The Importance of Being Merle

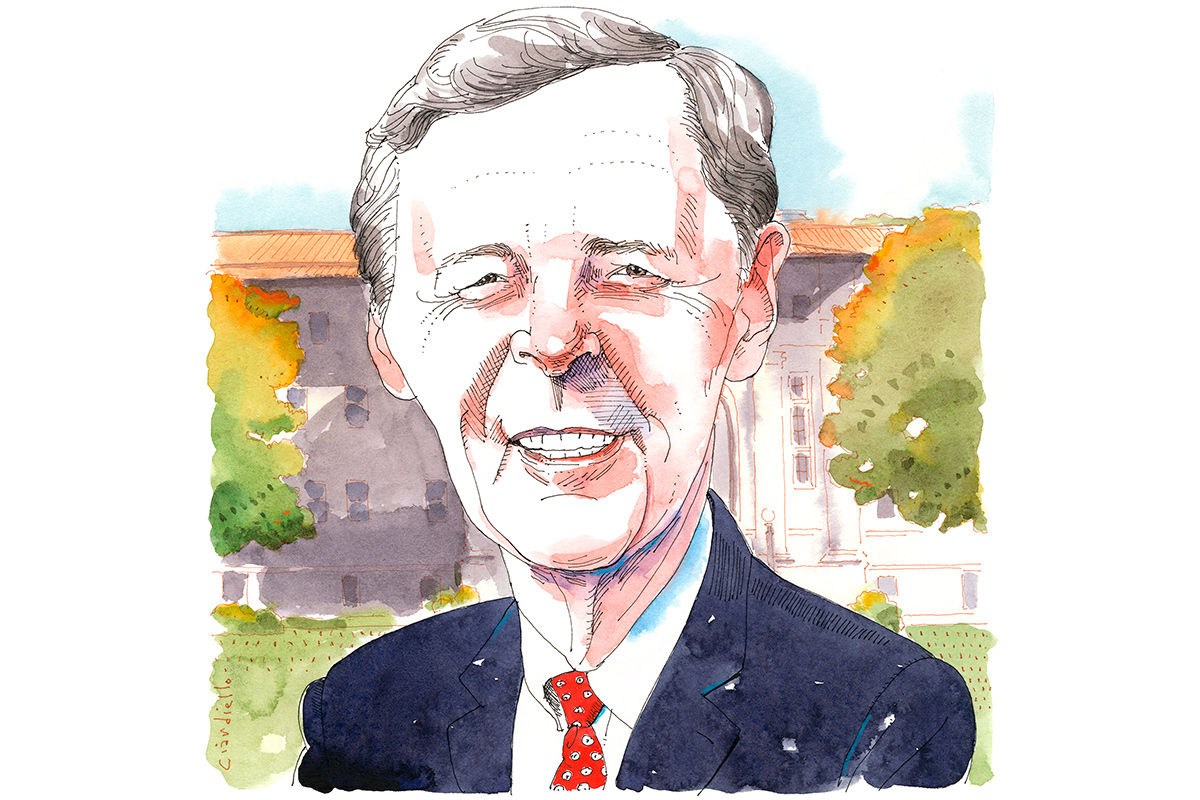

How Emory political scientist Merle Black became the voice of Southern politics

Illustration by Joe Ciardiello

A lot of political reporters keep Professor Merle Black on speed dial, but they may have to wait until after class for his call back—deadline be darned. He typically teaches two courses a semester.

Kay Hinton

In 1961, Merle Black began shuttling between two worlds that could not have seemed more different.

As a nineteen-year-old freshman history major at Harvard, he'd seen the university, a bastion of East Coast liberalism, go crazy over the election of alumnus John F. Kennedy as president.

Then, for his summer job as a roustabout at a gas distillation plant, he traveled to a small town in East Texas, a place soaked in working-class conservatism, where the civil rights movement was still years away from gaining a toehold.

Coming from a family where money was never discussed, Black was shocked to hear his fellow laborers complain—in very colorful terms—about the bite that income taxes took out of their paychecks. During the course of the three summers he worked at the plant, he also was keenly aware of his coworkers' distaste for the gradual undermining of segregation by the federal government.

"I got a real education on race and economics while I was there," Black now recalls. "I was seeing the first signs of disaffection with the Democratic Party in the deep South."

The seeds of interest in this social change that were sown in those early years grew long ago into what, for Black, became a distinguished career as the country's leading scholar on the subject of Southern politics—a distinction shared with his twin brother, Earl, who taught at Rice University until his retirement. Beginning in the late eighties, the two have coauthored four books considered essential reading in the political canon.

As Asa G. Candler Professor of Politics and Government at Emory since 1989—and for more than a decade before that, as a faculty member at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—Black also has enjoyed nearly unprecedented longevity as one of the nation's most-quoted political pundits. Even as he enters his eighth decade, Merle Black remains a go-to source for reporters looking to understand the political implications of current events, as well as to net an up-to-the-minute analysis of the election season.

Just this fall, the outlets seeking Black's insight have included: the Christian Science Monitor in a story on the political fallout of Chick-fil-A CEO Dan Cathy's comments about gay marriage, the Weekly Standard in an article about the Democrats' chances of hanging onto Southern legislative and congressional seats in the fall elections, the Associated Press (AP) for a piece about whether Ann Romney's convention speech revealed too much personal information, and the AP again for a post-convention look at how uncivil political discourse has become.

Bill Shipp, the veteran newsman known as the dean of Georgia political journalism, says he and other reporters have long placed confidence in Black's skill for summing up the political landscape. Says Shipp: "I don't think there's anyone equal to Merle in terms of talking about the political climate of the South."

Black's cramped, shotgun office on the second floor of Tarbutton Hall, which looks out on the Woodruff P. E. Center, is notable for what you expect to see, but don't. Whereas most academic chambers are piled high with books, Black's has only a relative handful, mostly stacked atop a filing cabinet near the door. Instead, the floor-to-ceiling bookcase that takes up the entire east wall of the room is filled with large binders—somewhere between two and three hundred of them, estimates Black, who's never taken the time to count them.

The binders do not, however, contain course notes or teaching guides, again as one might expect. Instead, they're stocked with exit-poll data from voting districts across the country, going back to 1976—the year a little-known governor from Georgia was elected president.

Taped to the wall next to Black's desk is a busy mosaic of charts and graphs. Here's a timeline showing the growing importance of political ideology in party identity; another tells, at a glance, how the percentage of white Christians in the Democratic Party declined as the number of minorities and non-Christian whites rose over the past four decades.

Scholars who make political science their life's work often can be divided into one of two camps: those who place the emphasis on the science, and those whose primary interest lies in the politics. By all accounts, Black is at heart a political junkie with a head for applying the tools of the social scientist.

"Sometimes political scientists can get caught up in the numbers or the methods," explains his colleague in the Department of Political Science, Associate Professor Andra Gillespie. "But Merle has a great sense of realpolitik."

Longtime political reporter Tom Baxter, who spent twenty-seven years at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, agrees that Black manages to walk the tightrope between ivory-tower scholarship and down-in-the-trenches observation.

"I don't think he'd deny being an empiricist," Baxter says. "He's very into the minutiae of polling numbers and what they mean. But he also loves to talk to political operatives and reporters to get their opinion. He likes to stay plugged in and up to date."

Longtime Emory political science professor Alan Abramowitz, whose office is next to Black's, says his colleague—whom he first met at a symposium in 1978—"combines a strong academic background and knowledge of history with a practical grasp of Southern politics gained from living through it and always talking to people. Not all political scientists have that kind of feel for the real world."

For Black, all of the data, the poll numbers, and the charts contribute toward one overarching goal: "My interest has always been explaining politics to a general audience so people can apply it to their own experience. You describe what's going on and then you say, so what? What does it mean?"

This ability to apply a broad perspective to specific current events is what sets Black apart from most other researchers, says Whit Ayres, a top Republican pollster and campaign strategist in Washington, D.C. "Among all academics, I can think of no one whose work is more directly relevant to those of us in the political consulting industry," Ayres says. "For instance, he can tell you what percentage of the white vote a candidate needs to win a certain district."

The Black twins spent a decade researching and writing Politics and Society in the South, a 1987 opus that traced the development of the eleven states of the old Confederacy from a one-party stronghold where only white voters determined the outcome of elections to a region where blacks were gaining economic and political power, the rural landscape was giving way to urbanism, and the first cracks were appearing in Democratic Party hegemony.

That book became the first in a trilogy by the brothers, followed by The Vital South: How Presidents Are Elected in 1992 and The Rise of Southern Republicans in 2002, all published by Harvard University Press.

Call it good fortune or foresight, but the Black twins' chosen specialized field of study has handily coincided with the biggest story in American politics in the twentieth century: the near-total shift of the South from staunchly Democratic—or Dixiecratic—to solidly Republican.

"Since the South is the largest region in the country, this change in American politics would have a great impact on the rest of the country," says Black, as he animatedly describes how this transformation was accelerated by GOP icon Ronald Reagan. In the first half of the century, he explains, the two parties were separated more by geography and history than ideology: the South was conservative but overwhelmingly Democratic while the liberalism of the Northeast was more politically diverse, home to both the Kennedy clan and the Republican Rockefellers.

"Reagan was the first really successful conservative politician," Black says. "Since the thirties, the Republicans had been the minority party, and it was assumed that the House would always be controlled by the Democrats. But Reagan helped unite conservatives under the Republican banner."

That political shift continues, of course, to the present day, as both parties become ever more ideologically homogeneous and compromise becomes a dirty word. The brothers Black described this phenomenon as well, in the well-received Divided America: The Ferocious Power Struggle in American Politics (Simon and Schuster, 2007), which further charted the ideological realignment of the parties in various regions across the country.

Black says he considers the increasingly divisive nature of current politics more interesting than depressing—adding, with a shrug: "It is what it is." But his scholar's objectivity fades when he notes that neither party is willing to make tough decisions to put the federal government back on track.

"We're in one of the worst situations as a country right now because of all of the debt and entitlement spending," he says. "We've made huge promises for programs—we're talking about trillions of dollars—but we don't know where the money's coming from."

Born in Oklahoma, Merle and his twin brother—his elder by fifteen minutes—were brought as toddlers by their parents to Sulphur Springs, Texas, about eighty miles northeast of Dallas. At the time, their father helped farmers recover from the dust bowl as an employee of the Soil Conservation Service, one of the first programs created by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Later, Black would see how people butted heads with the federal government when his dad changed jobs to a position in which he was responsible for enforcing watershed regulations.

He got an early glimpse of politics at work as he watched his mother hand-counting ballots as a vote tallier at the local precinct. He recalls his father, a staunch Democrat, watching the 1952 political conventions and discussing the Eisenhower-Stephenson race of that year. By the time Black left for Harvard, he'd developed a strong interest in history and the dynamics of social change. But it wasn't until he'd seen the early signs of alienation with the Democratic Party during his first summer at the distillation plant that he switched the focus of his studies to government and political history.

After graduating magna cum laude from Harvard in 1964, Black joined the Peace Corps, teaching elementary school in the West African nation of Liberia for two years before enrolling in the University of Chicago. For his doctoral studies, he changed direction again, moving from an initial focus on global politics to the wide-open field of Southern politics.

In 1970, Black accepted an instructor position in political science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), where he taught the college's first course dedicated to the study of Southern politics. It was in the early eighties that reporters from the New York Times, Associated Press, and other publications began regularly calling Black for his insight into voting trends and predictions about particular races. Moving to Emory in 1989 helped boost his profile by virtue of being closer to CNN and thus more accessible to national television.

Larry Sabato, director of the oft-cited Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, says Black's popularity as a pundit stems in part from his talent for making the complex easily understandable.

"As a classroom teacher, he knows how to explain complicated subject matter and is good at communicating a lot of information in a succinct way," Sabato says.

Also, adds journalist Shipp, Black's analyses are untainted by personal politics.

"If you wanted an unbiased overview of a particular district or race, you'd call Merle," Shipp says. "You could take what he tells you, hold it up to the light and not be able to see any color."

Pollster Ayres was a grad student at UNC in the mid-seventies when Black was head of graduate studies there. "He was a superb scholar and teacher," remembers Ayres, who later briefly joined Earl Black on the faculty at the University of South Carolina.

Asked how to tell the twins apart, he's momentarily stumped. "They look alike, they sound alike, and they're partners in the same field of research," he says, laughing.

When Ayres launched his polling career in Atlanta, he again caught up with his former instructor, who'd come to Emory in 1989. Together with the AJC's Baxter and other political operatives, they formed what was called the Political Junkies Book Club. The group met monthly, ostensibly to discuss the latest book on politics, but mostly to swap observations and opinions about current races, candidates, and political trends.

Ayres believes that much of the Black brothers' renown stems from the fact that, instead of churning out articles for scholarly periodicals that are read only by other academics, they apply their "clear and methodical analysis to writing books that are widely read and quoted and have a much longer shelf life."

Those books have ensured the twin professors an unrivaled authority in their field. Charles Bullock, the University of Georgia's foremost political science expert, says, "It'd be hard to imagine anyone doing research into Southern politics and not citing one or more of their books. I've used them in my own classes."

Over the decades, the Blacks have spent a good deal of time on TV and radio talking about their books. But that doesn't mean Black seeks out the limelight, says his colleague Gillespie. "He's quite generous" in his willingness to refer a reporter to another professor who's better versed on a particular subject.

Black has had occasion to meet plenty of his research subjects over the years, but a few stand out. Just before coming to Emory, he says, he attended a campus appearance at UNC by then-Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton, who at the time was still trying to live down his lackluster keynote address at the 1988 Democratic Convention in Atlanta.

As Clinton lingered on the quad to discuss and debate issues with conservative students, Black recalls, "I thought to myself, 'This guy's pretty sharp. This is someone the Democrats could really use.' "

Now, more than twenty years later, Black still calls Clinton "the best natural political talent I think I've ever seen."

Black himself is a noted workaholic who, when not teaching his two courses a semester or giving interviews, is happily reading up on various campaigns. Married since 1981, Black and his wife, Debra, have two grown daughters, one of whom—Julia Black 08C—graduated from Emory. At seventy, with four decades of teaching behind him, Black appears to have no thoughts of retirement.

"Despite his seniority, Merle hasn't slowed down at all," says Dan Reiter, who chairs the political science department. "He's highly dedicated to his students and his research."

Even though he's taught most of his courses many times over the years, Black still gets excited when his students are engaged by the material.

"The class I enjoyed most last year was a freshman seminar where the students simply came in and talked about the books we were reading," he says.

As for the presidential election, Black hasn't made a solid prediction. But if you follow political coverage in print or on TV, you're pretty much guaranteed to see Black quoted—and it would be a good idea to pay attention.

Sound Bites

Emory faculty experts help drive political news and views

"What you are seeing reflects some of the ideological division within the Republican party between the center right and the far right."

—Barkley Professor of Political Science Alan Abramowitz in Bloomberg News, on the impact of candidate Todd Akin's comments about rape

"The good thing about this current era is that whites are more receptive and open to voting for African Americans. There are some whites out there who won't vote for black candidates, but this is certainly not true of most white voters. It's not so much about race anymore as it is about party."

—Associate Professor of Political Science Andra Gillespie, on the international news site France24.com about the "Obama effect"

"Even though there might be some degree of apathy and distrust of the electoral process, I think a lot of people are going to turn out on election day. We should have hope that citizens recognize that . . . elections really can matter in the lives of families and individuals, particularly in African American communities."

—Associate Professor of Political Science Michael Leo Owens on WABE's "All Things Considered," about voter turnout

"In studying voters' responses to a range of messages, we discovered that Americans understand that our government is bought—and they want it back. You just have to speak with them in ways they can hear."

—Psychology Professor Drew Westen in a New York Times opinion, "How to Get Our Citizens Actually United," about the Fair Elections Bill

Gay rights "was never the most salient thing for African-Americans. . . . Race is still important, poverty is still important, and the Democrats are still the party that does a better job of advocating on those issues, in their view."

—Andra Gillespie on NPR, on whether Obama's support of gay marriage will turn off black voters

"There's a very strong division among white voters that didn't used to exist, or used to be very small, based on religious beliefs and practices. For the people who care about them, on those issues, it's very hard to compromise."

—Alan Abramowitz on NPR, about growing divisions among voters

"These days . . . you've got a generation of working class folks in the Deep South who have no memory of the Southern Democratic parties that produced Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton."

—Associate Professor of History Joseph Crespino in a New York Times opinion, "Moderate White Democrats Silenced"