Experiential Art

Artist Chris Salter 89C blends environment and sensation to create interactive experiences

Anke Burger

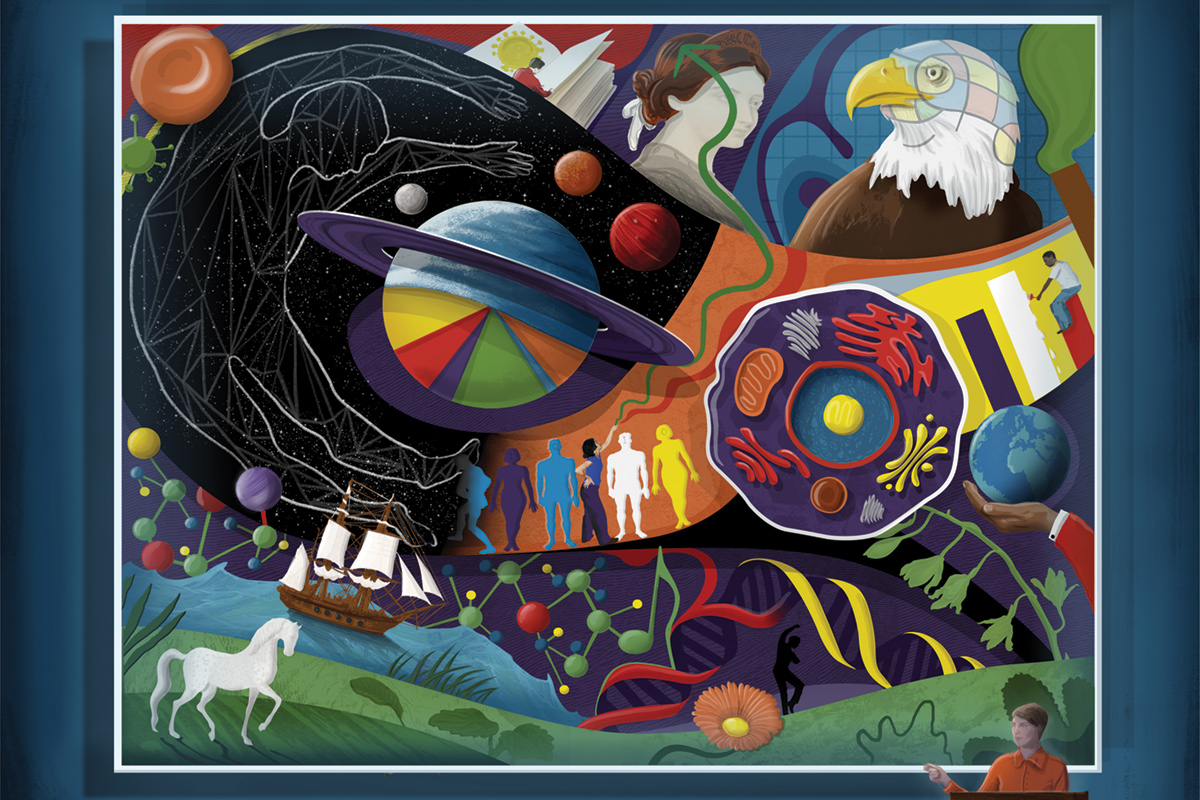

On a summer night in Montreal in the Museum of Contemporary Art, the past and the future are caught in a web of sound and vision: steel cables suspended in the central rotunda and strung with LEDs, flashing to a humming soundtrack being written anew as it plays, driven by an algorithm and sensors throughout the room, a new order constantly in the making. I circle the room for a new perspective, staring up, transfixed: Machine learning can be beautiful.

Tonight is the opening of In Search of Expo 67—a multi-artist homage to Canada’s coming-out party half a century ago. Here at ground zero is N-Polytope: Behaviors in Light and Sound, a project created by Chris Salter 89C and inspired by composer Iannis Xenakis’s installation in the original expo. But Salter has technology at his disposal that Xenakis could only dream of. Which means, like scientists and philosophers grappling with our new creations, he wants his art to answer questions we’ve never quite had to face in the same way.

Salter has a propensity to rattle off the ideas of economists and art historians and philosophers whose ideas are shaping his current work, and when he is in the throes of a project, orchestrating architecture and lighting and programming, he’s positively manic. But tonight in Montreal he is in his element. He is also home—he teaches at Concordia University—though only for a few days: just in from Vienna, where another installation, Haptic Field, was part of the Wiener Festwochen. The day after the Montreal opening, he boards a plane for Berlin, where Haptic Field is about to open at the Martin Gropius Bau, one of the city’s premier exhibition spaces. Berlin is also home for Salter and his wife, translator Anke Burger; they split their time between Germany and Canada.

Once upon a time, Salter wanted to be a lawyer. He arrived at Emory to study economics and philosophy. That he did. But he also discovered theater: the student improv group, directing his own productions, and performing under the guidance of the professional leadership of Theater Emory, which set him on a trajectory exploring performance and technology, a doctorate in theater at Stanford, and onward. (Another little-known fact Salter shares: “Emory was so much more radical than Stanford.”) Not coincidentally, some of the stuff he first waded into in Existentialism and Phenomenology with Professor Tom Flynn at Emory animates the art he makes to this day. “I tell my really good students how lucky we were,” he says. And, like any good artist-educator, he hopes they might feel the same way some day.

The word haptic denotes relating to the sense of touch. And Haptic Field is participatory and immersive: Visitors don clothing and goggles that plunge them into an experience that blurs senses of touch, vision, and hearing. You are aware of others in the room, but in a dreamlike fog. “You can see, but you can’t really see,” Salter says. Fundamentally, the encounters become about touch.

“I wanted to know: Can we share touch?” Salter says. “It’s a complicated phenomenological question.” This convergence of art and science tries to answer that.

While Salter calls two cities home, every other week there’s a good chance he’s headed off to work on another project: in China or Australia or India or France or Japan. But as Haptic Field takes form in Berlin, his perspective is tempered by the wisdom of fifty years. “In the past I would have had a nervous breakdown,” he says. “Now my assistant does that.”