Works and Days

The road to northwestern Uganda's Moyo district continues up to the Sudanese border, and there's a reason why it's known as "the boneshaker." Wide, red, and deeply rutted from one side to the other, this road is what SUVs like Range Rovers and Land Cruisers were made for—despite their popularity on the paved streets of metro Atlanta, where they encounter the occasional pothole.

In Moyo's remote Liwa Village, Amandua Rashid lives in a Muslim community surrounded by fertile farmland. For three years he has worked as a volunteer community drug distributor for Uganda's national program to eliminate river blindness, a groundbreaking effort launched in partnership with The Carter Center.

In July, university photographer Kay Hinton and I visited Rashid's village and others like it, shadowing senior epidemiologist Moses Katabarwa 97MPH to report on the progress and challenges of the River Blindness Program. (That's me above, with the camera, and Moses standing on the right.)

Once a year, Rashid distributes the drug Mectizan to 111 people in thirty-four homes for the treatment and prevention of the disease, which causes severe itching, skin problems, and sometimes blindness. He said it is a good feeling to perform this service for his community, which takes him about three full days.

When we asked him what he does with the rest of his time, he shrugged shyly. "Nothing," he said. "Just farming."

Carter Center staff member Stella Agunyo laughed, protesting, "Farming is not nothing! There is a good living in farming!"

Perhaps what Rashid meant was that his occupation should have been fairly obvious. Most of the area is devoted to agriculture, as is much of Uganda, where the land and climate are well suited to growing things from corn to cows. It probably didn't occur to him to proclaim, "I am a farmer," when the day-to-day rhythm of his livelihood comes as naturally to him as breathing.

The question, "What do you do?" is a fairly common one for most of us in the US, at least in circles such as those that connect the broad Emory community. Many have a ready, straightforward answer; for others, their professional story is more complex.

Rashid's response, though, made me reconsider the question, which is kind of odd to begin with if you think about it. "What do you do?" places the emphasis on behavior and action rather than character and passion, as if people's external activity on any given day can effectively represent their engagement with their vocation. While there are undoubtedly those whose jobs are more chore than choice, it seems to me that most of us would strive for a more organic approach in which life and work are inseparable—woven so closely that, as for Rashid, profession and personal identity are one. With that as the ideal, it's possible that a better way of phrasing the question might be, "Who are you?"

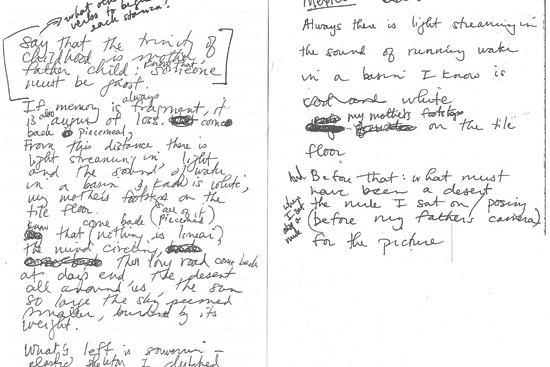

Our cover subject, Natasha Trethewey, has an answer both simple and profound: she is a poet. To be precise, she is the poet, the newest US poet laureate, an honor she told us she feels gives her "permission" to be the poet she is.

Professor Merle Black has a pretty straight answer, too. He's a political scientist, one of the best-known experts in the country, particularly when it comes to Southern politics. And Katabarwa is an epidemiologist and public health advocate whose work with The Carter Center and other organizations has advanced, in tangible ways, the progress against neglected tropical diseases.

Of course, no one featured in this or any issue of Emory Magazine can be reduced to a word or a title; their lives are richly layered and their identities multidimensional. But one thing these subjects have in common is that they have reached a point in their careers marked by accrued wisdom, concrete accomplishment, and sustained dedication. Driven by spirit and vision, they likely will never stop pursuing new challenges; but professionally speaking, they know who they are—and there is real power in that.

This fall, Emory welcomed a bright new class of freshmen, all of whom are setting out to find their own answers to the question of who they will be and how they will spend their days. Among them are future health experts, political scientists, poets, maybe even farmers. As is increasingly the norm, many will have multiple occupations as the landscape shifts around them, and they will no doubt experience the ebb and flow of success.

Whatever they may become, I offer them one of my favorite lines from the Desiderata: "Keep interested in your own career, however humble; it is a real possession in the changing fortunes of time."