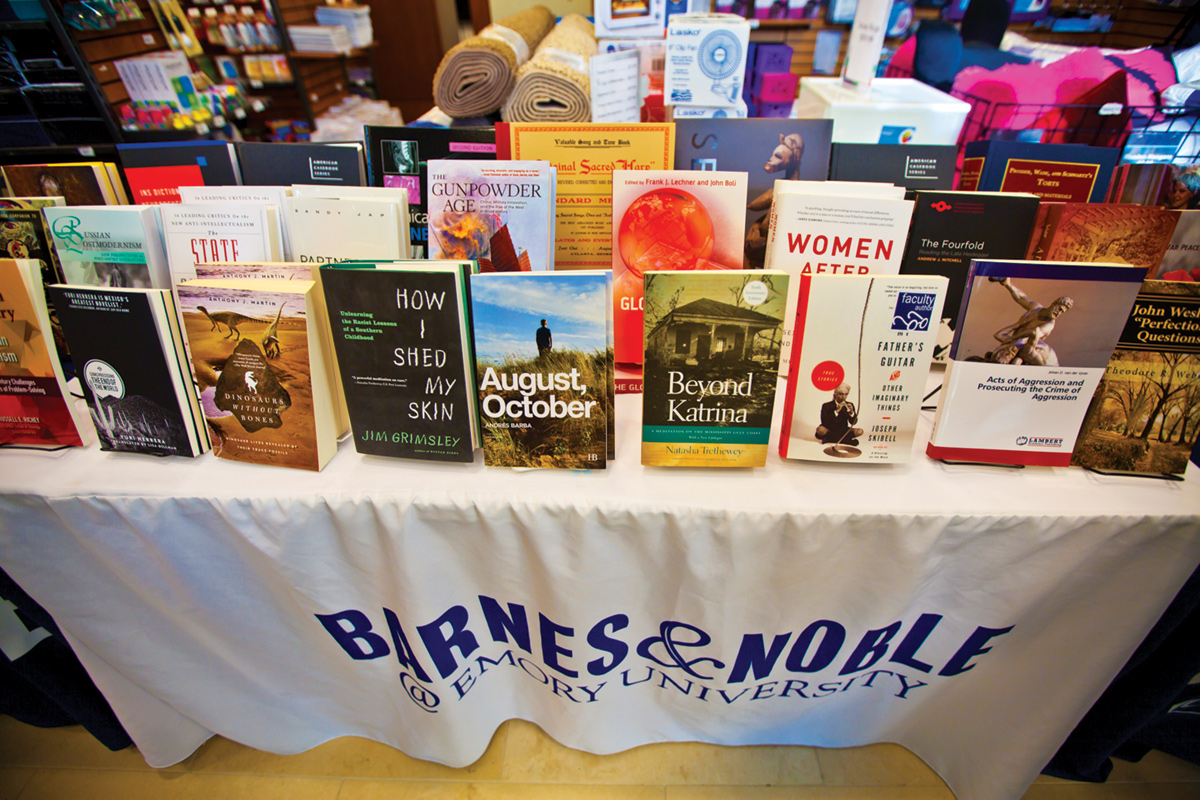

Looking for a Good Book?

Emory faculty published 123 last year

Celebrating a year's worth of faculty publishing never fails to produce remarkable evidence of compelling original thought and research, as well as breadth of subject matter.

Here we offer a sampling; find the full list of titles at the Center for Faculty Development and Excellence.

Two many

Assistant professor of religion James Bourk Hoesterey, author of Rebranding Islam: Piety, Prosperity, and a Self-Help Guru, spent two years shadowing the charismatic Indonesian television preacher known to a nation of admirers as Aa Gym.

With a self-help message of "Manajemen Qolbu" ("Managing the Heart"), Gym transformed himself from a young man without formal religious education into a religious celebrity, national icon, and Islamic brand. Viewers by the millions watched his weekly television shows, hundreds of thousands made pilgrimages to his Islamic school, and politicians of all stripes sought photo-ops during campaign season.

When Gym's devoted public discovered that he embraced polygamy—legal in Indonesia—by taking a second wife, it all came crashing down. Women shredded his picture, the country's president ordered a review of marriage law, and Gym's business empire dissolved.

In the end, Hoesterey concludes, religious figures who follow will not equal Gym's celebrity because it was achieved during the uncertain, yet hopeful, dawn of post-authoritarian Indonesia.

Think different

Nothing sparks more thought about thought than encountering a mind different from one's own," writes Laura Otis, a former MacArthur Fellow and now professor of English, in Rethinking Thought: Inside the Minds of Creative Scientists and Artists.

Until recently, scientists' search for similarities guided studies of the human brain. Examining "individual quirks," Otis says, "has been a luxury that they cannot yet afford."

Otis builds a fascinating narrative around, as she calls them, "thirty-four different heads." They include those who work in science or literature or (like Otis) some combination thereof. Some of those she interviewed are well known to the Emory community: Mark Bauerlein, Natasha Trethewey, and Salman Rushdie.

If you join Otis on this journey, don't pack any preconceptions about how people think. Those are in somebody else's book. Her message is that minds must be able to present their strengths variously and without limits.

In the end, you will grow to appreciate the quirks and smarts of the thirty-fifth head—that of the author herself.

Sacred Roots

For the uninitiated, an NPR feature described the paradox of sacred harp singing: "There's no harp in sacred harp singing—no instruments at all. Just the power of voice, in four-part harmony. The origin of the music goes back centuries—first in England, then in colonial New England, then the music migrated south, where it took root."

Jesse Karlsberg, Woodruff Fellow and doctoral candidate in the Institute of the Liberal Arts, is the prime mover behind Original Sacred Harp: Centennial Edition. It is a commemorative, facsimile, reprint edition of the 1911 edition of Original Sacred Harp, which has helped to maintain the music and practice up to the present. This meticulously digitized and restored copy represents a collaboration among Pitts Theology Library, the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, Woodruff Library, and the Sacred Harp Publishing Company.

Karlsberg says he chose to edit a facsimile reprint rather than re-typeset because the original "quirks, typographical errors, and uneven print quality . . . speak to its historical circumstances."

Beastly, but in a good way

Surely when praise from Jane Goodall—the United Nations Messenger of Peace—adorns your book's back cover, you have done something right. The book is Beastly Morality: Animals as Ethical Agents, and the editor is Jonathan Crane, Raymond F. Schinazi Scholar in Bio-ethics and Jewish Thought at the Center for Ethics.

The volume has sparked a paradigm shift in animal studies by envisioning nonhuman animals as distinct moral agents. Crane points out that "animal welfare, while revolutionary in many aspects, nonetheless maintains its ultimate gaze on the human animal, not the nonhuman animal." Drawing on ethics, philosophy, law, ethology, and cognitive science, contributors argue that nonhuman animals possess complex reasoning capacities, empathic sociality, and dynamic self-conceptions.—Susan Carini 04G