The Sweet Sight of Success

Joseph Skibell's new novel features eye doctors, people with vision who can't see, and Sigmund Freud, who (to the distress of many) may be omniscient

Kay Hinton

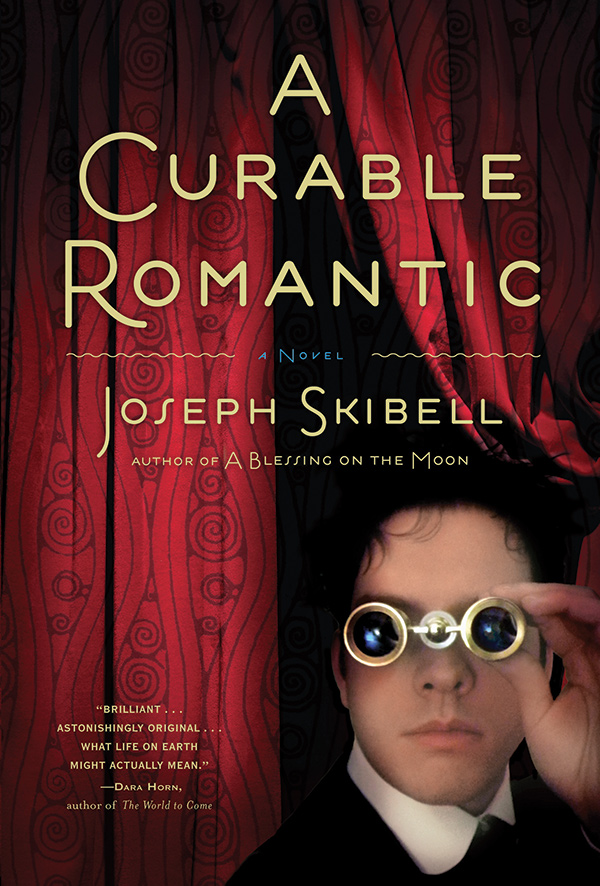

A Curable Romantic By Joseph 608 pp.; Algonquin Books $26.95

Joseph Skibell is a keen follower of novels’ first lines, so I must go for broke in my opening: “Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned, nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.” William Congreve, meet Skibell, author of the ambitious third novel A Curable Romantic, due out in paperback in November. In May, the Jewish Book Council awarded the book the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature Choice Award, which carries a prize of $25,000.

More about the woman wronged follows, but first to Skibell, who has been a member of the Department of English and the Creative Writing Program at Emory since 1999. Last year, for the first time, he led the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature as it brought Margaret Atwood to campus for a series of talks. (The quality of this highly regarded series is expected to continue with the prolific David Mamet, who has agreed to appear in 2012.)

A Curable Romantic is big in size but, more important, in scope. The novel may represent, though, Skibell says ruefully, “the last opportunity to write a big book.” What sort of writer gets to usher out something so long beloved? The key has been in taking risks, in doing projects that interest him.

After graduating from the University of Texas at Austin in 1981, Skibell earned an MFA from what is now called the Michener Center for Writers. There, he produced the short-story version of what would become his first novel, A Blessing on the Moon (1997)—a work that won the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation Award and the Steven Turner Prize for First Fiction.

The novel was gutsy; Skibell talks about violating the gentleman’s agreement not to fictionalize the Holocaust. Nevertheless, his family—which lost eighteen loved ones to the atrocities—supported the book. When Skibell went back to the book in 2009 in order to write the libretto for Andy Teirstein’s opera version of it, he says that he “was impressed by how fearless I was as a young novelist. I don’t think I’d have the courage to write that book now.”

If not courage, the current book has demanded other kinds of equally estimable skills: for instance, establishing a mood for three very different sections and imposing exacting historical fidelity. After all, as the dust jacket states, the novel’s axis is nothing less than the “life, times, and loves of Dr. Jakob Sammelsohn, a fairly incurable romantic wandering optimistically through modern history.”

It is peopled with historical characters: Sigmund Freud; his real-life patient Emma Eckstein; Dr. Wilhelm Fliess (with whom Freud conducts a bromance); the founder of Esperanto, Ludwig Zamenhof; and Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of the Warsaw ghetto.

In Skibell’s book trailer, he calls A Curable Romantic “the most passionate writing experience” he has had. One might think the genesis for the novel was the lurch between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as the world moved away from religion and toward science. Though that is a significant part of the book, Skibell confesses that he wanted to write about Freud since he was “a failed screenwriter.”

A Curable Romantic received three starred prepublication reviews (from Publishers Weekly, Booklist, and Library Journal) and was named best novel of the year by Atlanta Magazine. It was featured in the Denver Post, the San Francisco Chronicle, Parade Magazine, the New York Times, Jewish Ideas Daily (as one of the “best Jewish novels of the year”), and the Independent Booksellers Association. Skibell is also nominated for Georgia’s Author of the Year Award.

Readers sometimes have objected to the book’s part three, which may be because it takes them to less familiar, more challenging places. A review in the New Yorker read: “Skibell depicts fin-de-siècle Vienna with energy, but . . . a final section set in the Warsaw ghetto resolves the plot’s supernatural elements at the expense of a more fundamental coherence.”

Skibell could choose to be offended. He worked hard on the history and then traveled to Europe to be sure he got it right. He even taught himself Esperanto.

But, there is the consolation of simply having a review in the New Yorker, which not many writers can claim. And the good reviews—heaped as high as hay after the harvest—have not stopped. Esther Schor, writing in the New Republic, notes: “It’s a high-energy, wild performance, as ample as its protagonist’s appetites—the postmodern Jewish novel as a mashup of genres: Yiddish folktale, sentimental education, Freudian case history, erotic confession, utopian parable, all wrapped up in an ‘alternative history’ of Jewish emancipation. . . . And toward the end, the novel becomes a metaphysical jeu d’esprit that is perversely naturalistic, superbly comic, and in the bargain, heartrending.” Take that, New Yorker.

As promised, we must return to A Curable Romantic’s wronged woman. Her name is Ita. That is all I will say, except that her considerable capacity for revenge propels this daring novel.

As the author of one of the world’s last big books noted, “Well do I remember the day that Ita started talking.” It was off to the races from there.