Kicking Grass

How Atlanta's rebooted pro team is bringing soccer back

Leigh Friedman 03C doesn't have six arms. It only looks like it.

The director of marketing for the Atlanta Silverbacks, the city's reborn men's professional soccer team, spends home games at field level. While the players battle on the pitch and the scoreboard, she stage-manages the rest of the game experience. Friedman emerges from under the stands every few minutes, often carrying something different than the time before.

One time, it's a stack of red Silverbacks jerseys; another it's Silverbacks scarves, which the players eventually hurl into the stands. She guards the microphone for guests who deliver the halftime announcement, and has been known to sling laptop cases over each shoulder—when she isn't toting her red Silverbacks shoulder bag.

The one constant is the clipboard storage case riveted to Friedman's hand. It's packed with everything necessary for a smooth evening at Atlanta Silverbacks Park: media notes, game notes (the mini-programs handed out to fans), team rosters, a stadium map, league operations guide, game timeline (which lists the schedule of PA announcements and contains information on a variety of featured guests, ranging from the anthem singer to the face painter near the concession stand), scissors ("because you never know," Friedman says), Sharpies, pens, business cards, a flash drive, extra media credentials, and a ponytail holder (an underrated tool for any professional woman on the go).

With just ten full-time staff, working for the Silverbacks means job descriptions are flexible.

"You could ask any one of us a question about anything, and we'd be able to give you an answer because we've probably done it at one time or another," says Friedman, who tends to smile when she speaks. She previously worked as a regional marketing director for ESPN Zone restaurants before joining the Silverbacks on January 3, just six weeks after the team rebooted and only three months before the start of the 2011 season. Most franchises have years to prepare before stepping onto the field.

The Silverbacks last suited up in 2008. Never a moneymaker, when the economic downturn hit in earnest the team was placed on indefinite hiatus by its owners. In sports, as in most anything else, "indefinite hiatus" is a synonym for "death sentence." Once teams go away, they don't come back.

But professional soccer in the US isn't like other sports. With more false starts and backfires than a 1971 Pinto, pro soccer's development has been unconventional and, more often than not, disappointing. The Silverbacks had always wanted to return but weren't quite sure how. In 2010, interest in minor-league soccer swept through Atlanta—this time, in a good way. When the smoke cleared, the meetings adjourned, and the lawyers and bankers closed their briefcases, the Silverbacks found a new life in a new league, with Emory alumni leading the charge at nearly every level.

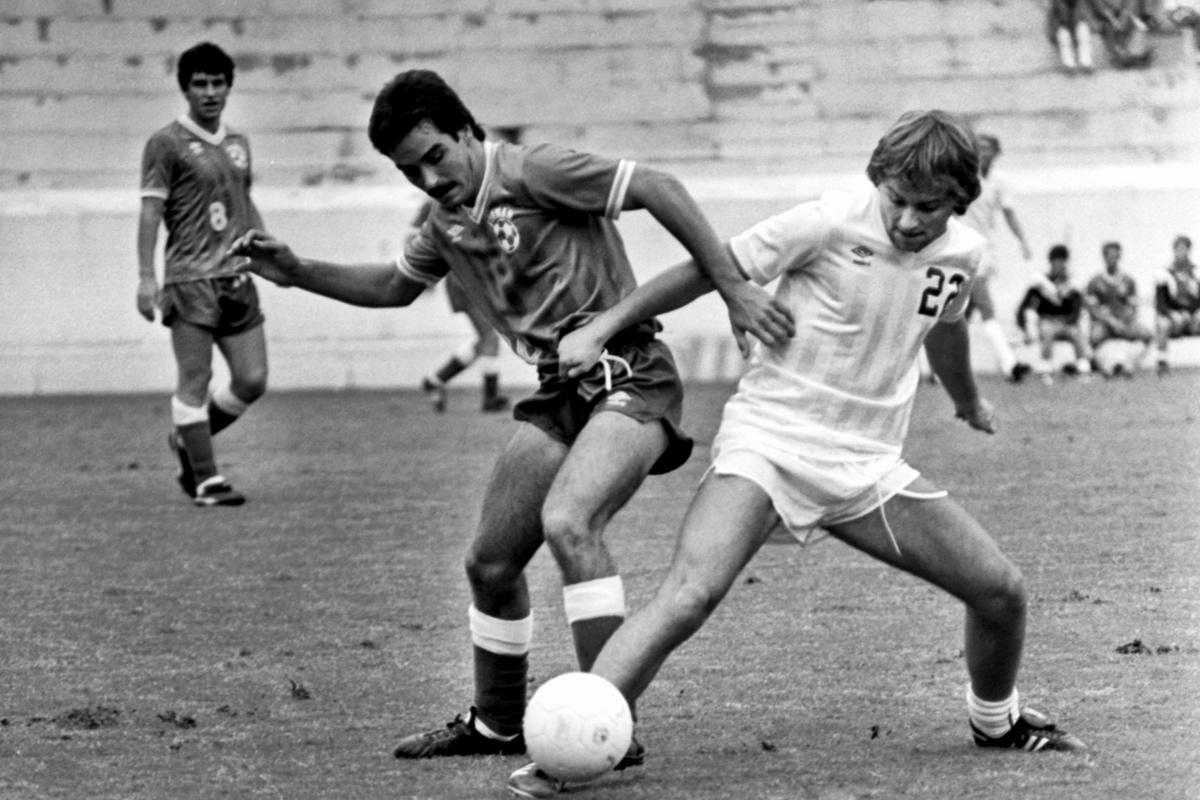

The Atlanta Silverbacks emerged in 1998 from the wreckage of the Atlanta Ruckus, then a member of what was called the A-League—at the time, US soccer's top minor league (also known as "second division"). That year—one in which the team finished a less-than-stellar 7-20, played to sparse crowds at Adams Stadium off North Druid Hills Road, and suffered a league-mandated takeover—John Latham 79L, a partner at the Atlanta law firm Alston and Bird, received a call from his biggest client, sports apparel company Umbro.

Umbro had promotional interests in the league, and its representative informed Latham that the Ruckus owner had defaulted on his obligations, resulting in the takeover and a clunky midseason name change to A-League Atlanta. The company might litigate and it asked Latham to be prepared.

But before the conversation ended came the big question: Did Latham know anybody who might be interested in taking over the franchise?

"I mentioned this to my good friend, Bobby Glustrom," Latham says. Glustrom was a law partner and is a former adjunct professor in the Emory School of Law. "The next thing I knew, we were the owners of a soccer team."

The team wasn't A-League Atlanta for long. Before they took the field for the 1999 season, the franchise was rechristened the Atlanta Silverbacks, their logo featuring a stern-looking silverback gorilla modeled on Zoo Atlanta's most famous nonhuman primate resident, Willie B. They also moved home games to DeKalb Memorial Stadium in Clarkston, which was slightly better than Adams, though not much.

Latham knew the legal twists and turns of the sports business, so he knew he couldn't go it alone as an owner. The Silverbacks organization faced many challenges—it was a minor-league team in a major-league city packed with sports franchises, limited revenue streams, and a less-than-ideal home venue.

Latham needed a major investor. He eventually found one.

In 2001, technology entrepreneur Boris Jerkunica 87C 87G bought the site of an old drive-in movie theater on the southeast corner of Spaghetti Junction in Atlanta. His idea was to build a multiuse park centered on his favorite sport.

When his parents immigrated to Atlanta in the 1970s from Croatia (then part of Yugoslavia), the young Jerkunica brought his love for soccer with him. He joined the Emory soccer team in 1983, and in 1987 he graduated as its greatest player. Nearly twenty-five years after his last game, Jerkunica remains Emory's all-time leader in goals (sixty-one) and assists (fifty-three). Jerkunica also led the Eagles to two NCAA tournaments. It's a record that earned him election to Emory's Sports Hall of Fame in 2002.

"Boris made everybody better," says Jerkunica's former Emory coach, Tom Johnson 62G, professor of health and physical education. "He was a leader, but not a 'rah-rah' type of leader. He led by example. And he walked to his own beat."

Dissatisfied with DeKalb Memorial Stadium, Latham learned of Jerkunica's project and contacted him. The two men hit it off personally and professionally. What resulted was a deal that would eventually move the team to the park once the stadium was complete. The park would be named for the Silverbacks, and Jerkunica purchased a stake in the team while Glustrom stepped away.

Jerkunica also worked out regularly with the Emory men's soccer team. There he met midfielder Michael Oki 03B, one of the team captains. They kept in touch, and following Oki's graduation, Jerkunica hired him to handle his business affairs, including those related to the Silverbacks. As the park took shape, Oki's responsibilities there increased, and he eventually began managing the $18 million facility exclusively.

The twenty-acre park is centered on the five-thousand-seat pro stadium, easily expandable to 7,500 and more if needed. The Silverbacks arrived in 2006, but even without them the park stays busy, hosting soccer and kickball leagues every night. Emory's soccer teams practice there before road games on field turf.

The park is the epicenter of the Silverbacks organization, which is bigger than just the flagship men's professional squad. The Atlanta Silverbacks Reserves are a men's developmental team that plays in the National Premier Soccer League (NPSL), a fourth division league.

There also is a women's professional squad, aptly named the Atlanta Silverbacks Women, that plays in the W-League (women's pro soccer's second division). Unlike the men's team, the women's squad never suspended operations (Latham was the driving force behind their continued existence and remains heavily involved today), and the Silverbacks Women have won four consecutive division titles.

As the Silverbacks men find their footing, Oki has emerged on the leadership side. He now serves as the team's president, leading the day-to-day operations, and is the only staff holdover from the old organization.

"This is only the beginning for us," says Oki, who shares his boss's energy and forward-thinking vision. He also shares Jerkunica's drive. Oki needed it to build an organization from scratch, which included signing more than twenty players and a coach, readying the park for the grind of a long season, relaunching the brand, and recruiting a staff to get it all done between Thanksgiving and the first week of April—on a limited budget.

"You need to get down and get your hands dirty," Oki says. "I'm happy for what we've done in a short period of time, and I'm very excited for what we can do. I consider it a mini-success. But it's not the end game."

"You've got to be young at heart," Jerkunica adds. Now in his mid-forties, a little heavier than his playing weight and his close-cropped hair a lot grayer, Jerkunica still gives off the impression that he could school a much younger man on the soccer field. Much of that energy probably comes from keeping up with his two young daughters, both under age three. He exhibits a blend of intensity, confidence in his people, and a laid-back personal style.

Professional soccer has a lackluster history in the US and the Atlanta market. While millions of kids (and adults) play recreationally around the country, that participation has never translated into mainstream success beyond a small (but passionate) fan base. Recent years, though, have shown some improvement.

Major League Soccer, the league at the top of what's called the US soccer pyramid (the sport's domestic infrastructure), is a solid contributor to the country's sports landscape. But the Silverbacks' level, the second division, has long been on shaky ground. The latest effort to bring some stability is a new league with a familiar name, the North American Soccer League (NASL).

"Aaron Davidson is the guy who was instrumental in making the NASL happen," Jerkunica says of the league's chairman of the board. "Without Aaron, the NASL would not be here. Period."

In 2006, Traffic Sports USA bought a soccer team, and the guy they asked to run it was Aaron Davidson 93C.

Traffic Marketing Esportivo, based in Brazil, bills itself as a soccer event management company, one of the largest in the world. Traffic Sports USA is its American arm and Miami FC, as the team was known, was Traffic's first venture into team ownership. Following Miami FC's first year in the United Soccer Leagues (USL), the Traffic brass wasn't impressed.

"Our president looked at me and said, 'Aaron, you're a lawyer. You've been around long enough,' " says Davidson, now president of Traffic Sports USA. He was charged with leading Miami FC and helping restructure the league.

Davidson's move began a multidimensional chess match for control of the second division that lasted the better part of four years. It came to a head in 2010 when relations among league owners, which were now split into two groups—one of them led by Miami and calling itself the NASL, the other comprising USL loyalists—got so bad that the United States Soccer Federation (USSF), the sport's domestic governing body, took the second division over and separated the factions into conferences.

Around that time, in mid-2010, Davidson met a young lawyer in New York. Rishi Sehgal 02C had been working in Brazil, but was looking for new options. Davidson offered him a role in building the new league.

Sehgal was heavily involved in the NASL's 2010 application for second division status—the true breakaway from the USL. After a few false starts, the USSF approved provisional sanctioning for second division status for the NASL.

"When you wake up thinking about it and you're doing it all day and you go to sleep thinking about it, then you have a dream about it, you start to wonder when the day ends and the next one starts," says Sehgal of the work necessary to acquire sanctioning. He now holds the title of the NASL's director of business development and legal affairs. "But it was fun. It definitely pushed me to new levels, which in some respects I didn't know I had."

The new NASL was a go.

The NASL includes eight teams: five in the continental US (the Silverbacks, Carolina RailHawks, Fort Lauderdale Strikers, FC Tampa Bay, and NSC Minnesota Stars), two in Canada (FC Edmonton and the Montreal Impact), and the Puerto Rico Islanders. Its minimally outfitted headquarters on Brickell Key in south Florida overlook downtown Miami. The 2011 season had already started before the NASL acquired a conference table. That's what happens when you assemble a league in less time than it takes spaghetti sauce to go bad.

Sports fans from the pre-ESPN era will remember the old NASL, which existed from 1968 to 1984, as the first attempt to introduce soccer to the US masses. Depending on one's perspective, the league was a noble but well-intentioned failure doomed by overexpansion and overestimation of the country's appetite for a different kind of football, or a still-vibrant brand just waiting for renewal by the right people in the right atmosphere. Obviously, the new league includes many more people who agree with the latter.

The new NASL is performing an interesting balancing act—paying homage to the old league while avoiding its mistakes, as well as the mistakes of the USL. What the league doesn't want is the volatility that has plagued the sport for decades, especially in the second division, with teams bouncing in and out.

The key for everyone involved is a consistent product on the field and good ownership off it. "Our biggest focus is stabilizing the markets we have and growing into other places that are stable. One of the great things about being the NASL is that we come equipped with a history," Sehgal says.

One of the first steps is stability in ownership. Despite the difficulties regarding sanctioning, the NASL appears to be getting there, but with a footnote: the preponderance of Traffic money boosting up the league has got bloggers buzzing about the company's motivation. Davidson has experience refuting the doubters.

"When you start big projects you need a few or at least just one person to believe," Davidson says. "And then you've got to build it. When you build it and more people start believing and are more willing to put money in the league, then you become more independently owned."

Recent decisions refute the notion that the NASL is Traffic's private sandbox. For instance, following the hiring of an NASL commissioner and a Strikers president, Davidson now has just one job, Traffic president. He'll spend the majority of the summer in Argentina, overseeing Traffic's involvement in the Copa América soccer tournament.

"We looked at the markets and wanted to choose one that had second division soccer before," Davidson says of the Silverbacks partnership. "In the case of Atlanta, it was unbelievable. Boris still owned the facility, and he still loved the sport. He no longer wanted to risk 100 percent of his money, but he wanted to come back in and help what he started."

The NASL is preparing for growth. The San Antonio Scorpions are ready to take the field to replace the Impact in 2012. They have a local owner, a stadium, and even a logo. Ottawa joins the league in 2013.

"When it comes to growth, we want to be organic and keep our visions humble," Sehgal says. "We have eight teams in the league in our first year. I don't know what the ideal number of teams to have will be in five years. But it definitely would not be eight."

The new Atlanta Silverbacks debuted on Saturday, April 9, 2011. They lost 2-1 to the NSC Minnesota Stars, but more than 3,500 excited fans were there. Average attendance has dipped to around three thousand, but that still puts the Silverbacks third in the league, despite a seven-game winless streak to start the year.

"When I came around the corner for the first game, I had a tear in my eye," Jerkunica says. "There are all these people here, and they care. They really want to be here. That was the first time I felt that in ten years since I've been involved with the Silverbacks."

Keeping those fans involved is one of the Silverbacks' most important jobs. Friedman and Oki lead the outreach charge, which includes conversations with local Latino communities, youth groups and leagues, and even the Emory community, which can purchase discount tickets.

"Yes, we're smaller, and we're going to have certain challenges, but how often do you go to a Falcons game and you bring twenty kids who get to hold hands with the players as they walk on the field?" Friedman says. "When you come to a Silverbacks game, and you want an autograph from every player, you will get an autograph from every player. They won't leave until you have it."

Silverbacks games don't yet have the raucous party atmosphere you might see at larger venues or in larger leagues, but the loudest group of fans—those with the drums and whistles and flags and other accessories—will stack up their passions against anyone. Not all of their chants are appropriate for a family magazine, but "FC! Willie B.!" is inspired. They even have a nickname, Westside 109, named for the section in which they sit.

"Whether you're the owner, the field manager, the director of marketing, or anyone else in the organization, game day is what we're all working toward every day," says Friedman, who has game days through September 24, perhaps even more should Atlanta make the playoffs. She and Oki both said that while they love the regular season, they are looking forward to the off-season when they will have more time to build the Silverbacks' product, which they had no choice but to fast-track before this April.

"Everything comes together on game day, and win or lose, it's an exciting place to be," she says. "But, of course, it's always better to win."

Eric Rangus is former communications director for the Emory Alumni Association and a writer in Atlanta.

Email the Editor