Scalia More Quotable than Influential

Justice Antonin Scalia will be remembered for his brilliant intellect, his acerbic wit, and his insistence on interpreting law by reference to text and history. He was long the intellectual leader of the conservative wing of the United States Supreme Court. However, he often seemed more interested in being a leader than in having followers, at least on the Court.

As someone who had the privilege of clerking on the Supreme Court for Justice John Paul Stevens during Justice Scalia’s tenure, I will continue to enjoy my memories of Justice Scalia’s dynamic interaction with clerks. As a professor of constitutional law, I will continue to study and to teach Justice Scalia’s incisive opinions. When it comes to learning how courts actually interpret the law, though, the majority opinions on which my class focuses are unlikely to be written by Justice Scalia.

He was appointed to the court by President Ronald Reagan in 1986 at a pivotal time for the conservative movement, which sought to undo prior liberal decisions and to limit the power of the national government by rigorously scrutinizing federal statutes. Justice Scalia served as a perfect champion of these new conservative ideals. He embraced “originalism,” the idea that insists that the Constitution must be interpreted by reference to its meaning at the time of its adoption. This approach rejects the idea that new rights may emerge over time.

He also endorsed textualism, which interprets statutes by focusing solely on their language, rather than the legislature’s overall purpose in enacting them. By refusing to attend to the purpose of legislation, textualism imposes a substantial burden on the legislature to draft complex statutes with exacting precision.

These interpretive swords of originalism and textualism allowed Justice Scalia both to attack liberal precedents that had strayed from what he understood as the Constitution’s historic meaning and to limit the scope of governmental power.

Singlehandedly, he changed the way in which statutes were discussed in the Supreme Court. Beginning in the 1990s, a new conservative majority limited the power of the national government, striking down or narrowing important federal legislation such as the Violence Against Women Act, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, and the Voting Rights Act.

But Scalia’s victories were limited. His style did not always ingratiate him with potential allies on the court. He did not mince words, and he attacked the opinions of other justices, liberal and conservative, with unusual ferocity.

In Webster v. Reproductive Health Services in 1989, Justice Scalia famously attacked Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s reasoning in an important abortion case. Three years later, he ended up on the losing side of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, as Justice O’Connor coauthored an opinion for a five-justice majority reaffirming the right to an abortion.

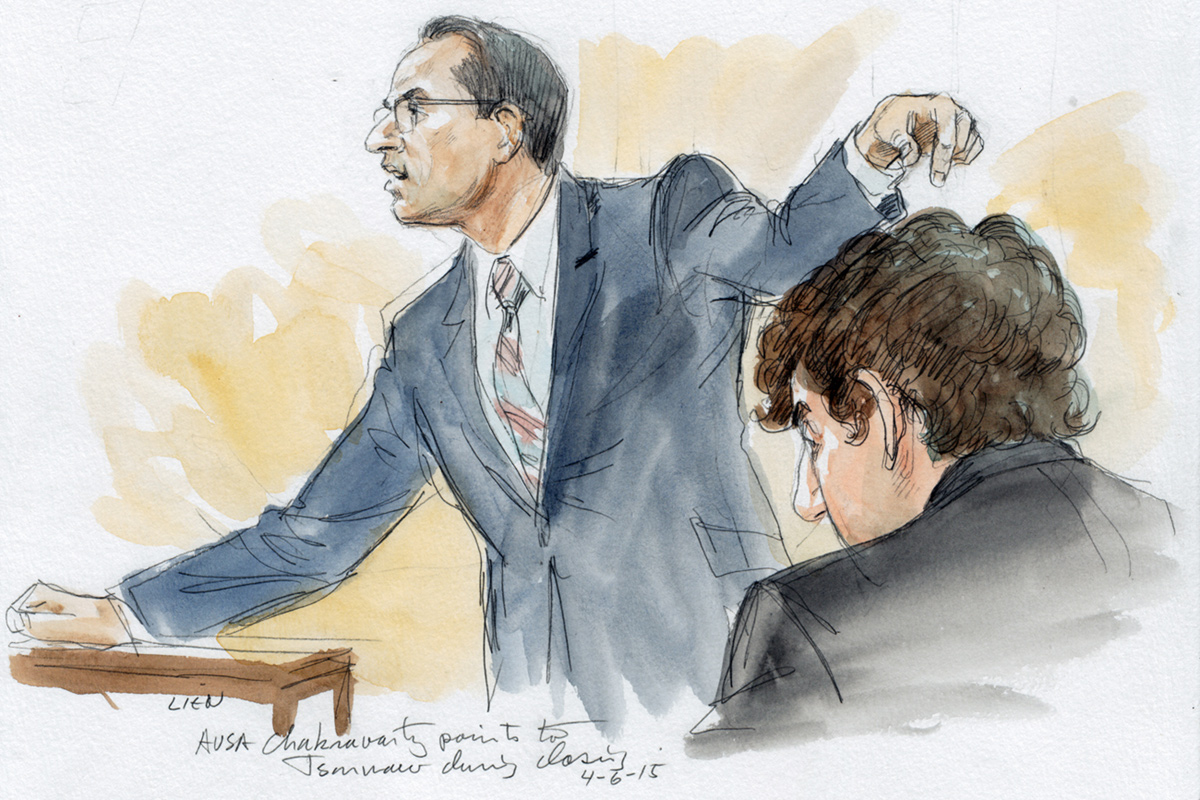

In 2015, finding himself in dissent in the year’s most significant cases, Justice Scalia’s vitriol reached new heights. While his caustic style may have been off-putting to some justices, what was more significant was that his interpretive approach failed to win over his colleagues.

In King v. Burwell, a strict reading of the text of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would seem to have authorized federal subsidies only for health care exchanges established by states, not for those established by the federal government in states that refused to create exchanges.

If textualism had prevailed, the scope of federal power would have been limited, in this case by potentially gutting the ACA. But Chief Justice Roberts instead applied traditional principles of statutory interpretation and looked to the overall purpose of the legislative scheme. Scalia’s textualism lost; the ACA won.

Justice Scalia’s focus on beginning any interpretation with the text of a statute may endure, but his rejection of other interpretive guides never found a lasting home on the court. His attempt to reorient interpretation of the Constitution similarly failed to achieve lasting success. Obergefell v. Hodges, for example, the case affirming a right to same-sex marriage, constituted a dramatic repudiation of Justice Scalia’s originalism. For Justice Scalia, the disposition was easy: “When the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, every state limited marriage to one man and one woman, and no one doubted the constitutionality of doing so. That resolves these cases.”

Contrary to Justice Scalia’s originalism, Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion understood the Constitution as entrusting to “future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.” The idea of a “living Constitution,” always anathema to Justice Scalia, prevailed.

Justice Scalia’s opinions, full of erudition, wit, and occasional vitriol, will long be quoted and will fill the pages of legal textbooks. But the memorable opinions will largely be dissents. He was the champion of a movement that achieved many of its goals but did not succeed in fundamentally reshaping the law in the United States. He will go down in history, in my view, as one of the most quotable justices, but not one with the deepest impact.

Robert A. Schapiro is dean of the School of Law and Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law. This article was originally published on The Conversation. This version has been edited for length.

Email the Editor