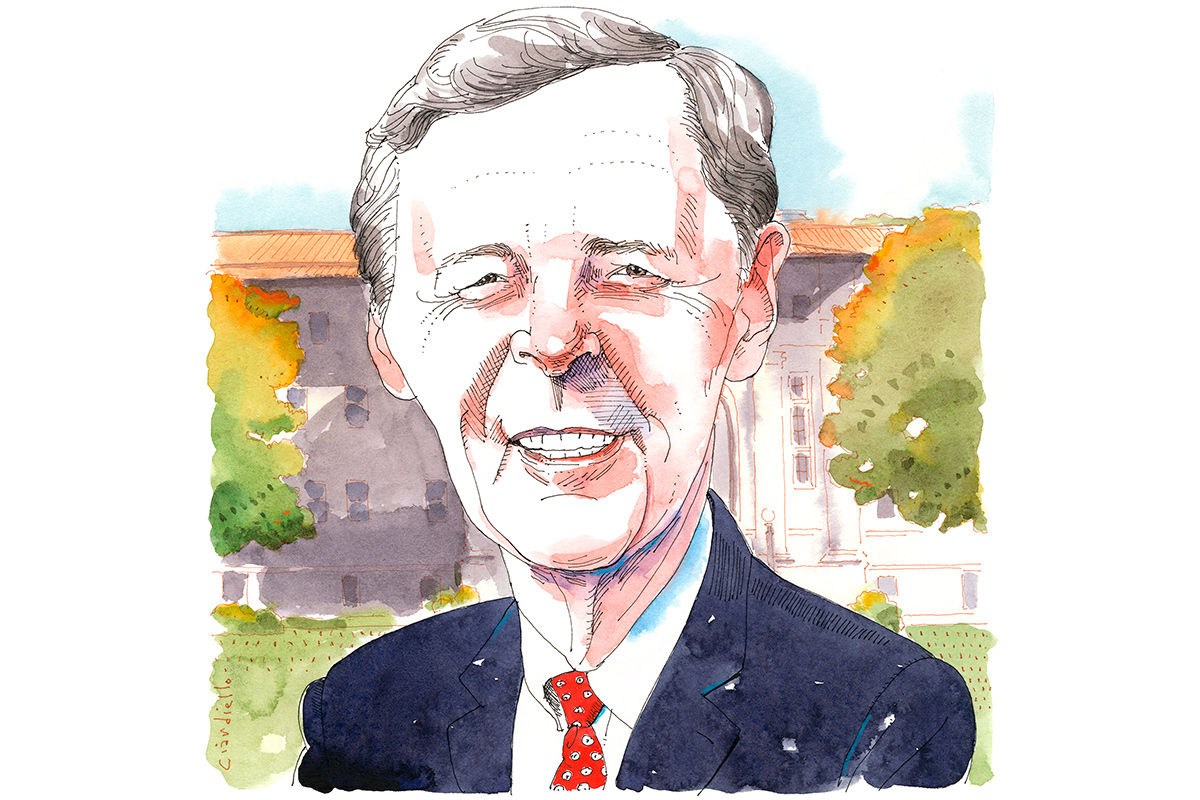

'What We Care About'

New dean of admission is reshaping recruitment

Kay Hinton

“Here’s where you talk about Wonderful Wednesday. And while you’re at the WoodPEC, you only talk about Swoop, not Dooley yet. When you get to the Dooley statue, that’s when you tell them about Dooley.”

It’s Friday morning in Emory’s Office of Admission, and Jessica Vaccaro is training a student tour guide, walking him through the route and various stops via her computer screen. Other tour tips: it’s okay to joke about how messy a “typical” dorm room might be; wear a watch, don’t pull out your phone to check the time; and if a prospective student is passionate about college football, let’s face it, Emory may not be the best fit.

The admission office, completed in 2010, is spacious and stylish, looking out onto a landscaped courtyard; the two floors below house the Emory Barnes and Noble and a never-empty Starbucks. Along the lobby wall is a series of poster-size hallmarks of university history, including one titled “Human Wisdom and Moral Integrity.”

The notion of moral integrity is a delicate subject at this particular place and time, where the aftershock of an unwelcome revelation last spring can still be felt. In May, John Latting, assistant vice provost for undergraduate enrollment and dean of admission for Emory College, discovered discrepancies in the admission data that the university provides to external organizations.

Five months later, though, Latting is once again fully consumed by the business he knows best: finding, selecting, and finally welcoming some of the nation’s most desirable college freshmen.

Even after more than two decades in admission work, Latting says, “What’s so exciting is, there’s still that sense of . . . there are three million kids graduating from high school, and they want to go to college somewhere. That’s our talent pool. Now how can we tell our story in a way that helps us grow the number of outstanding students who consider us?”

Before coming to Emory, Latting, who has a PhD in education policy and management research from the University of California, Berkeley, spent ten years as dean of admission at Johns Hopkins University. In January, he arrived at Emory at a historic time, taking the helm of an office that had seen considerable staff turnover and was struggling to define a communications vision.

Latting’s wife, economic historian Caroline Fohlin, also joins Emory as a distinguished visiting professor in economics; her second book, on financing industrial growth, appeared late last year. The couple has three children.

Since his arrival, Latting has been working to cultivate a strong team, including, most notably, several positions that are wholly focused on aspects of communication and outreach to potential students. On a deeper level, though, he’s attempting to create a culture shift—one that empowers the university’s admission program to be more proactive in targeting students who are right for Emory and vice versa. It’s easy for competitive schools to let recruitment be driven by external forces and assumptions about public opinion, he says, but a better approach is from the inside out.

“The public will define for you, as an admissions officer, what the criteria and the process are,” Latting says. “You can give in to that, or you can take control of your process. You can say, SAT scores are important, but these are the things we really value. We have begun an exercise of digging down to the roots of what qualities we are looking for and how we measure them—not just taking things at face value and letting the public tell us what we care about.”

Of the three fundamental qualities Latting looks for in an Emory student, the first is a genuine desire to learn. That may sound simple, but it’s not so easy to measure, he allows.

“It’s not just a number, it’s a pattern,” he explains. “It’s a range of evidence that all points to one conclusion. The SAT is something you gear up and do on a given Saturday, but how does a kid behave every Monday through Friday? How do teachers describe their behavior in the classroom? We’re looking for the kid who is there for the business of learning—who does the work, answers the questions, comes in after class.”

Second, Latting says, one can’t ignore the advantages of raw talent—“Of course we want bright students.” And finally, he’s looking for some evidence that applicants “have a sense of community and care about other people. There is something distinctive about Emory’s emphasis on that.”

One of the obvious challenges facing Emory and similar institutions is how to help students get financial access to higher education in the midst of a flagging economy, Latting says. But there are compelling opportunities, too—such as the admission program’s expanding geographic reach, and its ability to engage thousands of prospective students at once through new communication channels. Latting wants to focus the spotlight on Emory’s current students and faculty and forge real connections between them and future prospects.

He and the admission team also are interested in taking a fresh approach to interviews, using them as a chance for recruitment officers to draw out what’s special about a student and flex their instincts rather than just ticking questions off a list.

“I am really eager to make recruiting each new cohort of freshmen a university-wide concern, engaging alumni as well as faculty and students,” Latting says. “I’d like to be a leader in that.”