Medicine Woman

Cassandra Quave turns to traditional remedies for new weapons against modern suberbugs

Ann Borden

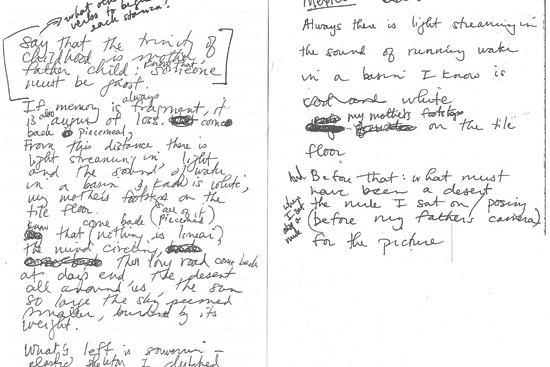

inspirations: Quave explored the flora and fauna with locals in rural Southern Italy.

Courtesy Cassandra Quave

Cassandra Quave 00C first encountered the battle against infectious diseases when she was three years old and hospitalized with a life-threatening case of staph.

"That's probably why I feel a strong connection to people who deal with these kinds of infections," says Quave, now a visiting assistant professor at Emory's Center for the Study of Human Health.

She recently received a $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to pursue her research on how an extract from a tree common in forests across Europe might help fight antibiotic-resistant staph. The five-year project, led by Quave, will include collaborators from the Emory Institute for Drug Development, the University of Iowa, and Montana State University.

Prolific use of modern drugs has helped turn multi-drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) into the leading cause of invasive disease, killing more people every year than AIDS. Quave believes the remedies of traditional healers may lead to better ways of treating it. "Ideally, we should combine the best of both modern medicine and complementary alternative medicine," says Quave (rhymes with "wave"). She bridges the two worlds as a medical ethnobotanist, studying human interactions with plants.

At thirty-four, Quave already has a utility patent for one promising medicinal plant extract and has filed a disclosure for a second patent. In 2011, she formed the bio-venture startup PhytoTEK with Emory friend Sahil Patel 00B, who is now at Harvard Business School. PhytoTEK advanced to the final round of Harvard Business School's Alumni New Venture Contest, placing in the top three.

Quave grew up in the small town of Arcadia, in a rural area of South Florida, where her mother was a teacher and her father ran a land-clearing business. She had multiple congenital birth defects of her skeletal system, including missing part of her right calf bone. When she was three, her right leg was amputated below the knee in an effort to improve her mobility.

"The doctors told my mother not to unwrap the bandages, but she noticed this horrible stench coming from my leg and knew that something wasn't right," Quave says. "As she took off the bandages, the flesh just fell off the bone." The toddler returned to the hospital for treatment of a severe staph infection. Her leg had to be cut off even shorter, leaving her with a heavily scarred stump that lacks fatty tissue, making prosthetics less comfortable.

Like many kids, though, Quave enjoyed playing in the dirt or climbing a tree to be alone with a good book. "I'm so glad my parents had the strength not to help me do everything," she says. "That made me independent. It takes a special person to raise a disabled child."

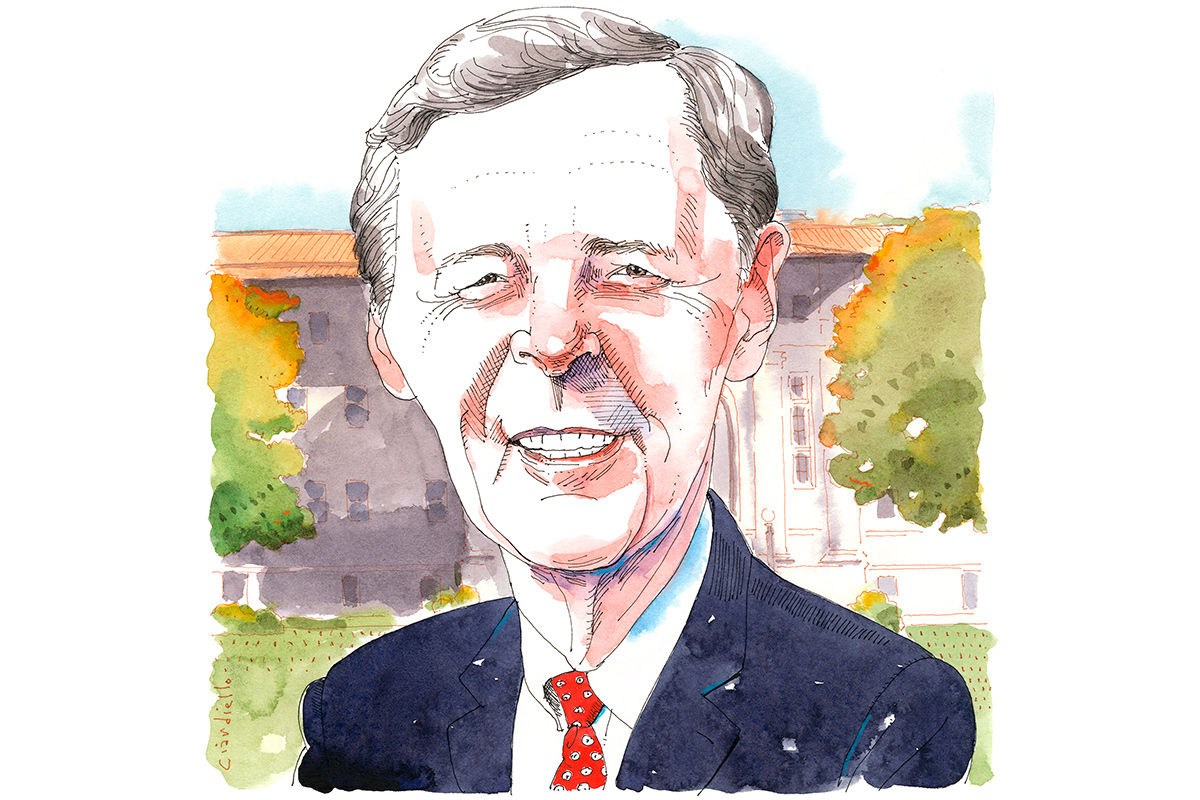

As a child, Quave endured several operations and infections that sparked her determination to help others.

Courtesy Cassandra Quave

During high school, she learned to operate the bulldozer and backhoe parked in the family's yard, so she could help her father on summer breaks. She excelled in science fairs, competing at the state and international level. For her first science project, in the sixth grade, she took saliva samples from her dog, a horse, and a cow for a comparative analysis.

Nearly every year, Quave had to return to the hospital for more operations on her leg. She later made history as one of the first amputees to have bone lengthening surgery. "They broke my femur and implanted a kind of knob that you twist," Quave explains matter-of-factly. At thirteen, she developed scoliosis. Metal rods were surgically implanted in her back. She also had hip dysplasia, requiring her pelvis to be broken and rebuilt.

One bright spot in her storm of medical problems was pediatric orthopedist Chad Price 67C. He performed almost every surgery on Quave, except for the initial leg amputation, and became a friend and mentor that Quave still consults. "I was a very odd, inquisitive kid, and Dr. Price took the time to listen to me and answer all of my questions," Quave says. "He is different from most surgeons; he's almost like a traditional healer in the way that he connects with patients. I remember once when I was coming out of anesthesia, and I was crying because it hurt so much, Dr. Price lay down in the bed next to me and held me."

In eighth grade, Quave started volunteering at the local hospital. "I would spend Friday and Saturday nights watching doctors perform procedures in this small-town E.R. I'd make sure the patients were comfortable, bring them blankets and things," she says. "I definitely had a gift for communicating with people who were sick." When her mother insisted that she get home before two a.m., Quave recalls arguing, "That's when all the good drug cases and bar fights start coming in."

Following in the footsteps of Price, Quave earned her undergraduate degree at Emory, majoring in biology and anthropology. She planned to go on to medical school and become an orthopedic surgeon. But a different path opened up when she took a tropical ecology class from Larry Wilson, adjunct faculty in Emory's department of environmental studies and an ecologist at Atlanta's Fernbank Science Center. Under Wilson's tutelage, Quave spent several months in the Peruvian Amazon, researching the therapies of traditional healers.

An acceptance letter to medical school was waiting for her when she returned to Atlanta during her senior year at Emory, but the Amazon had changed Quave. She no longer wanted to be an MD. A chance meeting with an Italian ethnobiologist at a conference led Quave to southern Italy, where she conducted field research on the traditional remedies of rural people there and eventually wrote a sort of cookbook of traditional medicine in the region. Quave also fell in love while in Italy, marrying Marco Caputo, a resident of the tiny town of Ginestra; they now have two young children.

Back in the United States, Quave pursued a PhD in biology at Florida International University, where she focused on an ethnobotanical approach to drug discovery. "I felt strongly that people who dismissed traditional healing plants as medicine because the plants don't kill a pathogen were not asking the right questions," she says. "What if these plants play some other role in fighting a disease?"

She led a project to analyze extracts from one hundred different species of plants she had collected in Italy, guided by clues from hundreds of interviews with locals. She was particularly interested in finding treatments for skin and soft-tissue infections to help in the fight against MRSA. This "superbug" bacterium can cause everything from mild skin irritation to death, and is difficult to treat because it's constantly adapting and has become resistant to many antibiotics. It is common in people with weak immune systems in hospitals and nursing homes.

People with implanted medical devices, like knee or hip replacements, also are at higher risk since the implants provide a smooth surface that the sugary matrix of the bacteria can adhere to. Even more alarming, MRSA infections are on the rise in healthy young people outside of hospitals.

Quave is uncovering promising ways to treat MRSA by teasing apart leaves, stems, roots, and bark, isolating individual plant compounds for analysis. Her first patent involves a compound from the roots of an Italian elm leaf blackberry that neutralizes the staph defense system. "Think of it like Star Trek," she says, explaining that after MRSA attaches to something, it can grow a biofilm that acts as a shield against antibiotics—much like a villainous space ship uses a force field to ward off attacks from the Starship Enterprise. The plant extract prevents the MRSA bacteria from attaching to anything, so it can't throw up a force field.

Quave hopes the extract could one day be used to coat artificial implants and catheters before they are implanted, preventing MRSA from ever gaining a foothold on them. The recent NIH grant she received will further her research on a second compound from a European tree, "Extract 134," which inhibits the toxic effects of MRSA. "One reason that MRSA can infect healthy people is that it's really good at producing a ton of toxins that it shoots out like lasers to cause tissue damage," she says. "Extract 134 turns off the MRSA system responsible for toxin production. The bacteria are still able to grow, but the weapons are turned off."

Taking away MRSA's tissue-damaging weapons or its force field could tip the battle back in favor of the host's immune system, with little or no help from antibiotics, Quave theorizes. "It's more of a delicate approach. The goal is to improve patient therapy, reduce infection rates, and avoid creating more virulent strains of MRSA," she says.

After a postdoctoral stint at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Quave returned to Emory last fall. She was recruited by another one of her longtime mentors, Michelle Lampl, a physician and anthropologist who heads Emory's Center for the Study of Human Health. Lampl founded the center last year to serve as a nexus for Emory's diverse efforts in health education, research, and practices.

Quave teaches a course on medical botany while pursuing her drug discovery research that will draw on expertise from anthropology, biology, chemistry, and environmental studies. High hurdles remain to getting the plant-based MRSA treatments from the laboratory into clinical trials, but Quave is undaunted. "I'm used to obstacles," she says. "I've climbed a lot of brick walls in my life."