Think Again

Emory looks to lead in education innovation

David Kulp 20C felt somewhat anxious when he signed up for an introductory chemistry course at Emory last year.

Understandably so. His last taste of chemistry dated back to sophomore year of high school. On top of that, he spent a gap year away from the classroom.

Now he was putting his dream of a medical career on the line with a deep plunge into basic chemistry that, while not a true weed-out class, could still prove extremely abstract.

“I’m more of a big-picture guy,” he says.

Fortunately for him and his classmates, timing was good. They were the first students in Emory’s College of Arts and Sciences and Oxford College to experience a pilot program of the Department of Chemistry’s major overhaul of everything from introductory courses to capstone senior seminars. Called “Chemistry Unbound,” the program is one of the first from a major research university to completely rethink the way chemistry is taught.

“The idea is that you’re not just learning the facts, but also learning the chemistry behind how the world works,” says Doug Mulford, a senior chemistry lecturer and director of undergraduate studies for Emory’s chemistry department. “You’re also seeing how to construct a scientific claim and use evidence and reason to explain your argument. That level of critical thinking transcends chemistry.”

Four intradisciplinary courses take the place of yearlong studies of sub-areas such as organic and inorganic chemistry. The new program provides a more cohesive grounding for the many students who take foundational chemistry into other fields.

“It’s still science, just more understandable,” says Kulp, now comfortably in his sophomore year with medical school still in his sights.

Chemistry Unbound: Emory is among the first major research universities to completely overhaul its chemistry curriculum in response to real-world needs.

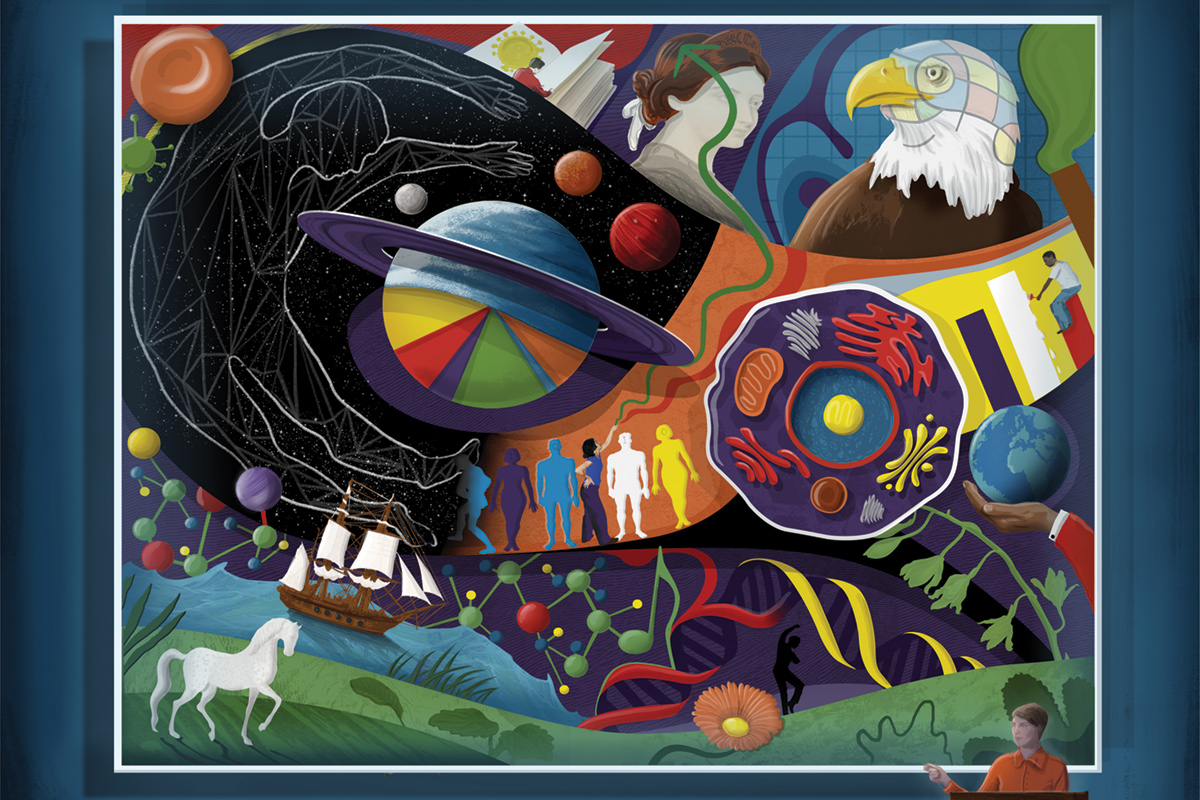

Emory’s drive for academic excellence begins in the classroom, where the research enterprise meets innovative teaching and a comprehensive curriculum that emphasizes how to weigh evidence, encourages difficult questions, and brings students and professors together in the process of discovery. The college is prioritizing support for teaching excellence, creativity, and innovation that builds on existing strengths to make Emory a national leader in delivering a liberal arts and sciences education.

Take the class The Ferguson Movement: Power, Politics, and Protest. Mackenzie Aime 18C, who is interested in public health and food science—a blend of biology, chemical engineering, and biochemistry—says the class “was one of the most transformative, personally and intellectually” she’s taken.

The course was convened by three instructors from different disciplines—Dorothy Brown, professor of law; Pamela Scully, professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, and professor of African studies; and Donna Troka, an adjunct assistant professor in the Institute for the Liberal Arts. Together with a roster of nearly two dozen faculty from public health, business, law, medicine, and theology, they addressed the August 2014 police shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, within the larger discussion of race, politics, and power in the US.

The class taught Aime, an Idaho native, the importance of bringing race and social issues into other classes. “I started thinking about what social problems are not being talked about in hard science classes,” she says. “These things are often left out of the conversation.”

Likewise, students who sign up for the Shipwrecks, Pirates, and Palaces course taught by Sandra Blakely, associate professor of classics, discover connections they couldn’t have imagined among accounting, globalization, responses to risk, mobility, the relationship between warfare and profit, and information flows in the ancient Mediterranean.

Blakely recalls hearing a few years ago from one of her students after a job interview in which he described the coursework to the recruiters.

“They saw from his description that he could think across cultural boundaries when it came to issues of the creation of value, the way economies are embedded in larger cultural structures, and our own limitations of understanding when we are seeking to piece together how another group thinks,” Blakely said in an email. “Those skills were immediately relevant to the job for which he was interviewing (and yes, he got the job).”

Emory’s liberal arts framework allows students to experience different perspectives and methodologies, ultimately developing more nimble thinkers.

Mixing It Up: Associate Professor Astrid M. Eckert (right) leads a history course that exposes students to a different faculty member and research topic each week

Astrid M. Eckert, associate professor of history, likens the class Perspectives on the Past to speed dating—in the sense that students meet a different instructor for each session, presenting a history topic from their research.

One week could be ancient Rome (Judith Evans Grubbs, Betty Gage Holland Professor of Roman History); another the Jim Crow era in the South (Hank Klibanoff, professor of practice in English and creative writing); and another on symbols in public life (Emory College Dean Michael A. Elliott).

Eckert, the self-described “custodian” of this departmental effort, says that, “We’re all drumming in the message that historians work with primary material. This is an evidence-based approach—it’s not coming out of thin air. Students know how to google before they get here, but we try to show them there are things you can do with a world-class research library.”

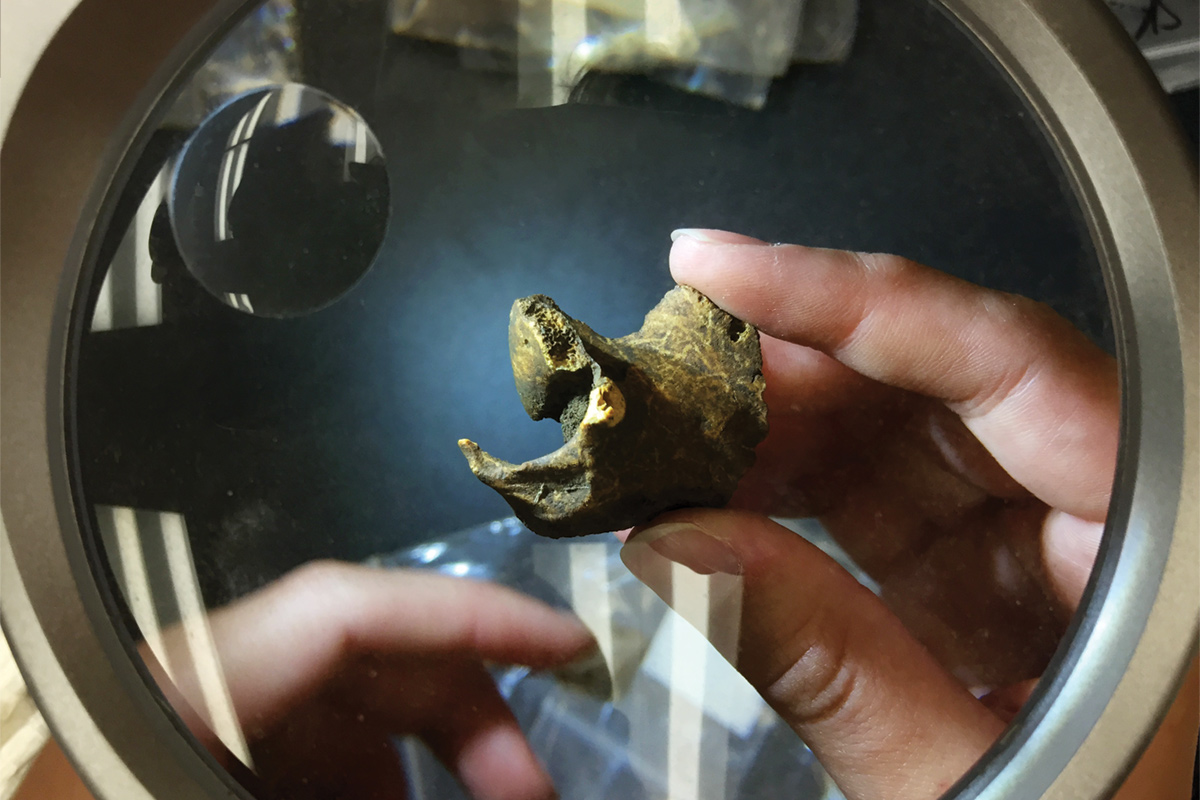

This emphasis on evidence in the curricula became de rigueur when the Emory community selected the theme of “The Nature of Evidence” for its Quality Enhancement Plan in 2014. From day one, first-year seminars give students a solid foundation in making informed decisions based on evidence as well as using campus resources such as the university’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library and the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

Anheuser-Busch recently hired one of Eckert’s students who combined a history major with a Goizueta business degree. The ability to write well, move forward on the basis of new evidence, and know how to tell stories was a good fit with the marketing department of a company that holds a 45.8 percent share of the beer market.

In the course What Does It Mean to be Human?, Kim Loudermilk, senior lecturer in the Institute for the Liberal Arts and director of the program in American Studies, shares the teaching duties with graduate students from the fields of psychology, immunology, and comparative literature. Students may not arrive at a definitive answer posed by the class, but in this case the interdisciplinary journey is the destination.

Loudermilk works with some of Emory’s most passionate young proponents of the liberal arts in the interdisciplinary studies (IDS) major. Along with the American studies major, the IDS major (ranked the No. 1 accredited integrative studies program in the US in 2017 by BestColleges.com) is the only major at Emory that allows students to structure their own program of study around a field of interest that they define for themselves. Faculty coadvisers provide up-close encouragement along the way and, in the process, have fostered a collaborative environment where IDS majors share ideas in research involving sustainability, water issues, and social implications of health care, just to name a few.

In spring 2015, the IDS department started the IDEAS (Interdisciplinary Exploration and Scholarship) Fellows program as a way to spread this interdisciplinarity more broadly across the university and address a concern that students needed to better understand the connections between their liberal arts and sciences courses.

A key moment for Loudermilk was hearing someone say that he didn’t really understand the value of liberal arts until after graduation. “It wasn’t until he had a job that he realized the issues and problems he was dealing with required more than what he learned in his major,” she says. “It required a lot of the stuff he had learned in his liberal arts classes.”

Eboni Jalea Freeman 18B joined the IDEAS Fellowship program after discovering a passion for the “combinatorial play” of other disciplines. She thoroughly enjoyed an economic-and-literature-based analysis of subliminal messaging in cosmetic marketing targeting women of color. Now, in addition to having a Google internship under her belt, she’s an enthusiastic ambassador of the liberal arts and sciences as an IDEAS Fellow.

Undergraduates from across disciplines and schools can apply—there were fifty applications for eight slots in spring 2017. They can enter the program as sophomores and remain throughout their college careers, with the veterans playing an important role mentoring the newbies. During their tenure, these twenty-four or so fellows meet weekly over lunch with IDS faculty advisers, hold special events like Professors at Kaldi’s Getting Coffee (in which professors and fellows talk over java) and plan activities for the broader student body.

For instance, IDEAS Fellows help out at Emory Telling Our Stories events. Sponsored by the Community Engaged Learning Program of the Center for Faculty Development and Excellence and usually organized around a prominent speaker (President Claire E. Sterk was featured in spring 2017), a mix of faculty, undergraduate and graduate students, alumni, staff, and administrators enjoy a meal together before gathering in smaller groups. Then fellows break out a story circle at each table.

At a fall 2017 event, Freeman led off with this question for her tablemates: Which two classes from different disciplines did they find an interesting connection between? She reports that they “discussed the beautiful balance of music, dance, and biology; the contention inherent between short-term economics and long-term environmental impact; and how tools of business ethics can be applied to global humanitarianism.”

“That Tuesday night provided a great example of how every Emory community member can learn from one another when they open their minds to new ideas and perspectives,” she says.

Coffee Talk: One of the goals of the IDEAS Fellows program is to increase meaningful interaction among faculty and students across disciplines—such as regular, casual gatherings at Kaldi's, where ideas are shared over cups of joe.

New Majors Address Changing Times

Roundtable talk. Courses that pull in faculty and students from across schools. Business students comajoring in the college. As both provost and now president, Sterk has championed the building of stronger connections and more organizational flexibility among the four schools offering undergraduate programs—Emory College, Oxford College, Goizueta Business School, and the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. She’s now joined by Provost Dwight McBride to prioritize new teaching pedagogies and ways of learning.

In this atmosphere, new majors and approaches are being encouraged that reflect the changing times and interests of faculty and students. The newest major approved by the college, starting spring 2018, is public policy analysis, a joint program between the Department of Political Science and the new kid on the block, the Institute for Quantitative Theory and Methods (QTM). Launched in 2014, QTM and its associated major have become a national model in helping students gain data analysis skills and apply them to any area of study across the sciences and humanities (see sidebar).

Nearly a third of Emory College students double major, with some pairings clearly complementary and others inviting more creative crosstalk. In fall 2017, the college created a joint degree for a popular double major, the growing area of Spanish and linguistics. There also is a new BS in applied math and statistics, a joint BA in Spanish and Portuguese, and three new programs in physics: physics for life sciences, biophysics, and engineering sciences, which replaces the previous major in applied physics. For a traditional engineering degree, students can still enroll in the dual- degree program with Georgia Tech.

Taking It Global

Emory College student Reilly Dugery 19C kicks off the discussion of office culture by confessing her bafflement that supervisors don’t see email as the formal communication she does.

Nisaa Maragh 19C notes that workers stand out in her office when they dress professionally, since casual is the order of the day. Linguistics professor Susan Tamasi lets other students chime in before she explains office hierarchy and generational difference as cultural components in the work world.

She ends the day’s Intercultural Discourse class by telling her students to continue their ethnography as a way to hone the skills needed to navigate that world. Then Tamasi gets back to work in her Emory office, as Dugery does the same in a Dublin coffee shop and Maragh returns to her Toronto job.

This is the academic portion of Emory’s Global Internship Program, which places thirty undergraduates with companies worldwide and serves as a model of how Emory conducts online classes.

The program, which grew out of a hybrid structure of online and study abroad program development, stands apart from many online college offerings because it demonstrates how a liberal arts education can translate into the workplace. Student interns meet regularly online to apply what they’re learning with other members of the class in a real-time environment.

The exchange among students and instructors can be just as rigorous as in the classroom: instructors interact during discussions and can privately message students.

“One of the biggest questions in the liberal arts focuses on what it means to be part of a culture,” says Tamasi, professor of pedagogy and chair of linguistics. “This online component is how I can connect their experiences in their new cities and in their offices to the theoretical framework of exploring a different culture.”

“The online forum allows me to continue to share my opinion as frequently as I want, yet I hear more perspectives than usual,” Maragh says. “The level of discourse is elevated by the experiences each student shares.”

Group Chat: Quantitative sciences majors and students gather to crunch some numbers.

Big Data, Getting Bigger

“Big data” has graduated from a buzzword to an expanding field of expertise, and job recruiters across industries are looking for data-driven people with critical thinking skills to staff up their departments.

Emory’s Institute for Quantitative Theory and Methods (QTM) is partnering throughout the college and university to help meet this demand. The mission is simple: To embed cutting-edge data science skills into an elite liberal arts education. The institute’s curriculum is accessible to students with a wide variety of academic interests and mathematical backgrounds.

The institute supports the Quantitative Sciences (QSS) major with sixteen tracks, a joint major in Applied Math and Statistics, a new joint major in Public Policy Analysis, and a pending QSS secondary major for business schools students. QTM’s partnerships allow the 150 enrolled students to specialize in areas such as English, psychology, sociology, economics, biology, women’s gender and sexuality studies, and Latin American and Caribbean studies.

“The obvious partnerships, like economics, political science, and biology, are going to be immensely valuable,” says Clifford Carrubba, director of the Institute for Quantitative Theory and Methods in Emory College and chair of the political science department.

“But I think the humanities partnerships will lead to some of the most creative opportunities.”