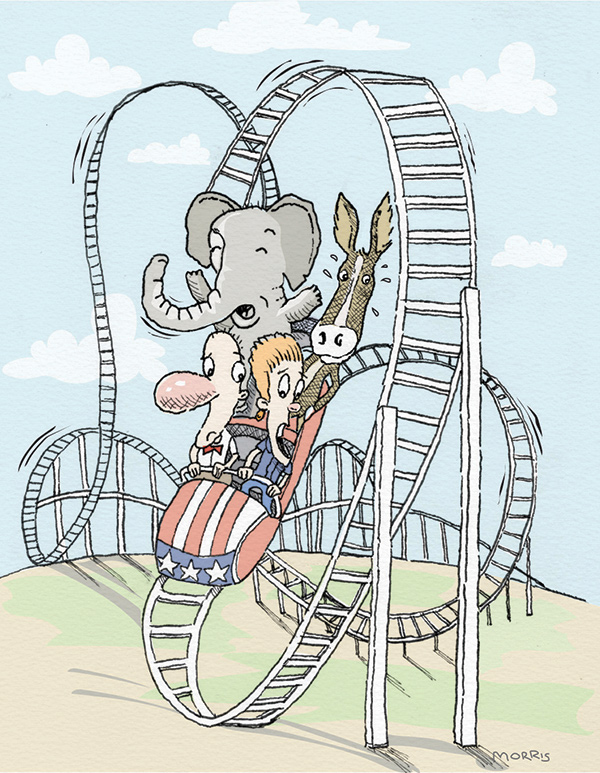

Wild Ride

Don Morris

Whether you've relished each twist and turn or are desperately wishing it would just be over, it's clear that the 2016 presidential election will go down as one of the most interesting in US history. Emory's political experts have been busy sharing their expertise in the national media and attempting to explain how US politics got us to this point and what might happen next.

Here are four ways they believe the 2016 presidential election is breaking the mold.

Time for change? Wait for the ‘But’

Alan Abramowitz, Alben W. Barkley Professor of Political Science, is one of the most respected presidential poll forecasters in the country. His “Time for Change” model has correctly and precisely predicted the popular vote winner within two percentage points or fewer since 1988. In this fall’s election, his model predicts a narrow win for Donald Trump, based on a variety of factors. “The model is based on the assumption that the parties are going to nominate mainstream candidates who will be able to unite the party, and that the outcome will be similar to a generic vote, a generic presidential vote for a generic Democrat versus a generic Republican,” Abramowitz told Vox. “That’s usually a reasonable assumption and produces pretty accurate predictions.” But Abramowitz believes his model is wrong this year. Trump is definitely not a typical, mainstream Republican candidate, and it’s debatable whether he has united the party. Reasonable assumptions just don’t work, says Abramowitz, and “It would not shock me if he ends up losing.”

Median voters rebel

In political science, there’s a widely accepted theory, called the Median Voter Theorem, which states that an outcome selected by majority rule will select the outcome preferred by the median voter. As a result, moderate candidates for president typically beat candidates considered ideologically extreme by voters.

That’s how US elections generally play out—but not this year. Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science, told NPR that one of the most interesting things about this year’s election is that very few predicted Trump’s primary win over more moderate and established Republicans. So how did the political pollsters and academics miss that Trump was preferred by the median voter?

“I don’t think anyone thought that Donald Trump would appeal to the median GOP voter, much less the general election voter. But now we have to consider that. This will necessarily prompt how we measure voter attitudes, particularly how we identify the attitudes that influence vote choice,” Gillespie says.

Rollercoaster polls

Presidential election polls have always vacillated, but seldom so wildly as during the 2016 race, and the media have covered every bump of the ride.

But these polls don’t paint an accurate picture of voter preferences, wrote Abramowitz with coauthor Norman Ornstein in The New York Times.

“The problem is that the polls that make the news are also the ones most likely to be wrong. And to folks like us, who know the polling game and can sort out real trends from normal perturbations, too many of this year’s polls, and their coverage, have been cringe-worthy,” Abramowitz wrote.

“Smart analysts are working to sort out distorting effects of questions and poll design. In the meantime, voters and analysts alike should beware of polls that show implausible, eye-catching results,” he added.

The First Gentleman

Bill Clinton’s role as the first-ever male spouse for a US presidential candidate (and his possible role as the first husband to a president) is truly unique and very important, wrote Gillespie for The New York Times.

"I know Hillary Clinton has said that her husband will not be picking china patterns, but he should do just that and more."