Small Consolation

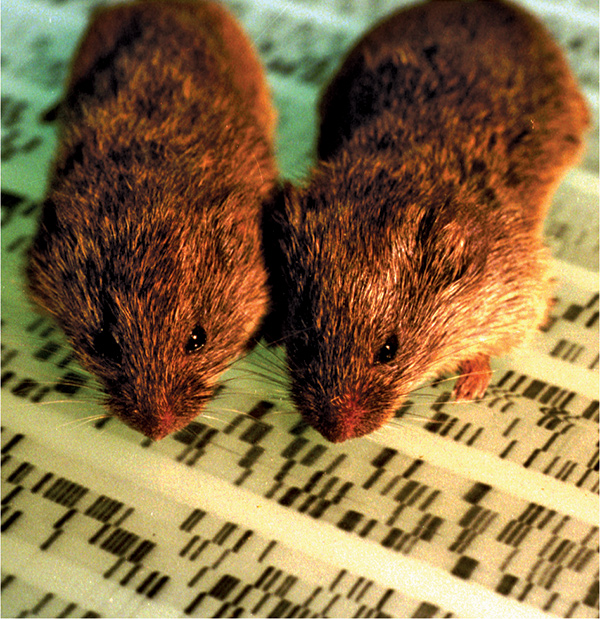

Breakthrough study finds that voles can show empathy

Researchers at Emory's Yerkes National Primate Research Center have discovered that prairie voles show an empathy-based consoling response when other voles are distressed.

This is the first time researchers have shown consolation behavior in social laboratory rodents, and the discovery ends the long-standing belief that detecting the distress of others and acting to relieve that stress is uniquely human.

The finding also has important implications for understanding and treating psychiatric disorders in which detecting and responding to the emotions of others can be disrupted, including autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia.

In the study, published in Science in January, coauthors Larry Young, division chief of Behavioral Neuroscience and Psychiatric Disorders at Yerkes, and neuroscientist James Burkett 15PhD demonstrated that oxytocin—a brain chemical well-known for maternal nurturing and social bonding—acts in a specific brain region of prairie voles, the same as in humans, to promote consoling behavior, specifically grooming. Prairie voles are small rodents known for forming lifelong, monogamous bonds and providing biparental care of their young.

Study coauthor Frans de Waal, director of the Living Links Center at Yerkes and professor of primate behavior in the Department of Psychology, says the recent vole study has significant implications by confirming the empathic nature of the consolation response.

“Scientists have been reluctant to attribute empathy to animals, often assuming selfish motives. These explanations have never worked well for consolation behavior, however, which is why this study is so important,” says de Waal.

Young, director of the Silvio O. Conte Center for Oxytocin and Social Cognition at Emory and a professor in the School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, says the research findings place greater emphasis on research into the brain systems underlying empathy.

“Many complex human traits have their roots in fundamental brain processes that are shared among many other species,” says Young. “We now have the opportunity to explore in detail the neural mechanisms underlying empathetic responses in a laboratory rodent, with clear implications for humans.”