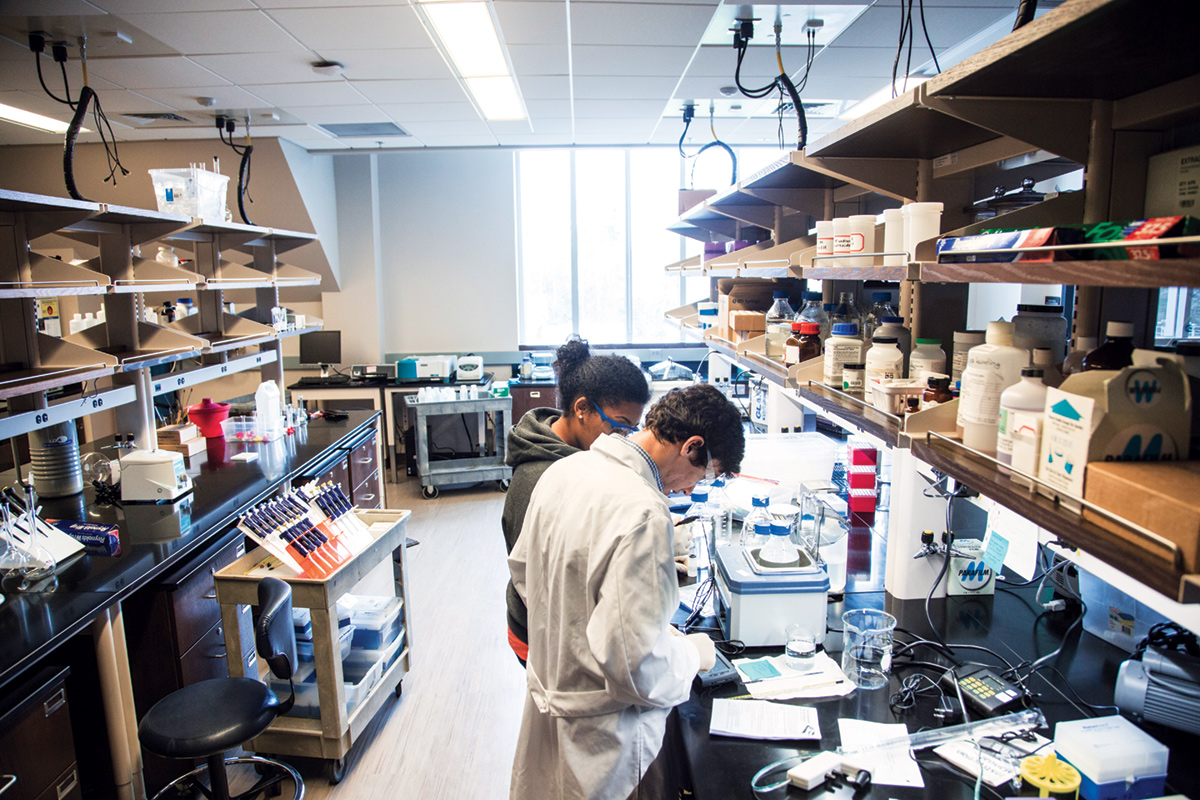

When a doctor told Rudolph to cut gluten from his diet, he struggled to find a satisfying, non-wheat pasta alternative in grocery stores. Eventually, he decided he’d have to make it himself—from chickpeas.

“In 2013, I began experimenting in my Detroit kitchen with a few pounds of chickpeas and a small hand crank. After ten months of trial and error, I made a batch that tricked my roommate into thinking he was eating traditional pasta,” Rudolph says.

As a member of the first class of Venture for America—an effort geared toward revitalizing the city of Detroit through entrepreneurship—Banza pasta was born after a successful crowdfunding campaign. And the young company has skyrocketed to success after formally launching in 2014. Banza has released four different pasta shapes sold in nearly two thousand stores across the country, ranging from Shoprite to gourmet destination Eataly. Banza has been featured in Fast Company, became Fairway’s No. 1 selling pasta, and most recently was named one of Time magazine’s “Best Inventions of 2015.”

Nutrition plays a key role in Banza’s game plan. “Banza is the first to crack the code on chickpea pasta,” says Scott Rudolph, Brian’s brother and Banza’s cofounder. With double the amount of protein as traditional pasta and four times the fiber per serving, Banza also has a lower glycemic index, half the net carbs, and fewer calories than traditional pasta.

Rudolph also is proud to support his hometown, with the company creating thirty new manufacturing jobs in Detroit.

“The city has fallen on hard times, but we take a great deal of pride in contributing to the resurgent culture of manufacturing and entrepreneurship,” he says.

Farm to Belly

In the heart of Hillsborough, North Carolina, tucked into a brick building among local businesses including a knit shop and a farmer’s market, Vandemark runs Panciuto (Italian for potbellied), “a Southern restaurant serving Italian dinners.”

An economics major at Emory who thought his future would center on spreadsheets in the corporate world, Vandemark began a risky journey into the role of restaurateur in 2006, a move that has been defined by his passion for using predominately local food resources on his ever-changing nightly menu. His gamble paid off, as Food and Wine magazine nominated Vandemark in 2011 as “The People’s Best New Chef,” and the restaurant has been featured in the New York Times, Bon Appetit, and Garden and Gun. Locally, Panciuto has been named to “Best Restaurants in the Triangle” for the past five years.

“Economically, being conscious about how we source our food allows key dollars to stay within our community,” says Vandemark. “The fun in sourcing 95 percent of our food from area farms is that we exist within the ebb and flow of the seasons, and that necessitates an ever-changing menu. That people are willing to eat here without knowing what’s going to be on the menu on any given night is very gratifying.”

The restaurant’s garden-sourced menu changes nightly based on availability.

“Cooking exclusively within this framework, connecting bellies to farms, dinner at Panciuto is both distinctly Italian and familiarly Southern. I connect to the people growing the food,” Vandemark says of the dozens of small farms that provide Panciuto with meats, grains, and produce. “What I had not anticipated was that these farmers would become my friends and that these personal relationships would come to define both the way I cook and enmesh me in a community that is food-centric, progressive, and mostly pulling in the same direction towards sustainability.”—Michelle Valigursky