My Left Hand

Orlando college student receives first hand transplant in Southeast at Emory

A few weeks Ago, Linda Lu pulled a water bottle out of the refrigerator and automatically used her left hand to steady it while she unscrewed the cap with her right. She paused, looking startled.

“That’s the first time I’ve done that,” she said.

In March, Lu became the recipient of the first hand transplant in the Southeast, performed at Emory University Hospital.

Her left hand was amputated before she was a year old due to Kawasaki disease, an autoimmune condition that can restrict blood flow to limbs. The twenty-one-year-old Valencia Community College student had heard about Emory’s hand transplant program and, after some Internet research, decided to send an inquiry to hand transplant surgeon Linda Cendales. “I sent her a really vague email at three a.m., and she responded with a beautiful essay and called me the next day,” says Lu.

Cendales, the only surgeon in the US with formal training in both hand microsurgery and transplantation, says many potential transplant patients contact her directly. “Everyone has different circumstances, and every email is a personal email, so I individualize each email back,” she says. “It’s one of the great privileges I have.”

Because hand transplant surgery is optional—a matter of quality of life rather than life or death—and because the recipient must take immunosuppressant drugs, it is still a rare and carefully considered practice. “We use a very thorough screening protocol,” says Cendales, assistant professor of surgery. “It’s a relationship from both sides. We’re learning about the candidate and the candidate is learning about us.”

Lu traveled to Emory for evaluation and underwent days of physical and psychological testing before being accepted as a candidate and placed on the waiting list for a donor in early November 2010. “I told my parents, and they were overwhelmed with happiness at the possibility,” she says. “But I really don’t think I’d have gone through with it if not for Dr. Cendales and the fact that she’s so qualified.”

Cendales’s interest in hand transplantation was piqued through her experiences observing the hands of patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis in Mexico City, where she went to medical school. “I wondered if an alternative option would provide better results,” she says. “These patients were already on immunosuppressant drugs, so that wouldn’t be an additional risk factor for them.”

In 1999, Cendales helped to organize the team that conducted the nation’s first hand transplant in Louisville, Kentucky. “He’s doing very well,” she says of the recipient, Matthew Scott, who recently spoke at Emory at the tenth annual meeting of the International Hand and Composite Tissue Allotransplantation Society.

After furthering her training with transplant and research fellowships at the National Institutes of Health, Cendales came to Emory in 2007 to establish the Emory Transplant Center’s hand transplantation program and refine the technique that made Lu’s surgery possible.

Lu’s hand transplant on March 12 was the first in the Southeast and the fourteenth in the nation. The nineteen-hour operation involved two teams: one focusing on Lu, the other on the donor arm. The teams combined about a third of the way into the surgery, connecting first bone, then soft tissues, then, under a microscope, doing the intricate work of joining vessels and nerves. Revascularization—when blood flows through the newly joined vessels into the attached limb, giving it a healthy glow—is a remarkable moment, says Cendales.

Near midnight, the surgery was complete. “When I woke up, they told me it was successful. I could tell they were exhausted but excited,” Lu remembers.

Woodruff Health Sciences Center CEO S. Wright Caughman said Lu’s surgery was a truly multidisciplinary endeavor. “The transplant team included scores of Emory Healthcare staff, multiple surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, operating room and rehabilitation staff,” he wrote in a letter to the Emory community. “We came together to achieve something few have ever done before.”

Cendales says the team also included members from LifeLink; Yerkes National Primate Research Center; the Atlanta Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VA); orthotics, prosthetics, and rehabilitation services from Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta; Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute; and “half of Emory University Hospital.”

She and Lu both expressed deep gratitude to the anonymous donor’s family for their generosity.

As director of Emory Transplant Center’s Vascularized Composite Allotransplantation (VCA) program and Laboratory of Microsurgery, Cendales is a pioneer in this emerging field. VCA focuses on developing and refining the transplantation of multiple tissues (skin, muscle, bone, cartilage, nerve, tendon, and blood vessels) as a functioning whole, as well as managing the risk of rejection.

Working with Yerkes, Cendales has studied forearm tissues after transplantation in rhesus monkeys, seeking to improve post-transplant drug regimens. “Like any other transplant, the body will tend to reject a hand transplant,” she says. “Recipients must be on immunosuppressant drugs for as long as they have the transplant.”

VCA is an emerging specialty around the globe, with recent transplants involving donor faces, knees, tracheae, and even a uterus. Cendales’s research is sponsored by a Department of Defense grant and is conducted in partnership with the Atlanta VA, since it holds great promise for soldiers who lose limbs.

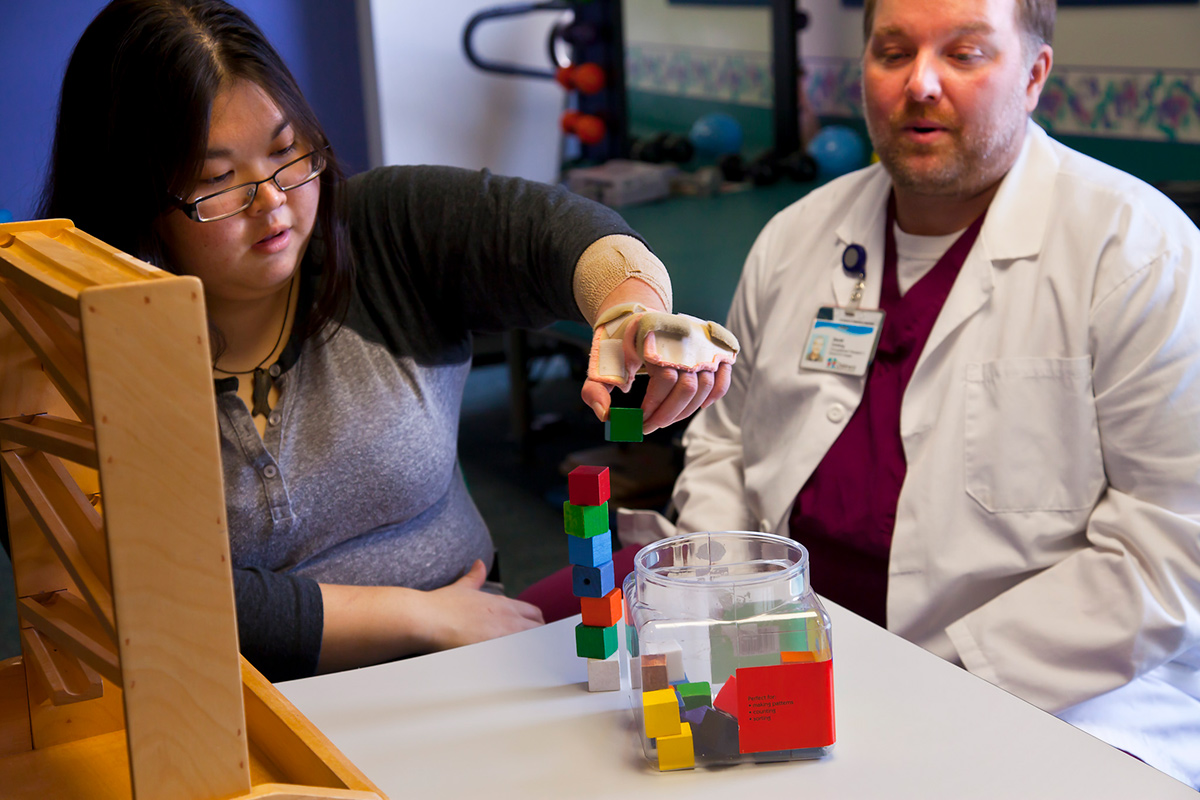

Lu is staying at the Carlos and Marguerite Mason Guest House at Emory’s Clairmont campus while she receives therapy and says the experience so far seems “surreal and magical.” Her left hand has no sensation yet, but she can move it, pinch her fingers together, and stack blocks. Her brain is adapting to learn to command the new limb. “When I was in elementary school, I was fitted with a prosthetic hand several times. They felt more like a nuisance than anything else and never lasted more than two or three weeks,” she says. “But this already feels like my hand. My hope is that eventually I’ll be able to include it into daily functions without being paranoid or overly protective.”

Recently, Lu was walking through the hospital with her left hand in a brace. “Someone walked by and said, ‘Hey, I feel your pain, I broke my thumb last year.’ I just smiled.”