From the President

Lessons Unsought

One hallmark of Emory that I admired before interviewing for the job of being its president was the willingness, even eagerness, of this community to seize on "learning moments." Those are the unexpected and unpleasant episodes that force us to take stock of ourselves as a community, as an institution.

Every university experiences them. They can range from the disruptive and embarrassing, like the firing and then rehiring of the president of the University of Virginia last spring, to the truly horrific, like the criminal abuse perpetrated by a once-respected football coach at Penn State.

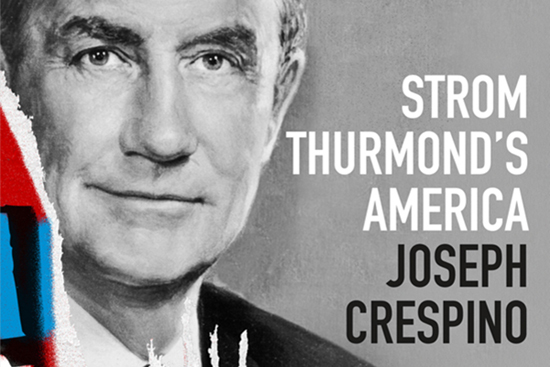

Over the years we at Emory have had our own share of "learning moments"—incidents that have caught us up short and prompted us to pause and make some adjustments before continuing on in our mission. When a regrettable racial incident nine years ago forced us to examine personal and institutional commitments to nondiscrimination, that moment of introspection led to the Transforming Community Project, which in turn had broad personal and institutional impact on our understanding of America's racial history and our own.

Similarly, two years ago, student protests over contract labor on campus led to very wide-ranging, thoughtful, and extended conversations that have grown to involve faculty, students, and staff members through the Committee on Class and Labor and the Task Force on Dissent, Protest, and Community. We are learning a lot about how we perceive each other and behave toward each other on the basis of our perceptions. I expect that we will gain from these conversations a deeper sense of community as well as a stronger commitment to what makes a university excellent.

We have experienced another learning moment since we discovered last spring that administrators responsible for representing Emory to the world through data were, for more than a decade, intentionally misreporting statistics that measure our success in admission. Those responsible are no longer at Emory. But for those of us who remain—including our devoted alumni and supporters around the world—the sense of loss has been great.

There are no doubt many lessons to be learned from this moment, but one in particular stands out for me. It is the old truth taught to us by the Greek tragedies. It is the reminder that our virtues can often be our undoing, that our focus on excellence can blind us. It is the lesson that an institution's place of strength can also be its blind spot, making it vulnerable to human error or misguided intentions. One of Emory's strengths—and hence a point of risk—may be our institutional language about ethics and integrity.

Martha Nussbaum, one of our 2011 honorary degree recipients, wrote a book about "the fragility of goodness." Delving into Greek philosophy, she underscores that reason, systems, careful discipline, and watchfulness can carry us only so far toward fulfillment of "the good life" that was so highly prized by the Greeks. Some degree of luck is also necessary. Goodness continually stands vulnerable to the "slings and arrows of outrageous fortune."

The integrity of an institution is equally fragile. It can be broken without warning, and once it is broken the repair work carries an enormous cost in terms of morale, pride, momentum, and trust.

Emory is especially vulnerable in matters of integrity, because we so baldly state our intention to strive to engage ethically. Emory traditionally has prided itself on education of the heart as well as the mind, a legacy of our Methodist founders. Their theology called them to be continually "going on to perfection." They fully understood that the aspiration for goodness is continually a work in progress. That work takes a step backward when aspiration for one kind of good—say, the good of claiming outstanding students—undermines an aspiration for a better kind of good—say, the institution's integrity and transparency.

I have no doubt that we have learned from this latest episode three further valuable lessons. The first is that we must have a process of data review that offers checks against misreporting. We now have that process in place.

The second lesson is that our vulnerability to fortune makes humility imperative. We do not need to give up our aspiration for excellence; we should recognize, though, how much it depends on good fortune as well as vigilance and talent.

Finally, we can learn to continue imbuing our community with the soundest ethical principles lived out through good practices, making the habit of integrity a daily part of our individual and communal life. The human condition might make the betrayal of trust inevitable, or at least unsurprising. But our regard for each other and our accountability to each other make it more difficult. The habit of caring about our own integrity and each other's can make the goodness of this place less fragile. That seems to me a lesson worth keeping, even if unasked for.