State of Mind

New book explores the notion that racism is a mental illness

Ann Borden

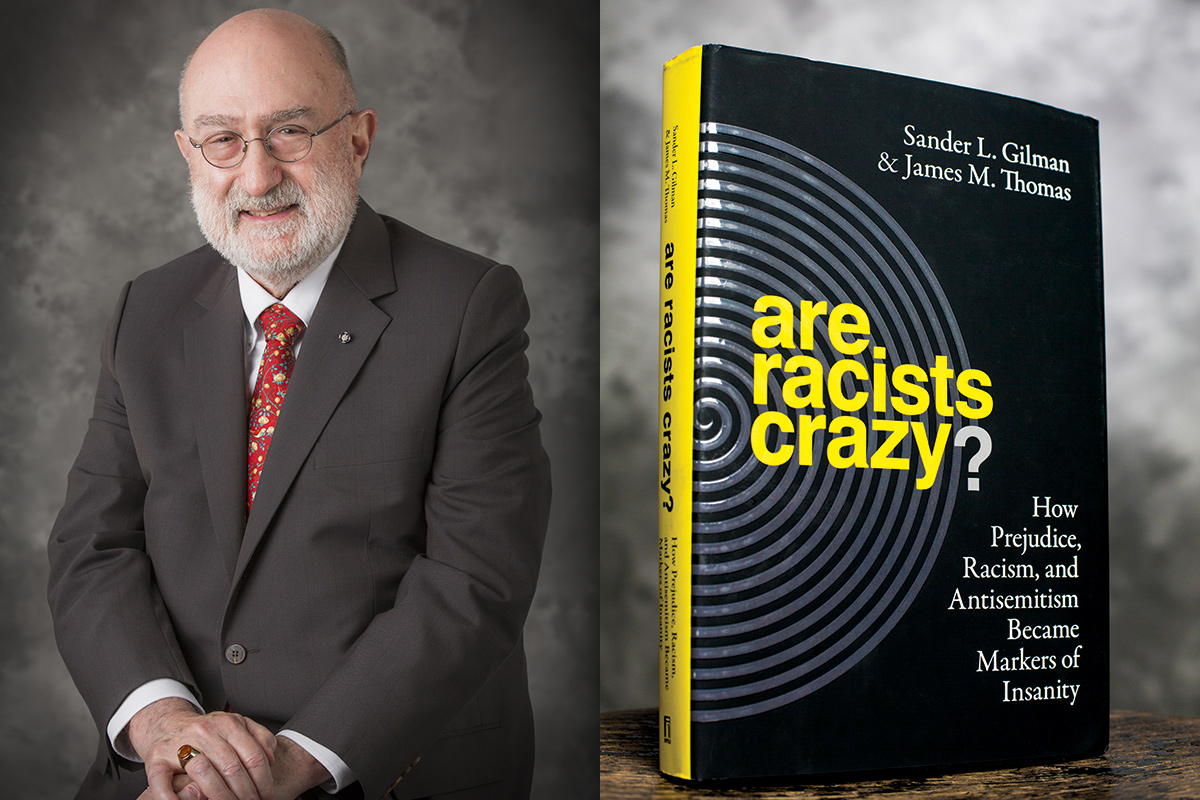

Sander Gilman, Distinguished Professor of the Liberal Arts and Sciences and professor of psychiatry, is an intrepid cultural historian with more than seventy volumes to his credit—including Seeing the Insane and Jewish Self-Hatred.

His tenure at Emory began thirteen years ago with the publication of Fat Boys: A Slim Book, and he has since authored or edited more than twenty books and been honored as a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Last year, Gilman teamed with James Thomas, a sociologist at the University of Mississippi, to write Are Racists Crazy? How Prejudice, Racism, and Antisemitism Became Markers of Insanity—part of a provocative new series by New York University Press.

During a drive to a conference at the University of Mississippi, Gilman and Thomas discovered that they “shared a deep interest in the difficulty and complexity of thinking about race and psychopathology as a cultural problem, indeed as a litmus test for our complicated understanding of race, racism, and mental illness,” Gilman says.

In the book, the two men describe a 2012 experiment at Oxford University—a randomized, double-blind experiment in which researchers administered a beta-blocker to one group while the other received a placebo. Both then completed the implicit association test, whose score “refers to how fast a person matches certain words or images to evaluative concepts (e.g., white people/good, black people/bad).” Those taking the betablocker demonstrated lower levels of subconscious racial bias.

The “pill-for-prejudice study” scored mass media attention. Alarmingly, the subsequent conversation revolved around how, and when, a medical “cure” for racism would be available. Ignored, say Gilman and Thomas, was whether the study had appropriately conceptualized racism’s scope and scale.

Then, in a 2015 Dutch study, researchers claimed to have removed phobic responses—in this case, to spiders—through the same beta-blocker. But, as Gilman and Thomas ask, “Should the overall claim of the Oxford study now be understood as arguing that racism is really merely a phobic response to an imagined terror that can be cured through the application of a drug and reexposure to its cause?” In other words, is all we are lacking a public health model that could target antisocial behavior as it had targeted infectious diseases?

Gilman and Thomas also touch on the legal arena, pointing out that “for more than thirty years, there has been a legal precedent for recognizing racism as a delusional disorder, allowing perpetrators of racially targeted violence to evade justice for their actions.”

Beginning in mid-nineteenth-century Europe with antisemitism, Are Racists Crazy? jumps the pond to the US and proceeds to the present day, all in the service of understanding how racism became a mental illness. For Gilman and Thomas, racism “can manifest itself as a symptom of an individual’s disease process,” but ultimately it is a political phenomenon.