SURE Thing

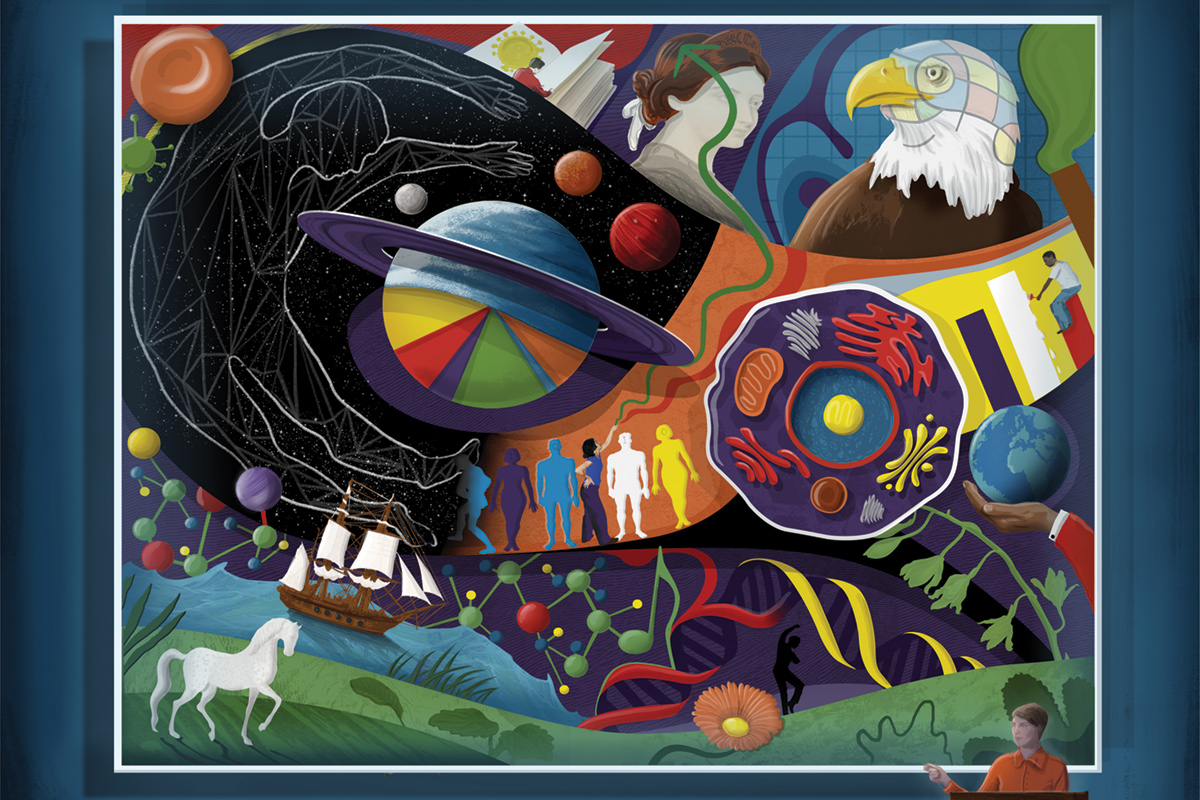

Undergraduate research gets real—and gets results

Kay Hinton

This past summer, ninety-six Emory College of Arts and Sciences undergraduates took a deep dive into the world of research through a renewed initiative known as SURE.

The Summer Undergraduate Research at Emory program, or SURE, provides those students with ten weeks of fulltime, mentored, independent research working directly with professors in disciplines from philosophy to psychiatry. Two dozen of the student researchers attend partner institutions such as Agnes Scott and Morehouse Colleges, while six are Oxford College students.

The rest, like rising senior Kaela Kuitchoua 18C, are Emory College students who traded in a summer of flip-flops and beach reads for lab coats and access-card lanyards.

“Classes help explain previous research, but having the summer to devote to research is the real-life experience that makes what I’ve learned come alive,” says Kuitchoua, a neuroscience and behavioral biology major.

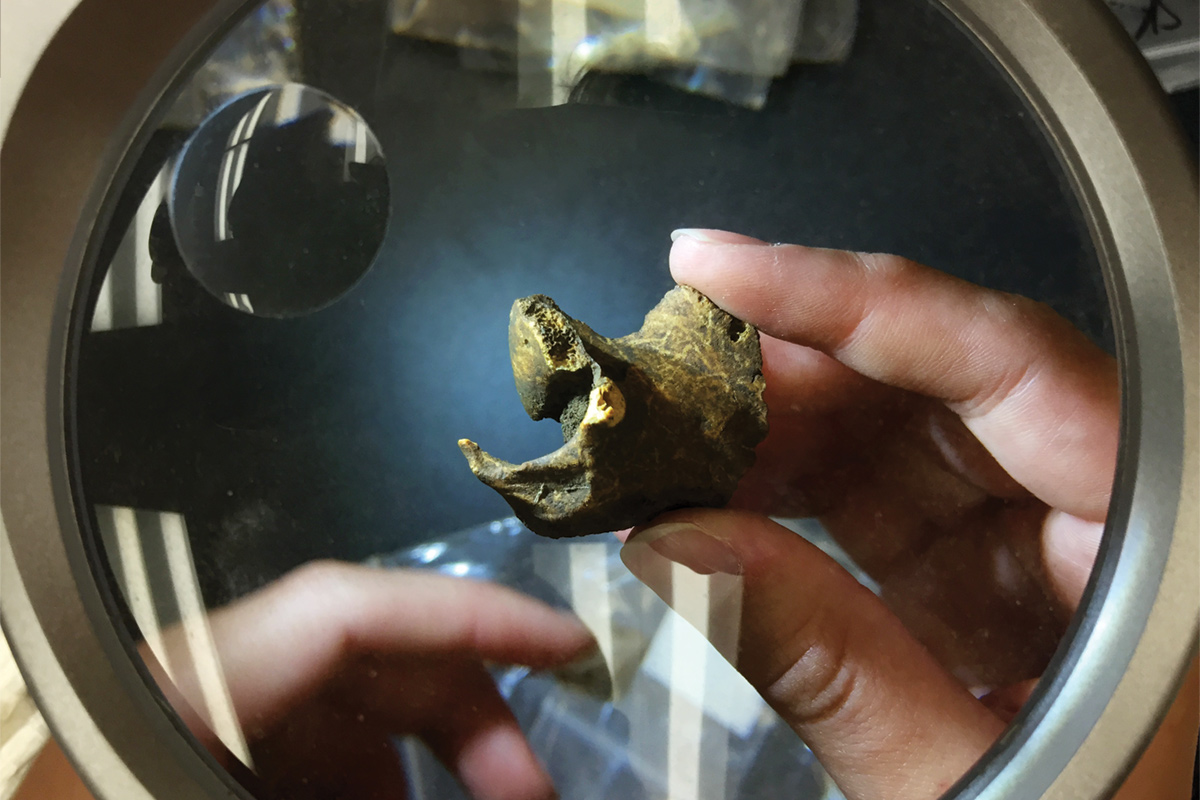

She has spent the summer working under an associate professor at the School of Medicine. Her job is to analyze MRI scans of socially housed Rhesus macaques that were raised naturally by good, competent mothers, or who received poor care from their mothers.

“It’s really allowed me to become more independent,” Kuitchoua says.

SURE is a continuation of an Emory initiative started twenty-eight years ago to support students in the natural sciences. Last year, Emory College’s Undergraduate Research Programs merged a parallel program in the social sciences and humanities with SURE to encompass all fields, says Gillian Hue, SURE director.

Students accepted into the highly competitive program live together on campus, comparing notes across disciplines and schools. Weekly workshops help explain best practices such as how to navigate research literature and what to expect in graduate school.

Informal and programmed lunches and dinners also let the students discuss current issues in research, such as ethical concerns or digital work. But students spend the bulk of each week, at least forty hours, conducting research. Work in the hard sciences tends tobe tied more to the mentor’s research, while humanities and social sciences work tends to be more independent.

Cynthia Willett, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Philosophy, is helping direct a project for Mike Demers 18C as she attends to her own work in Europe. Demers, a philosophy and comparative literature major, is conducting an extensive study of the classical philosophical question of knowledge, with attention to how it implicates efforts to understand the current political climate.

Using his readings of French philosopher Henri Bergson as a baseline, Demers aims to show how particular facts may only encompass part of a truth or reveal a bias of the user.

Take the debate over crowd size at Trump’s inauguration. Demers says the political debate moved from facts into the grayer area of what that number meant.

“There was a conclusion some made that even if the crowd in the photo of Trump’s inauguration is smaller, he still has a broader cultural mandate legitimizing, in an almost universal manner, every decision he makes while governing. And that is much harder to classify as simply a disinterested, logical appeal to fact,” Demers says. “That changes how we understand how facts are used and suggests that often they fail to achieve freedom from the influence of bias and incomplete understanding.”

The highly competitive SURE program not only brings students from other institutions to Emory, it sends undergraduates to research labs and on projects across Emory’s nine schools.

“We get great students who learn so much more than research,” says Folashade Alao, the director of Undergraduate Research Programs in Emory College. “SURE is designed to open all of the avenues available to them when they have developed the planning, writing, and analyzing skills that the best research requires.”

Kuitchoua is working at Yerkes National Primate Research Center under the guidance of Mar Sanchez, a Yerkes researcher and an associate professor in the School of Medicine.

Sanchez’s lab works to understand the effects of social experiences on primate brains, specifically how early social experiences and maternal care affect the developing brain.

That calls for observation of the monkeys that live in social groups at the Yerkes field station, watching for the good and suboptimal care that monkey moms naturally provide their offspring. The work will translate into better understanding of maternal care in humans and could eventually help provide interventions for, say, helping foster children cope with early trauma.

“This is very difficult work for an undergraduate to do, with a very long learning curve,” Sanchez says. “It requires a significant amount of ethical thought and intense training, but it’s very rewarding for mature and motivated students.”