Setting the Record Straight

New oversight will ensure Emory's data integrity

In August, Emory released publicly the results of its three-month investigation into how admission-related data were misreported to external audiences, including standard reference sources that generate rankings, such as US News & World Report. The report indicated that the practice had been going on for more than a decade, although the investigation was unable to determine how it began.

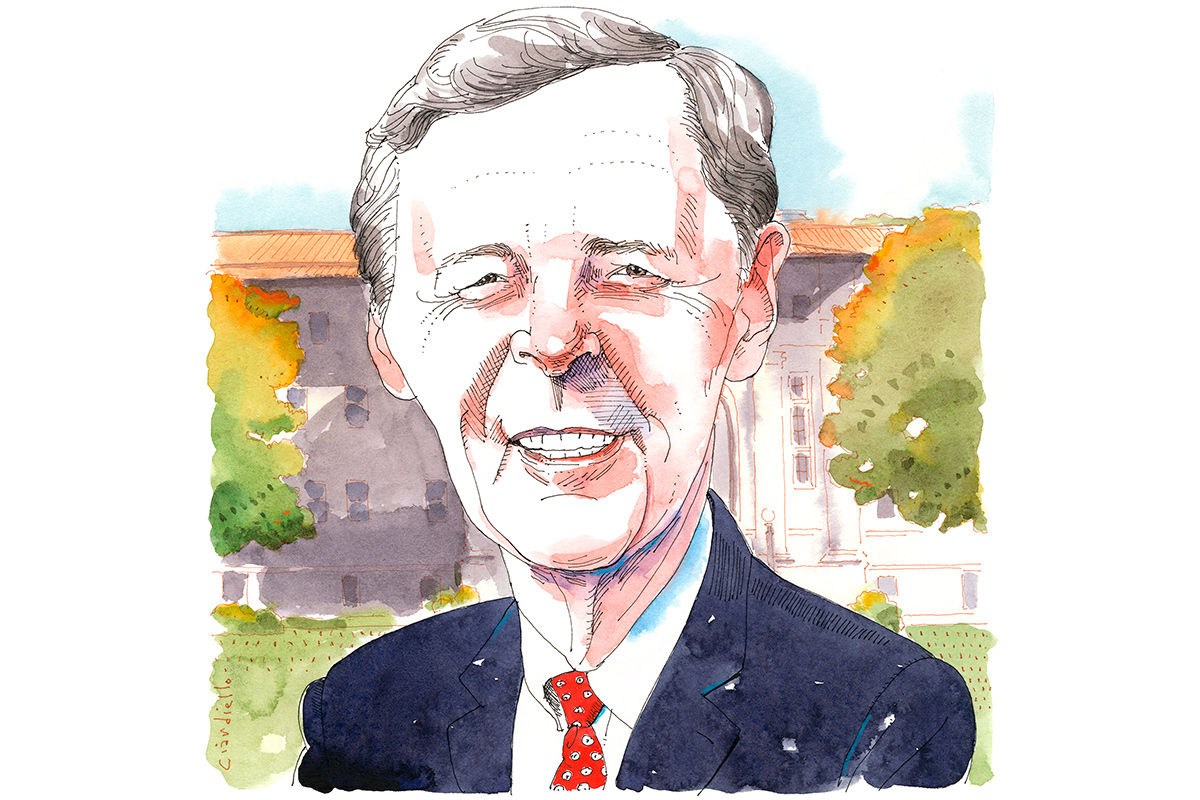

“As an institution that challenges itself, in the words of our vision statement, to be ‘ethically engaged,’ Emory has not been well served by representatives of the university in this history of misreporting,” said President James Wagner. “I am deeply disappointed.” (From the President: "Lessons Unsought," autumn 2012)

The investigation, supported by an external firm hired by the university, revealed that individuals in both the Office of Admission serving Emory College and the Office of Institutional Research annually reported admitted students’ SAT and ACT scores—as opposed to enrolled student scores—since at least the year 2000, with the effect of overstating Emory’s test scores. The report found that class rankings were also overstated, although the methodology used was not clear. Employees responsible are no longer at Emory, and a corrective action plan is being implemented to ensure future data integrity.

“Obviously, the discovery of discrepancies in admission data reporting was shocking,” said Isabel Garcia 99L, president of the Emory Alumni Board. “However, President Wagner and the administration’s decision to immediately self-report and provide the corrected data in time for the new rankings exhibited the strength of character and integrity expected of all members of the Emory family.”

The investigation originated in May, when John Latting, Emory’s new dean of admission, began to compare the statistics for his first admitted class with those of the previous year. It was quickly apparent, he says, that something didn’t add up. Within a few days, he placed a call and wrote a memo to the office of Provost Earl Lewis.

“It was stressful,” he admits. “But I was immediately reassured by the seriousness with which the university responded and the decision to conduct an investigation.”

Emory’s findings were released less than a month before the US News & World Report rankings were published September 12. Emory remains at No. 20, supporting a previous US News statement saying, “Our preliminary calculations show that the misreported data would not have changed the school’s ranking in the past two years and would likely have had a small to negligible effect in the several years prior.”

Reaction was mixed among students, but many have defended the university’s actions. “Instead of sweeping this under the rug and making silent changes, things were made public and with full disclosure,” wrote Stephen Fowler 16C in the Emory Wheel. “Emory stresses ethics and ethical decisions, and I feel even more confident enrolling here because of those decisions.”

The corrective action plan includes a new system of checks and balances and staff dedicated specifically to “providing oversight and review of all procedures and policies associated with collection and reporting of institutional data.”

The Emory investigation also brought fresh scrutiny to the rankings systems, which some higher ed experts feel are inevitably flawed and carry too much weight with the public.

“An education at Emory is the sum total of many distinguished components that are difficult to aggregate and rank in one numerical grade,” says Lewis.

That’s one reason Latting is focused on strengthening the recruitment process. “The numbers are important,” he says, “but the bigger story is more complex.”