An Unlikely Education

Why a school in the middle of nowhere means the world to its students

In 2006, Jonathan Starr 99C’s office overlooked a bustling Harvard Square. The twenty-seven-year-old founder of a hedge fund in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he was a precocious overachiever in one of the world’s most lucrative industries—a talented analyst with a six-figure salary and a bright future in finance.

Now, were it not for the nine-foot security wall, the view from his new office in the Maroodi Jeex region of Somaliland would stretch unbroken over a camel-colored moonscape traversed only by turbaned nomads and the occasional troop of baboons.

Off to the left, he would see the aptly named village of Abaarso (Somali for “drought”) with its roadside stalls selling groceries and khat, the psychotropic shrub chewed by the vast majority of Somali men. And farther on, the capital, Hargeisa, home to approximately 1.3 million people, among them the president of the breakaway republic, which won its independence from Somalia in 1991 and has been vying for recognition ever since.

The wall, though, is necessary.

So too are the armed guards that patrol it with their Kalashnikovs and two-way radios, holdovers from the Somali Civil War. Because inside, Starr is conducting an experiment in education: he wants to find out what happens when you immerse Somalia’s brightest boys and girls in a “culture of English” with plenty of books and calculators and a staff of dedicated teachers from some of the best schools in the world.

Abaarso Tech, the nonprofit educational organization Starr cofounded three years ago, is designed to be run like a business, with Somalis as shareholders and customers. The school’s hundred students pay what they can, while several revenue-generating programs—adult English courses, a school of finance, and an executive MBA track—make up the shortfall. And this is where the former financial executive has most pointedly parted ways with convention, bringing a level of accountability to development work that its critics have long found lacking.

“What if Marriott operated without any revenue, room rate, or other meaningful customer-usage data from its individual hotels?,” Starr asked readers of the Wall Street Journal in an op-ed he penned for the paper last April. “Suppose it remitted money to cover salaries and other expenses without knowing if any of it was producing a product for which customers were willing to pay? . . . You don’t have to run a Fortune 500 company to know how quickly such a system would run amok.”

Yet, he wrote, when it comes to international aid, that’s precisely the system in place. Lacking quality customer-satisfaction metrics, nongovernmental organization (NGO) executives can’t know whether employees on the ground are providing valuable services to their impoverished “customers.” And that, Starr feels, is because those executives aren’t on the ground themselves.

Starr didn’t say anything that hasn’t been said before—most notably by the former World Bank economist and author William Easterly, a vocal critic of international aid. But unlike most, he has put his money where his mouth is: more than half a million dollars in donations to the school and more than $200,000 in noninterest loans.

And his commitment goes beyond dollars. Starr spends one month a year in the US, most of it in his hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, where his mother, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, still lives.

For the other eleven, he resides in the middle of what might plausibly be described as nowhere—or as the British once called it, the Furthest Shag of the Never-Never Land: a parched patch of earth in a country that doesn’t officially exist in a region best known, if at all, for its piracy and poverty, its droughts and famines, and the seemingly intractable civil conflict that rages on between the forces of the Western-backed Transitional Federal Government and the violent Islamist rebel group, Al-Shabaab.

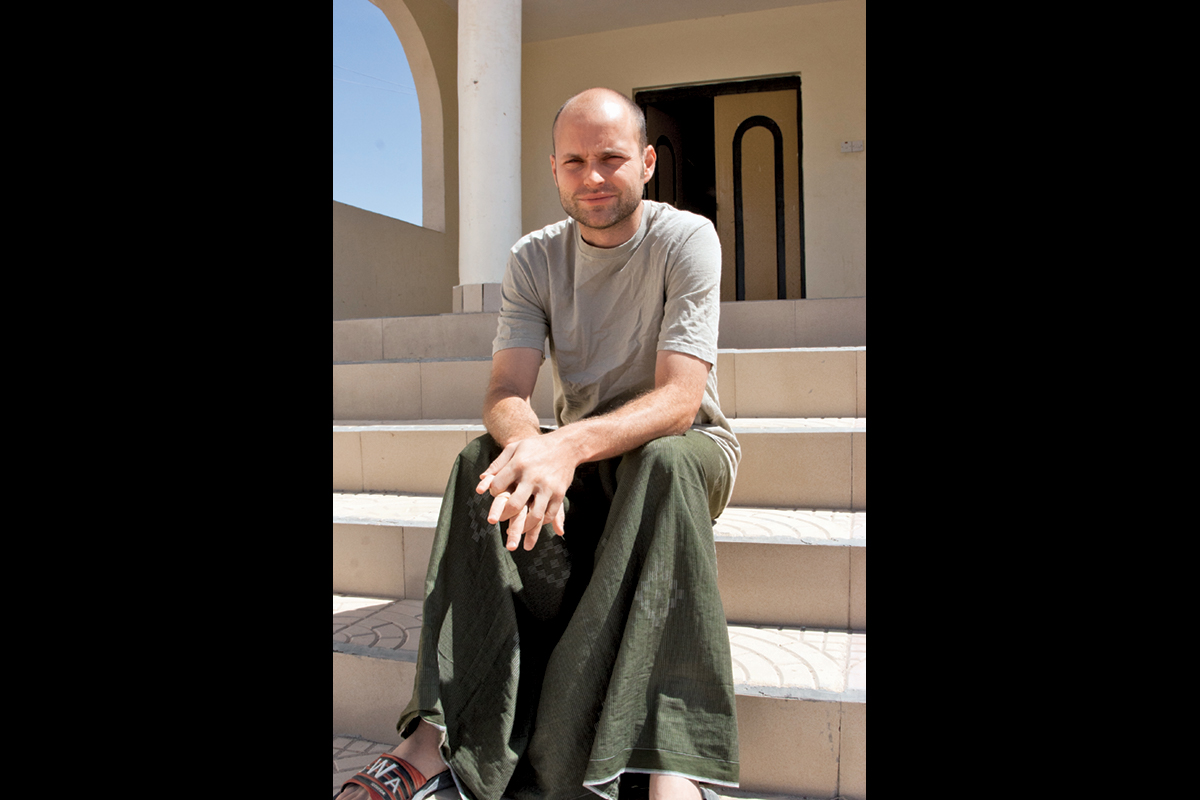

I’m a capitalist,” Starr told me as we took a tour of the campus on a blustery morning last March. I had arrived the night before on a flight from Dubai, the third leg of a roughly twenty-four-hour journey, and when I found him the next day, he was sitting in the school’s communal kitchen, swatting flies and rubbing the sleep out of his eyes over a bowl of cornflakes.

“And as much blame as Wall Street gets, I don’t agree with it,” he said. “I think it plays a vital role in society, and I think one reason the American system developed far better for two centuries than the rest of the world is that it had a much more efficient capital market that looks at a business and says that it shouldn’t get funded anymore.”

Few people would look to the international aid community for a Wall Street apologist. But then few people could imagine an aid worker like Starr, who, in his tattered T-shirt, flip-flops, and macawiis, the traditional sarong-like kilt favored by the more conservative of Somali men, seems to revel in upending stereotypes.

Before he founded Abaarso Tech, Starr knew next to nothing about running a school. He didn’t know much about Somaliland, either. What he did know he had learned from his uncle, Bille Osman, a native of the country and a former employee of the United Nations who emigrated to the US in the 1960s.

“He would mention things now and then,” recalls Starr, “About growing up there and what that was like. So I had always been curious.” Moreover, after five years at the helm of a hedge fund, he had had enough of finance. “I was obsessed with it,” he says. “I couldn’t help but spend every minute of my time thinking about it. And I wanted to be obsessed with something else. I wanted to do something very different.”

In 2007, Starr closed the firm and made his first visit to Somaliland, joining Osman on a kind of needs assessment with a focus on education, particularly at the secondary level. The war, he learned, had devastated the country’s infrastructure, including many of its schools. And perhaps none had been a greater loss than Osman’s own alma mater, the once-renowned Sheikh Secondary School.

Founded by the British when Somaliland was still a protectorate of the crown, Sheikh was for many years the country’s premier prep school and a veritable pipeline to higher education abroad. It produced many current Somaliland leaders, including the president, H. E. Mohammed Mohamoud Silvano, and several members of his cabinet.

But Sheikh is no longer what it was. Abandoned after the war, it was closed for more than a decade before being reopened by an Austrian charity in the late 1990s. Then, in 2003, the school’s headmaster and his wife, both highly regarded educators, were gunned down by members of Al-Shabaab. Ever since, Sheikh has struggled to recruit teachers, and only a handful of graduates have gone on to universities overseas—none of them in the US.

If terrorists succeeded in crippling the country’s best school, Abaarso Tech, which aims to prepare students for top-tier institutions in the US and UK, represents a kind of reprisal—led by the largest group of Americans in the entire region: a collection of twentysomething college graduates with sterling resumes and advanced degrees and the ability to command far higher salaries than any Starr can offer.

Nevertheless, they came, and they continue to come, and as all of them will tell you, the job is not for the faint of heart. Teachers at Abaarso Tech work, on average, seventy-hour weeks. They forgo showers when the water is low, and alcohol, which is illegal in Somaliland, for semester-long stretches. They eat the same seven meals every week, “burger night” being the unanimous favorite, and they do it all for approximately $3,000 a year.

And this, Starr believes, is how it should be.

While other Western-led efforts to educate poor African children have spared no expense—Oprah Winfrey’s $40-million Leadership Academy for Girls in South Africa features, among other extravagances, a yoga studio and a beauty salon, and the manager of Madonna’s recently aborted $15-million all-girls’ academy in Malawi made what auditors described as “outlandish expenditures on salaries, cars, and office space,” according to the New York Times—Starr economizes wherever possible.

“I began with the precept that our employees’ principal form of compensation would be pride in a worthy deed well done,” he wrote in the Journal. Citing the sluggish deployment of aid dollars in Haiti, he argued that generous pay is not only unnecessary for success in development work, “it is counterproductive.” Absent accountability, he added, “highly compensated individuals will choose the path of longest-term funding over good solutions.”

And here, too, Starr has led by example. “I make negative,” he told me as we walked from the kitchen, with its single stovetop and broken refrigerator, past a sandy soccer field and along a low stone wall hand-built by students who, for some infraction or another, had pulled hard labor with Tom Loome, a twenty-seven-year-old math teacher from Minneapolis and the school’s tireless handyman.

“If I were personally making big money on this, I think it would be much harder to get the caliber of teachers we’ve had so far,” he says. “But the fact is that everyone comes because they’re committed to the cause, and that makes a big difference.”

Of course, it’s one thing to make a financial sacrifice. It’s another to educate Somali girls and boys in the shadow of an Islamist rebel group with the stated aim of overthrowing the government and imposing its own strict version of Islamic law on the general population.

Al-Shabaab (the name means “youth” in Arabic) has claimed overt affiliation with Al Qaeda and declared war on the U.N. and Western NGOs, killing forty-two relief workers in the past four years. While the group isn’t welcome in Somaliland, it has been known to enter uninvited—such as in 2008, when it detonated bombs in the Ethiopian Embassy, the headquarters of the United Nations Development Program, and the presidential palace.

Last November, Starr and staff received an urgent message from British Embassy officials in Djibouti: Al-Shabaab, they learned, had identified Abaarso Tech as a target, and an attack could be imminent. That night, an emergency meeting was convened to review the school’s security as well as what the staff would do when and if the shooting began.

In the days that followed, extra ammunition was purchased for the guards’ guns, new protocols were established for night patrols, and one teacher terminated his contract and returned home. The rest of the teachers stayed on. They were rattled, they said. Who wouldn’t be? But they weren’t about to leave—not now. (No attack occurred, Starr adds, and the alert was likely based on faulty intelligence.)

“Even those who volunteer at Abaarso Tech do so with mixed motives,” Ken Menkhaus, a professor of political science at Davidson College and an expert on Somalia, told me when I asked him for his thoughts on the school and Starr’s rather unflattering account of NGOs in the Wall Street Journal. “They are gaining valuable experience that they can parlay into better-paid jobs later. I do not accept the dichotomy of selfish versus altruistic motives.”

Still, it was hard to see how any teacher weighing the risks could have decided that staying was worth it—particularly in light of the murders at Sheikh. “Didn’t you even consider going home?” I asked Loome, the math teacher from Minneapolis, who was one of Starr’s first hires after he founded the school. The answer was no.

At the time, I didn’t believe him. And then I met Maaria.

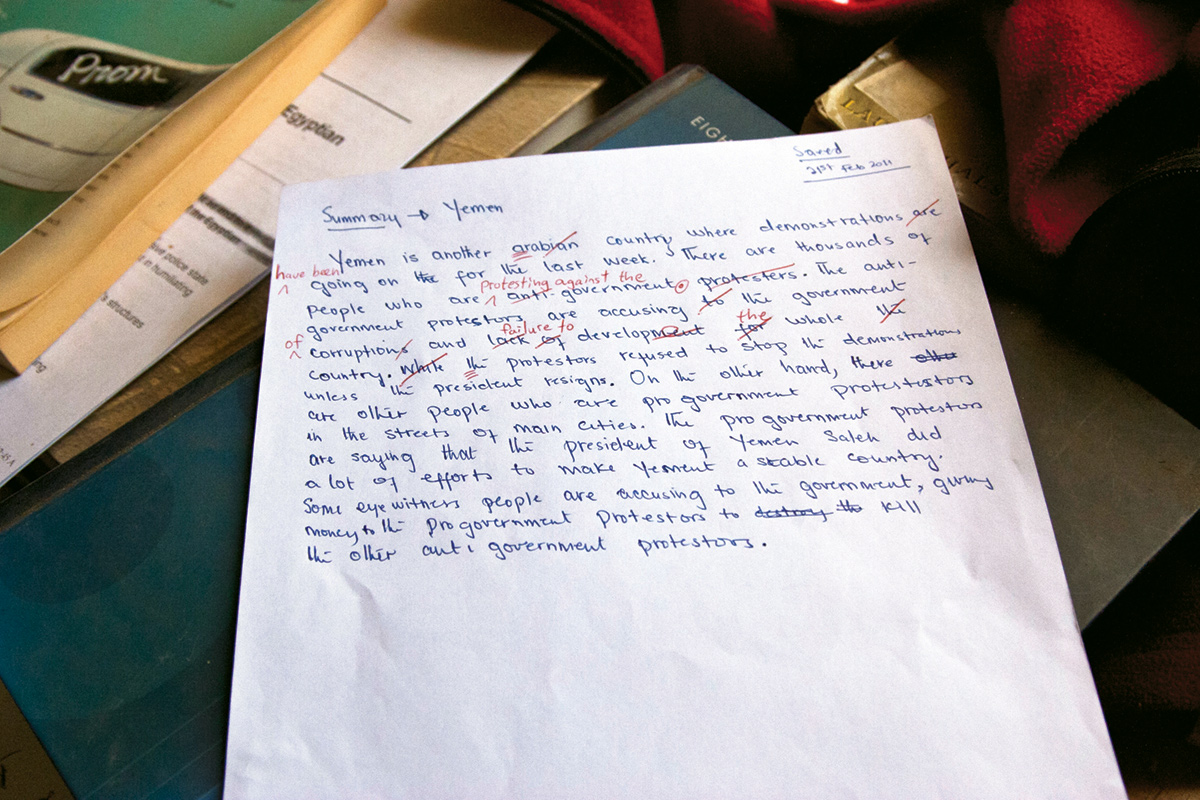

Maaria Osman is small and slight, with hazel eyes and a round face framed by a tight-fitting hijab, the traditional head cover worn by women throughout the Muslim world and by all female teachers and students at Abaarso Tech. Shy and reserved, she speaks softly in halting English. She is not yet fluent in the language.

Yet at twelve, Osman is one of the best math students in the school. Last year, she had the highest score on the math section of the national exit exam, the test administered to all eighth-grade students around the country in the last days of what is, for the vast majority of Somali students, their final year of formal education.

That Osman even took the exam was unusual. According to a recent survey by UNICEF, only slightly more than a quarter of Somali girls of primary school age are enrolled in school. That figure is attributable in large part to the collapse of the central government in 1991 and the decades of conflict that ensued. But the biggest obstacle to Somali girls’ enrollment, says UNICEF, is the tendency of mothers to keep their daughters home to share the burden of domestic labor.

For all of their daughter’s ability in the classroom—her uncommon facility for multiplying fractions, for instance—Osman’s parents had just such a plan in mind. The eighth grade was to be their daughter’s last. It wasn’t that they weren’t aware of Abaarso Tech or the fact that Osman could attend the school for free, as many students do. It was that her curricular achievements were immaterial to the family’s immediate needs. They declined his invitation.

But Starr persisted. Enlisting the help of some of his best female students and their mothers, he mounted a recruiting strategy worthy of a Big Ten football program. And at last, the effort paid off.

In the eight months since her arrival, Osman has exceeded expectations. Not only has she outperformed many of her peers—including a handful of diaspora students from the US and UK—she’s exhibited a work ethic bordering on obsession.

“She does math problems in her spare time,” Mike Freund, a math teacher from Illinois and the director of the undergraduate finance program, told me. “Literally every night, she’ll finish her homework and come to me to ask for more. She’s incredible. But she does have a pretty hard time dealing with it when she gets one wrong. That’s something we need to work on.”

It may be that Starr saw in Osman a bit of himself—the diligent student at Emory, where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and graduated summa cum laude in economics. By twenty-five, he’d become the youngest analyst at a prestigious New York hedge fund and had even managed to write a book—a primer on value investing, the philosophy first championed by the legendary analyst Benjamin Graham.

“He was fanatical about investment philosophy, and he’s fanatical about what he’s doing now,” says Anand Desai, a friend and former colleague of Starr’s on Wall Street, who has donated generously to the school. “He’s got this idea, this vision for the school, and he’s completely thrown himself into it. He’s become a student of Somaliland, because what drives him is being right by the reasoned approach.”

For Hodan Guled 04MPH, a Somali refugee from Mogadishu, Starr has served as an inspiration. In 2008, Guled founded S.A.F.E. (Somali and American Fund for Education) with the goal of improving access to education for Somali youth by strengthening the capacity of the country’s existing schools, primarily through capital improvement projects.

“I was always looking for a way to give back,” she says. “Somalia needs so many things. And I realized, for its long-term growth, education is the most important thing we can invest in. If people are educated, they can think beyond the clan rivalries. And they can both get and create jobs.”

Several months ago, Guled returned to Somalia for the first time since 1993, when, as a twelve-year-old, she fled the country with the rest of her family.

“We got on one of the last flights out,” she recalls. “We were very lucky.”

In addition to visiting friends and relatives, Guled stopped by Abaarso Tech to meet Starr and to see with her own eyes the biochemistry lab built partly with a donation from S.A.F.E.

“Abaarso Tech was our first school,” she says. “At the time, we didn’t have a process for identifying schools, and I read about Abaarso in the Emory Wheel. So I contacted Jonathan. I remember he was so passionate, so enthusiastic about it. And I thought, wow, he lives there. That’s impressive.”

On a Friday morning last march, Starr stood before an auditorium packed with guests of the first annual Abaarso Tech Open House. Pacing the stage in khaki pants and a freshly ironed button-down, he told them about new projects under way: the wind turbine that would reduce the school’s dependence on diesel generators; the $65,000 mosque currently under construction; and the decision by the College Board, publisher of the SAT, to begin the process of recognizing Abaarso Tech as the country’s first official test center.

And then he moved on to the feature presentation: the Best Student competition. The winner, he said, would spend one year at Worcester Academy, the private coed boarding school in Massachusetts that Starr himself attended as a kid.

“This was an extremely difficult decision,” he said. “Our four finalists are all outstanding.” But the previous week’s practice SAT exam had put one candidate ahead of the pack.

Mubaraak Mahamoud, everyone knew, was the smartest student in school and one of the most mature. A native of Hargeisa, he grew up in an Ethiopian refugee camp before making his way back to his hometown. When Mahamoud first arrived, he spoke no English at all. No one could have predicted how quickly he would excel. “He just dominates in the classroom,” says Harry Lee, Abaarso Tech’s dean of students and head basketball coach. “He also works extremely hard and has a great attitude. All the boys look up to him.”

“Mubaraak has done something few American students ever do,” Starr told the room. “He scored a 710 on the math section of a practice SAT exam. That is actually higher than the average score on math for incoming students of MIT.

“Congratulations, Mubaraak, you’re going to America.”

And with that, the room erupted, and Mahamoud was carried out on the shoulders of his cheering classmates into the blinding light of the Somali sun.