Responding to Zika Virus

Experts say mosquito control is key to curbing the latest viral outbreak

While health officials monitor the spread of Zika virus from areas of outbreak in Latin America and the Caribbean into the US and abroad, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued a health advisory that sexual transmission of the virus may be more common than previously thought.

The Zika virus, unlike other mosquito-borne viruses, was relatively unknown and unstudied until it was recently associated with an alarming rise in babies born in Brazil with abnormally small heads and brain defects—a condition called microcephaly.

“The microcephaly cases are a personal tragedy for the families whose babies are affected. They will need much care and support, some of them for decades. The costs to the public health system will be enormous,” says Emory's Uriel Kitron, an expert in vector-borne diseases, which are transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, or other organisms.

For the past several years, Kitron has collaborated with Brazilian scientists and health officials to study the dengue virus, which is spread by the same mosquito species, Aedes aegypti, as Zika. The focus of that collaboration is now shifting to Zika.

“Zika is a game-changer. It appears that this virus may pass through a woman’s placenta and impact her unborn child. That’s about as scary as it gets," says Kitron, who traveled to Brazil to support the country’s research strategies and control efforts for the outbreak.

Now the CDC and state public health departments in the US are investigating a number of reports of possible sexual transmission of the virus from men who had been infected to their partners. Zika virus has been found in body fluids including blood, urine, saliva, and semen, and remains in semen even after it has been shed from the blood, according to the CDC. It is unknown how long the virus remains in semen.

Since the Zika outbreak began in northeastern Brazil last spring, an estimated five hundred thousand to 1.5 million people have been infected. The resulting illness—whose symptoms include a rash, joint pains, inflammation of the eyes, and fever— only lasts a few days. As many as 80 percent of infected people may be asymptomatic.

It was not until months after Zika cases showed up in Brazil that a spike in microcephaly births was tied to women infected during pregnancy. More than 3,500 microcephaly cases have been reported since October in Brazil, compared to 150 in 2014.

Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec is an Emory disease ecologist who specializes in spatial analysis of the movement of people, mosquitos, and pathogens in order to zero in on transmission patterns of epidemics. He describes Aedes aegypti as the roaches of the mosquito world, perfectly adapted to living with humans, especially in urban environments. “Now we have three viruses—dengue, chikungunya, and Zika—being spread by Aedes aegypti,” says Vazquez-Prokopec, “so that greatly increases the cost-effectiveness of doing high-quality, thorough mosquito control.”

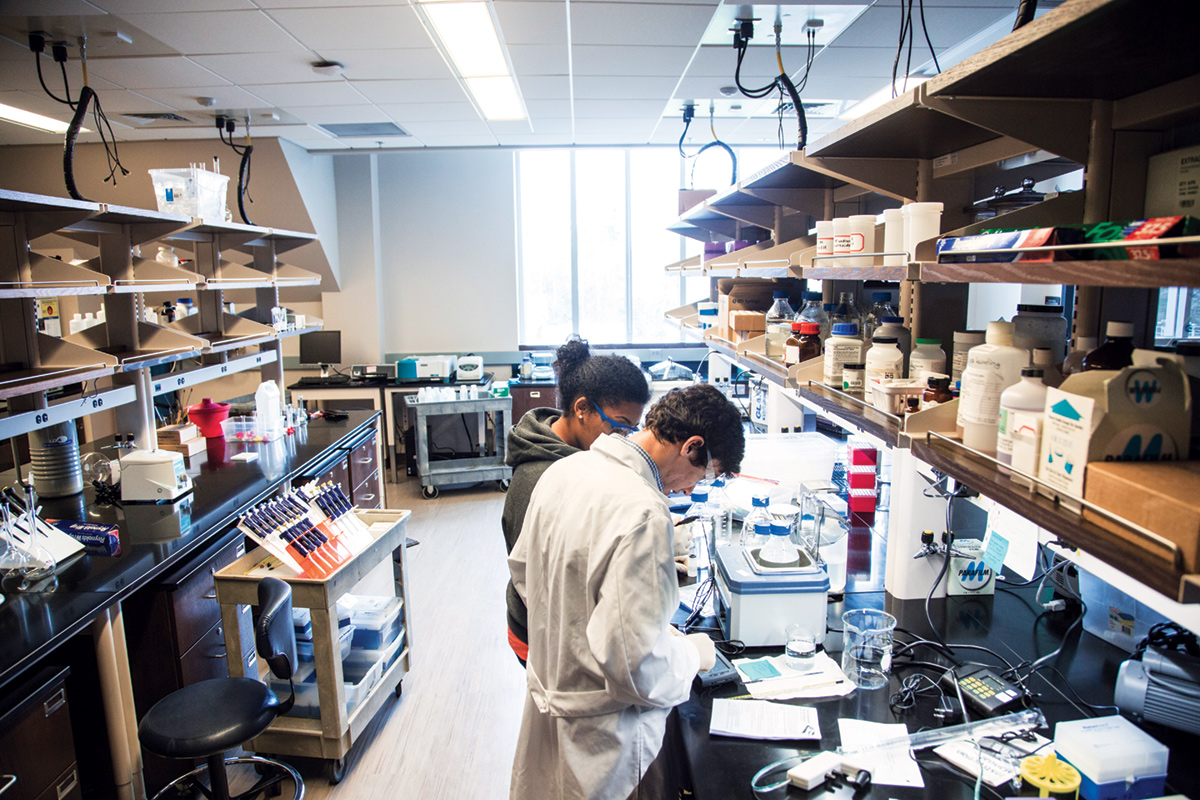

Drug Innovation Ventures at Emory (DRIVE) and the Emory Institute for Drug Development (EIDD) have launched an effort to identify and develop antivirals to treat the infection caused by Zika virus. "Since Zika is a flavivirus in the same family as dengue and hepatitis C, we can apply what we have learned working on alphaviruses and flaviviruses, as well as from our past success with treatments for HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and herpes viruses, in our search for an effective drug,” says George Painter, CEO of DRIVE and director of EIDD.