Cult Following

Led by archaeologist Bonna Wescoat, an Emory team has become the world's leading experts on the mysterious sanctuary on the magical Greek island of Samothrace

Michael Page

Over the course of a millennium, spanning from the seventh century BC to the fourth century AD, would-be initiates of the Mystery Cult of the Megaloi Theoi, the Great Gods, braved a difficult pilgrimage to the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace, a tiny island that rises up out of the Northern Aegean Sea like a beacon.

From out at sea, the pilgrims could glimpse the great buildings clustered in the valley and ridges that defined the sanctuary, but once they landed on the rugged island’s northern shore, its most sacred buildings were shielded from sight.

Up through the ancient city and out its southern gate, the devout would then descend along the Sacred Way to the Propylon of Ptolemy II—the monumental entryway perched on the sanctuary’s highest point—climbing the steps to the imposing marble building that was the portal to the mysteries within. When night fell, they would enter a narrow passage into the sanctuary, their path illuminated by the flicker of lamps and torches, to undergo closely guarded rites that would initiate them into an enviable circle of privilege and protection.

Very little was ever written about the cult—one of its inviolable rules was a vow of secrecy about its rites—and the mystery that surrounds it has yet to be fully solved, although excavation and study has been performed at the site since the fifteenth century.

Considered one of the world’s foremost experts on the site, Emory art historian and archaeologist Bonna Wescoat has spent her career discovering and deciphering the fragments of what, she says, was once one of “the most unique architectural collections of the Hellenistic Mediterranean in one concentrated place.”

In 2015, Wescoat and her team received three grants—from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the National Geographic Society, and the Partner University Fund—supporting work that will expand electronic access to the latest research and information on the sanctuary and the cult, further explore the unique range of architectural styles found in the sanctuary, and illuminate the area of the sanctuary that yielded the most celebrated artifact ever found at the site—the Winged Victory of Samothrace, or the Nike.

Discovered by a French expedition to the site in 1863, it was the Nike—or at least, the story of the discovery of her right hand—that first ignited Wescoat’s enthusiasm. As an undergraduate student at Smith College, she heard Phyllis Williams Lehmann, a renowned American archaeologist, lecture on the electrifying discovery of the missing hand in 1950.

Captivated by the story, Wescoat mustered the courage to ask the formidable Lehmann for a chance to work on an expedition to the island, but the opportunity was then open only to graduate students. It wasn’t until the following year, in 1977, that Wescoat would get her chance to visit the site after finishing a year at the University of London’s Institute of Archaeology on a Marshall Scholarship.

“I’d never been to Greece; I’d never done anything like this. Fortunately, it was not an excavating year, and I was allowed to go and help for a month,” Wescoat says.

Although exciting, that first journey to the island was anything but smooth. When Wescoat arrived in the Greek port town of Alexandropoulos, there was no place for her to stay overnight; the town was filled with military troops due to the ongoing dispute with Turkey over the sovereignty of the island of Cyprus. A kind hotel owner allowed her to sleep in his office, but she was plagued by mosquitos in the swampy climate and was unable to sleep. Finally able to drift off in the small hours of the morning, she nearly overslept and had to run to catch the morning boat to Samothrace. Once aboard, she climbed into a lifeboat and fell asleep on the then-three-hour trip to the island.

Upon awakening, she saw dolphins swimming alongside the boat, leaping out of the water, and then the island—only fifteen miles long, but more than a mile high—appeared “like a huge fulcrum rising out of the sea.”

“The island has a magical quality,” says Wescoat, the memory so powerful that tears come to her eyes even decades later. “This is why pilgrimage is so fascinating; it is one of the most extraordinary human experiences to travel to significant places vested in meaning.”

She spent three summers at the site as an archaeological assistant before joining Emory’s faculty as an assistant professor of Greek art and archaeology in 1982. From 1983 until 1988, she performed archaeological field research on the monuments of the western hill, and she has spent nearly every summer since 1997 on the island.

Since 2008, Wescoat has led an interdisciplinary team of Emory experts to build on the products of centuries of scrutiny—and her own decades of work—to create a better understanding of the ancient site and the rituals performed there.Wescoat says it was Emory’s support, through a Collaborative Research in the Humanities grant that year from the Office of the Provost that allowed her to pull together the team from departments across campus.

“That was the turning point because it gave us a leg up, at an early moment in digital technology, when we could become leaders in that field,” Wescoat says. “We now have a fabulous team of senior scholars and up-and-coming dynamic young professionals who bring new ideas. And, of course, the lifeblood of the project is the students; it is pure pleasure to watch their understanding and appreciation transform over the course of the season. It is exciting to work with all of the intellectual energy of multiple fields and multiple generations; that makes things come alive.”

In 2012, Wescoat was named director of excavations at Samothrace, succeeding James R. McCredie, professor emeritus at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, who had held the title since 1962.

“In that fifty years of work, Jim McCredie expanded our understanding of the site and doubled the number of buildings we knew of. Our primary purpose now is to understand what we have,” Wescoat says. “We are [digitally] reconstructing buildings to understand the geology and the chronology of the development, and to figure out what happened here through archaeological means rather than through what ancient authors have said, or not said, about the site.”

Wescoat received a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship in 2014 to support completion of a book, The Island of Great Gods: Samothrace and Its Sanctuary, which will focus on “the dynamic interaction of place and cult, and situating it within the broader context of religious experience, political dynamics, architectural developments, and social history of the eastern Mediterranean, from the first evidence of cult activity in the seventh century BC through the Roman period.”

Reconstructing The Sanctuary

In the first century AD, the Greek historian Diodorus of Sicily wrote in the Library of History of the powerful draw of the cult and the sanctuary where its closely guarded rites were performed.

“Fame has traveled wide of how these gods appear to mankind and bring unexpected aid to those initiates of theirs who call upon them in the midst of perils. The claim is also made that men who have taken part in the mysteries become more pious and more just and better in every respect than they were before.”

Wescoat says the work of digitally resurrecting the archaeological remains of the sanctuary may not reveal the full mysteries of the cult, but may lead to deeper understanding of how the configuration of sacred buildings, architecture, and decoration helped consecrate initiates’ experiences.

The grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, called “From the Vantage of the Victory,” will support the deep investigation of the region of the sanctuary where the Winged Victory originally stood. This area, which included the theater and stoa—a covered walkway used for gatherings—as well as other major votive monuments, was the celebratory heart of the sanctuary.

“We are drilling into its archaeological and environmental configuration and focusing on how its particular constellation of monuments and buildings came into being,” Wescoat explains. “Through this research, we hope to resolve some puzzles, including the design of the precinct that originally enshrined the Winged Victory.”

The location of the Victory is puzzling to Wescoat and other archaeologists because of its positioning in the sanctuary, in a small niche carved out of the hillside at the peak of the theater at the sanctuary’s southernmost point. It is unclear, both from the archaeological remains at the site and the condition of the sculpture, whether it was openly displayed or sheltered within its own enclosure.

The National Geographic Society (NGS) grant emerged after National Geographic magazine approached Wescoat about a major article and exhibition on ancient Greek religion, planned for June 2016. The article will focus on mystery cults and the quest for a better life, in this world and hereafter, so the Sanctuary of the Great Gods is an ideal subject.

“Apparently the magazine could not achieve the photographic imagery they wanted, so they asked if they could use our model,” Wescoat says.

Created in 2011, the 3-D, animated model of the sanctuary highlights the path of the pilgrim based on the digital reconstructions of the site’s architectural features, but more recent discoveries and advances in technology have rendered the model out of date. The NGS grant is allowing the team to expand and update the animations with a more naturalistic landscape around the architectural features, including vegetation and geographic features, and adding hardscaping such as distinguishing walls, pathways, roads, and other details that defined the site.

The new animation also will take viewers inside several of the buildings in the sanctuary that are unique to the site to capture the sense of space and ornamentation. “We are pretty secure in knowing what these buildings looked like and when they were built. What is harder to understand is their function,” Wescoat says.

Using what she calls a “phenomenological approach,” the team is following the path of initiates would have taken through the site to better understand the chronology of its development. “These are very powerful components of place and pathway,” Wescoat says. “We are recreating the momentum that built as initiates entered the sanctuary and the sense of going into the Earth that they likely felt as they descended the hill into the main area. We are using the power of the place to explain certain aspects of the cult.”

Rock Stars

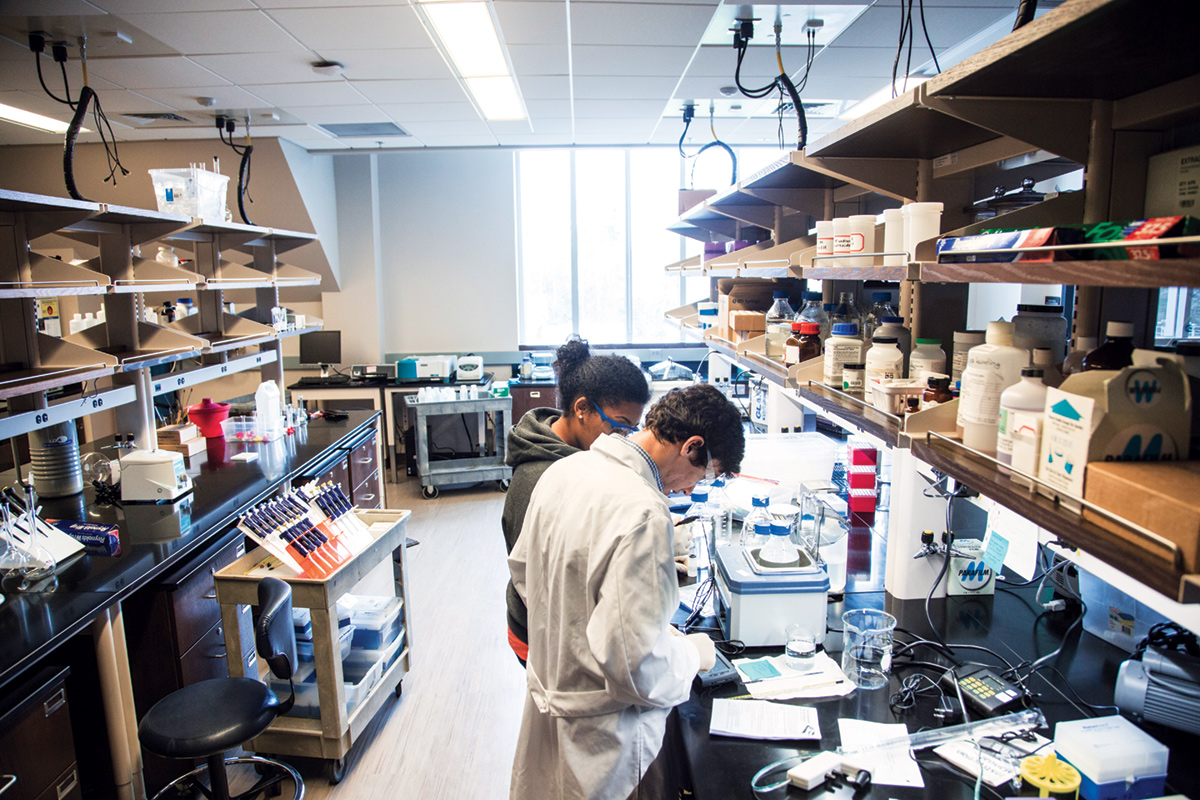

Interested in how the unusual topography of the site contributed to the experience of initiates, Wescoat enlisted Michael Page, an expert in geospatial sciences and technology, geographer, and cartographer who holds a dual appointment in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences and the Center for Digital Scholarship at the Woodruff Library.

Beginning in 2009, Page began a highly detailed topographic survey of the sanctuary and its surroundings to compare to older surveys performed by American, French, and Czech teams, the oldest dating back to 1867. Using robotic mounts, the team also has taken geo-referenced photographic surveys at Samothrace to inform the topographic survey, add to the historical record, and create web content for education. Last summer, Page took a drone to the site to perform flyover photography of the site.

“Just the sanctuary encompasses a valley incised into an alluvial fan and cut through by three ravines. It makes for a really unique landscape with a lot of complexities,” says Page, who along with the team has used detailed mapping to create the CAD models that are the basis for the 3-D animations. Page’s work is an essential part of the reconstruction efforts because the island is geologically volatile and subject to earthquakes, landslides, and flooding that have altered the landscape over the centuries.

“That is where geomorphology comes in, to examine what physical processes have been happening over time to change the landscape,” Page says. “We can see how it exists now and create a restored version of how it may have looked when it was in use.”

Emory geologist William Size has identified a wide variety of rock types used in the sanctuary, and has worked with the archaeological team to create color-coded plans identifying the types of stone used in the foundation of nearly every building in the sanctuary.

“It was amazing to me that they would use all of these types of rocks, but then I realized they used each type for specific purposes. Some were structurally strong rocks that could hold a lot of weight; while others were more ornamental and could be carved, or had color elements; and still others, used for pavement, had to be non-slip,” Size says. “It seems the ancient Greeks knew a lot about rocks and were quite smart about how they used them.”

On his most recent visit to the island, Size was able to collect samples of rocks from the sanctuary to bring back to Emory for testing. Aside from the marbles used in the sanctuary, which were shipped from nearby islands and the mainland, all the rocks used on the site are native to the island. Size has identified four scattered quarries on the island where stone may have been extracted.

Step By Step

Using data collected at the site, Vicki Hertzberg, associate professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, has worked on the metrology—the study of measurements— of the site. Because units of measure were not standardized before the Roman Empire, “There is controversy within the Greek archaeological community as to what the standard foot unit of measurement is, so the team thought Samothrace would be an excellent site to test the hypothesis,” Hertzberg says.

By examining measurements collected on the sanctuary buildings, their approximate construction dates, and the origin of the materials used, Hertzberg is analyzing both the “macro scale” measurements of the site—including building footprints and the distance along walls and between columns—and “micro scale” measurements—such as the size of the notches on columns and the distinguishing characteristics of individual building stones—to try to determine how a standard unit of measure was defined in antiquity.

The team hopes the analysis of the data from Samothrace will help determine whether foot-unit measurements were set by the masons at the quarries the stones were sourced from, or if, as some theorize, there were common standards of measure.

Spreading The Word

Another focus of the project is to provide wider access to the site for scholars and the public. In addition to a comprehensive website on the team’s work, Elizabeth Hornor, the Marguerite Colville Ingram Director of Education at Emory’s Michael C. Carlos Museum, has helped develop the pilot program for communicating and contextualizing this work through a virtual exhibition and blog.

“The goal is really to bring this magnificent place alive on a range of levels,” Wescoat says, “to understand what happened on this sacred island and why it was important then and is important now.”