Positive Potential

New Oxford building lets science shine

It's a drizzly Monday morning in early January—a sure formula for sleepy students at Emory's Oxford College campus.

But there’s no way Associate Professor Frosso Seitaridou is letting her Physics 152 class get off that easy. Petite and energetic, with a lilting Greek accent, Seitaridou beams at the students like the sun itself, shooting pointed rays in all directions. This morning’s lecture is on electrostatics, and Seitaridou is covering the multi-paneled white board with complex formulas. “Isn’t that beautiful?” she asks, insistently, drawing appreciative nods. “I find electrostatics really beautiful. I hope that this semester we can all hold hands and cry together at how beautiful and elegant this is.”

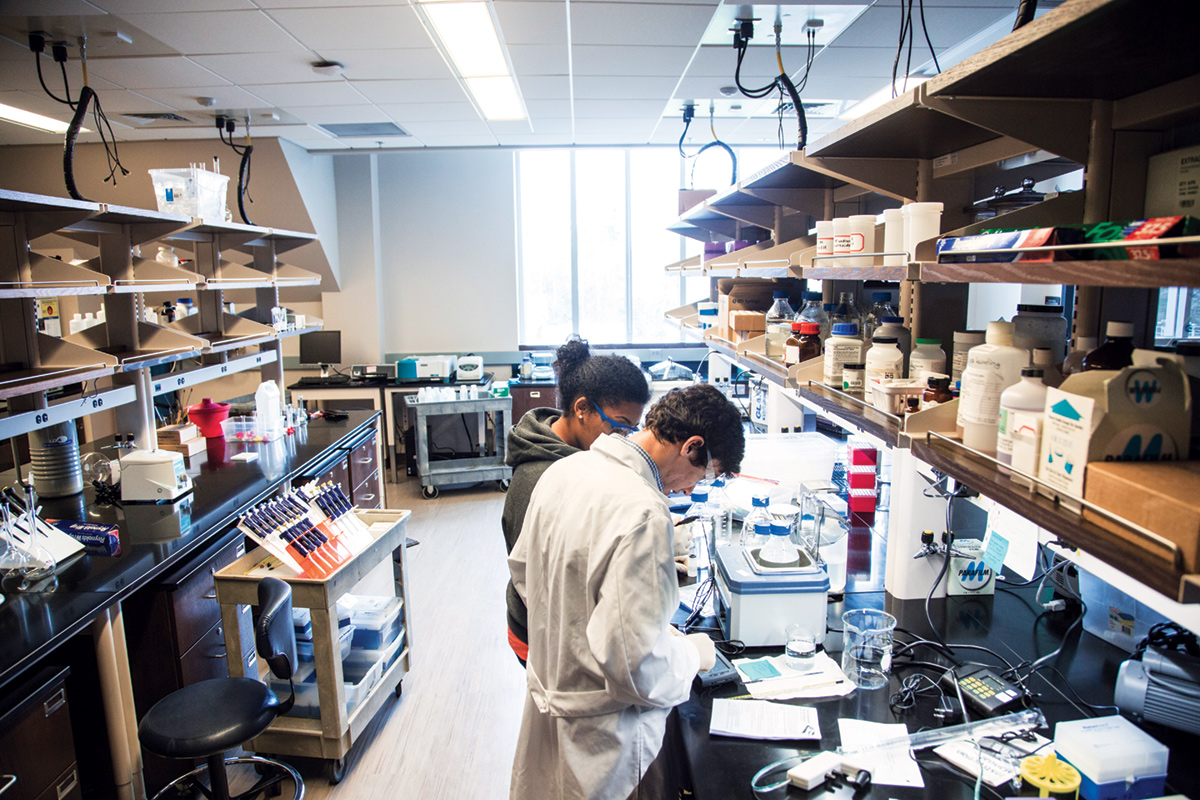

Seitaridou’s enthusiasm for the beauty and elegance of electrostatics is reflected and amplified by her surroundings. Room 217 of the brand-new Oxford Science Building is spacious and state-of-the-art, with gleaming fixtures, butcher-block lab tabletops, and bright, contemporary lighting. It’s impossible not to sense the undercurrent of excitement that permeates this eagerly anticipated learning space.

Emory’s original campus, home to some nine hundred freshmen and sophomores, has long been known for its attentive, hands-on approach to undergraduate education. Driven by the high standards of a dedicated, demanding, and ever-inquisitive faculty, science instruction has been a point of particular pride, with a focus on experiential learning both in the lab and in the field. For many who know Oxford, the new building represents not a transformation of science education so much as a physical manifestation of the academic rigor that already fueled the core of the program.

“The Oxford Science Building is the latest and most dramatic accomplishment in the decade-long effort to create a campus learning environment equal to the quality of Oxford’s educational program,” says Dean Stephen Bowen. “Never was there a building more thoughtfully planned to support hands-on, inquiry-driven undergraduate science education. The building is in itself an expression of the Oxford culture.”

At fifty-seven thousand square feet, the science building is the largest on the Oxford campus, with nine labs total, six lab prep areas, three cross-disciplinary research laboratories, a greenhouse, an outdoor classroom, and multiple spaces created for group collaboration—whether planned or spontaneous. It was designed by EYP Architecture and Engineering, a national firm known for building projects that both achieve objectives and fit authentically into their surroundings. Architects planned the Oxford Science Building around a theme of “kinship”—between students and faculty, the campus and the natural world, and the Oxford community past, present, and future. Although modern, stylish, and technically equipped to the latest standards, the structure has many thoughtful architectural details that pay homage to the design influences visible in Oxford’s other buildings.

“Oxford has always been hardwired for science as part of the liberal arts—a preprofessional campus where doctors, nurses, and scientists got their start—even though our science facility has operated at a disadvantage for decades,” says Joe Moon, dean of campus life. “The new building is going to be a quantum leap for us.”

Oxford alumni and friends, many of whom supported the fundraising efforts for the Oxford Science Building, share in the celebration. According to Bowen, more than 720 gifts allowed the building to be completed debt free and ahead of schedule in late 2015, and several are noted in the building’s named spaces.

Retired surgeon R. Trulock Dickson 72OX 74C gave to the building in honor of retired faculty member Homer F. Sharp Jr. 56OX 59C. “I wanted to name the whole building after him if I could, because he has influenced thousands of Oxford students,” Dickson says. “This is going to make science even stronger at Oxford.”

Chris Arrendale 99OX 01C volunteers his time as president of the Oxford Alumni Board; he and his wife, Amanda, also made a gift. “We want to make the future even better for Oxford students than what we had,” Arrendale says. “This is a huge step forward that shows we are serious about having state-of-the-art facilities for science education.”

It is notable that Oxford’s science faculty also were actively engaged in the planning for the science building, helping to ensure that the finished product would genuinely serve the way they teach. Eloise Carter 78G 83PhD has taught biology at Oxford since 1988 and has helped to shape the experiential learning approach that has become a hallmark of science education at the school.

“The faculty members share two things in common,” Carter says. “One is the passion for science, even though we are not all researchers. We love the process of science and our own areas of inquiry. Second is we have a big, shared interest in challenging and supporting our students. We want them to think like scientists.”

That desire is palpable in Seitaridou’s physics class, where she continues to engage the students with relentless energy.

“No student of mine will not be able to explain positive potential,” she warns. “When you sleep, I should be able to come and wake you up and say, ‘What does positive potential mean?’ and you should be able to answer.” A couple of students shift nervously; it is easy to imagine that she might actually do it.

For Seitaridou, the Oxford Science Building is simply academic promise more fully realized, a richer and better appointed setting for her to inspire new generations of—who knows?— future physicists.

“Students are the first priority here, not the faculty,” she says. “It’s up to me to share with them my love of physics. Physics is complicated and difficult, but the rigor is not intimidating—it makes me hopeful because we are all capable of amazing things. We are all capable of understanding what is rigorous and developing the tools to understand the beauty of that rigor.”

That’s at least one definition of positive potential.