Coda: Grady Made

If only Grady Memorial Hospital had elevators that worked, internal medicine residency would take two years instead of three. That was my recurring thought as I joined the 7:00 a.m. crowd gathered in silence, listening for a familiar mechanical whir, placing wagers on the next set of opening steel doors. I was on call and, out of habit, running a bit late.

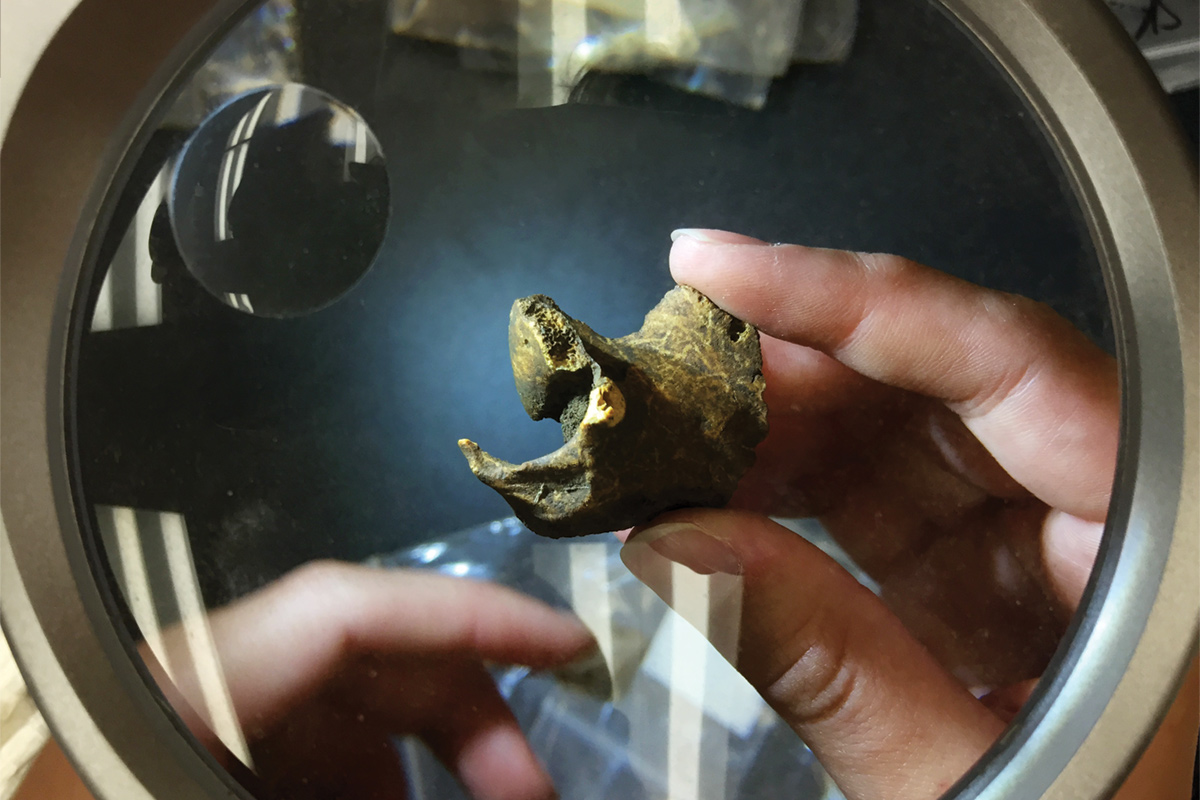

Like moon phases and ocean tides, the call cycle was a geologic phenomenon that dictated my daily life. Today was long call, which guaranteed a fresh onslaught of new admissions from the ER. It was anyone’s guess what cases would land on Grady’s doorstep, but it was a sure bet that I’d see something I hadn’t encountered before. The large county hospital was fertile ground for both rare diseases (e.g., pure red-cell aplasia) and rare presentations of common diseases (e.g., euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis). Even at the end of my first year, I was but a newborn learning to see the world through Grady’s eyes.

To a layperson’s eyes, the hospital might seem like a curiously vintage place. The marble corridors take on a jaundiced hue beneath a layer of dust. Doctors carry clip-on plastic pagers that appear to belong to the 1990s. An intercom system crackles overhead—playing a lullaby for each birth of a “Grady baby” and blaring a panic alarm for each cardiac arrest. The stark juxtaposition of life and death is not lost on me.

Being a “Grady baby” is a declaration that’s at once proud and defiant. The latter is on display even through the thickest encephalopathy; “where are we” and “what year is it” are standard mental orientation questions, but “who’s the president” and “who won the Super Bowl” turn out to be better metrics of sarcasm than delirium. This is especially true for the octogenarians whose medical records read like biographies. As I was welcoming one such patient to my primary care clinic, she reminded me flatly she’d been coming here for ages, having gone through countless iterations of the fresh-faced Emory resident. Like all those before me, I began to recognize Grady for what it was—a de facto cornerstone of an enduring community.

Being a Grady doctor has its challenges, typically in the form of “frequent flyers” and their repetitive rendezvous for using street drugs and never their prescribed ones. Caring for an underserved population can be a lesson in cynicism—until it isn’t. People don’t change—until they do. One attending physician would ask for our “pain score” each morning, a question frequently directed toward patients. The idea that doctors could also have pain was as obvious as it was validating. That awareness would resurface on call days, which were their own patented blend of struggle and triumph.

After one particularly chaotic call day, my team of residents ventured to the rooftop helipad. We planted our feet atop the summit and peered out as the sun sank beneath the concrete canopy of downtown Atlanta. Standing there together seemed to amplify a communal feeling, that working here gave us not only a sense of purpose but also a sense of place. That there were many places to be a patient or be a doctor, but for both parties, there was only one place to be Grady made.

John Chen is a second-year resident in internal medicine with the Emory School of Medicine Residency Training Program.