Driving Back through Time

Lawrence Jackson makes a research project personal

If you go there, you who never was there—if you go there and stand in the place where it was, it will happen again; it will be there for you, waiting for you.

Kay Hinton

For his latest book, Professor Lawrence P. Jackson challenges himself to break with type in a couple of notable ways: first, he leaves the office and the library to chase down some clues to a family mystery from behind the wheel of his car—making a lot of wrong turns in the process. And second, he turns his scholar's inquisitiveness and research skills inward, applying them to his own life and family history.

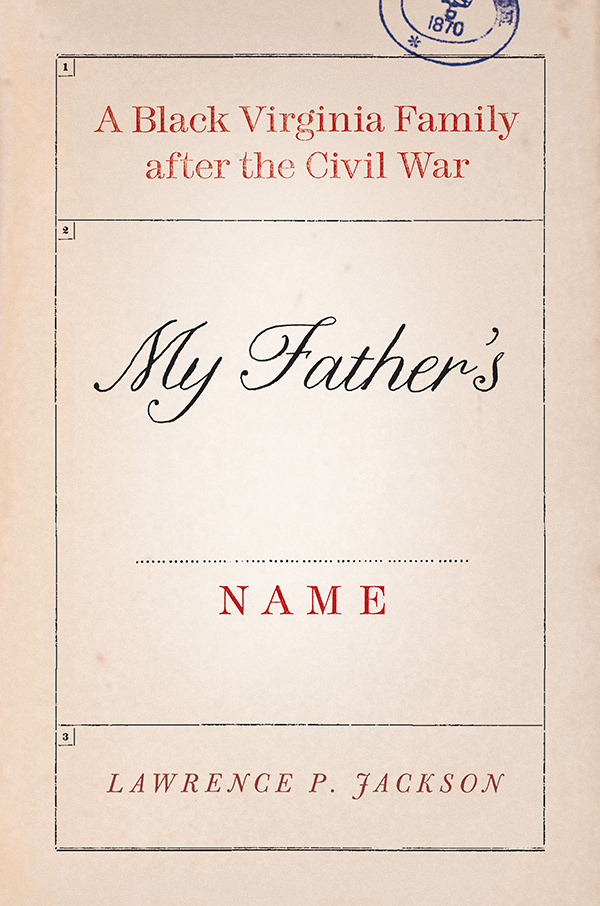

In My Father's Name: A Black Virginia Family after the Civil War, Jackson seeks greater knowledge of his father's family. What he finds astonishes and pains him, despite his well-tempered expectations of race relations in this country and mastery of African American history.

The journey began on his deceased father's birthday in 2001—the year before he joined Emory as professor of English and African American studies—when Jackson traveled to Danville, Virginia, the area where his family was from. Then in 2004, his curiosities still simmering and his first son Nathaniel (named for his father and grandfather) on the way, Jackson drove just north of Danville to the outlying town of Blairs, thinking that "walking the terrain of my forebears would put me in a paternal frame of mind and that, with luck, I might unearth my grandfather's house by the railroad tracks." He goes on, "I was curious about how my father's people saw the world. . . . I wanted to better understand my father, such a formidable presence in my own memory."

What started as a day's lark in 2001 became a meticulous search that didn't end until eleven years later with the publication of the book. In between, a lot of gravel is scattered in convenience store parking lots as Jackson continually reorients himself, geographically and emotionally, for the truth that lies ahead.

"What am I really looking for?," Jackson wonders, early on. "A house? A man? A family? A memory?" As he encounters a diverse cast of characters along the way, he must make a series of social negotiations, adding layers to his identity as quickly as he adds miles to his odometer.

Jackson traces his family's past—both across Virginia terrain and in various records offices—to ultimately discover that his great-great-grandfather, Granville Hundley, was either born a slave or sold into slavery by the 1840s. Similarly, his father's grandfather, Edward Jackson, likely spent 1855 to 1865 as another man's property.

That revelation is unnerving, despite the preparation of years as a historian. Jackson is unequivocal about the pain and degradation of slavery, calling it a "genocide involving tens of millions of people."

"What being a member of a powerless but highly visible minority group descended from ex-chattels means is to look at yourself, your past, through the myths, the joys, the guilt, and the fear of someone else," he says.

There are a thousand metaphorical miles between that moment and the assumptions that Jackson harbored as a younger man. In high school in Baltimore during the Reagan years, Jackson recalls, "The success of the civil rights movement, as I understood it then, was that my racial background would not hinder me if I lived an immaculate, cautious life."

Jackson's great-great-grandfather was able to purchase a forty-acre tract after his enslavement ended—land that was parceled out to six children and eventually lost. The physical search for it ends in late winter 2009, when Jackson stumbles upon a "compact graveyard" that was one of the concrete boundaries of Granville Hundley's 1877 tract.

Immediately adjacent is land formerly owned by a white doctor, Edward Williams, and his wife, who had imagined themselves as Napoleon and Josephine and named their residence Malmaison after Napoleon's residence. The current occupants of the house are the Chandlers, a white couple Jackson describes as "cheerful and gregarious. But our divergent paths spoke loudly. . . . In the hallway, they kept a bust of General Lee . . . and in the corner of the kitchen they had four ceramic figures, 'smiling darkies.' "

As a boy, Jackson used to chide his father for driving below the fifty-five-mile-per-hour speed limit on family trips. As a result of the journey he makes in the book, Jackson is rethinking the haste of his modern life.

"The rapid movement across space and time creates a mirage," he writes. "I am more interested in looking for myself by way of gathering these ancestors of mine; I want my travel to go in that direction."

Typically, his father wouldn't respond when an exasperated teenage Jackson cajoled him to go faster. Once, though, his father did answer, saying simply, "I like to look at the trees."

Lots of things, it turns out, can't be done in haste. And all of Jackson's wrong turns became chapters in a longer narrative about providing two sons a key to their past.