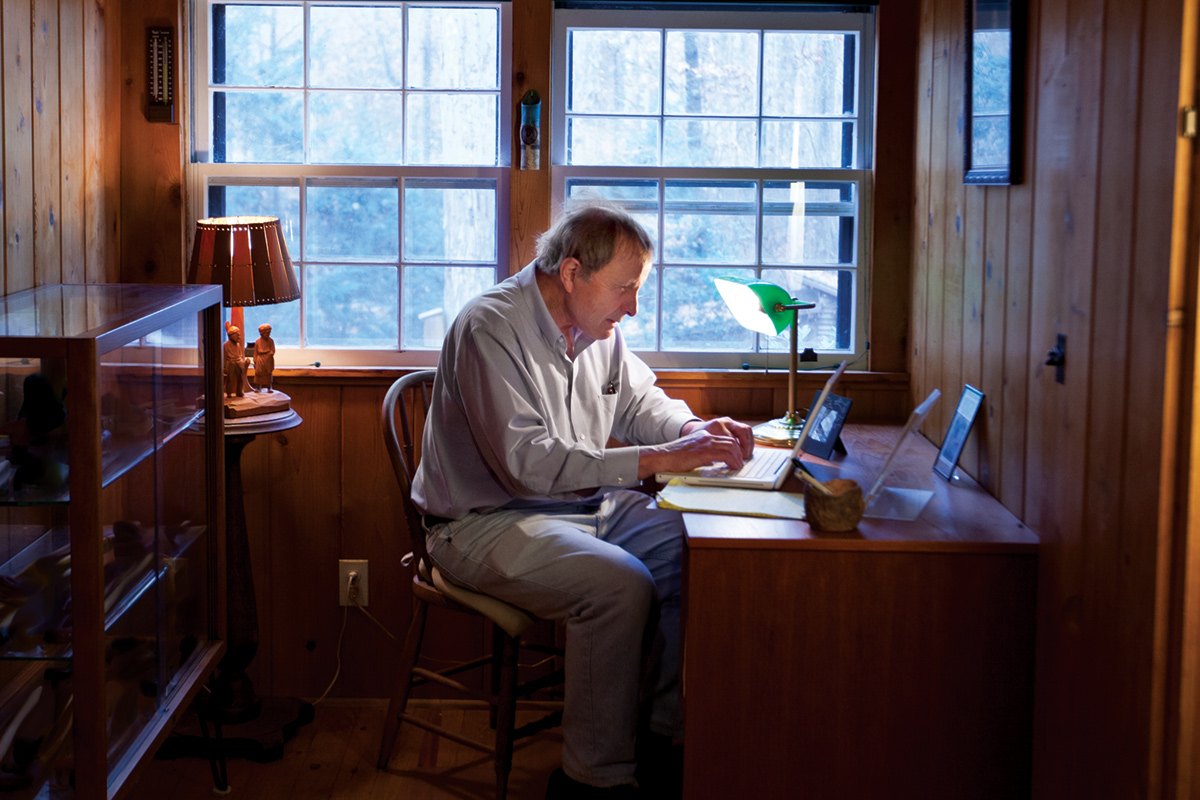

From the President

As American as . . . Compromise

Update from the Editor, February 24, 2013

A number of people have raised questions regarding part of my essay in the most recent issue of Emory Magazine. Certainly, I do not consider slavery anything but heinous, repulsive, repugnant, and inhuman. I should have stated that fact clearly in my essay. I am sorry for the hurt caused by not communicating more clearly my own beliefs. To those hurt or confused by my clumsiness and insensitivity, please forgive me.

For ongoing coverage of developments related to President Wagner’s column on compromise, please visit the Emory News Center.

Original Column

As American as . . . Compromise

During a Homecoming program in September, a panel of eminent law school alumni discussed the challenges of governing in a time of political polarization—a time, in other words, like our own. The panel included a former US senator, former and current congressmen, and the attorney general for Georgia.

One of these distinguished public servants observed that candidates for Congress sometimes make what they declare to be two unshakable commitments—a commitment to be guided only by the language of the US Constitution, and a commitment never, ever to compromise their ideals. Yet, as our alumnus pointed out, the language of the Constitution is itself the product of carefully negotiated compromise.

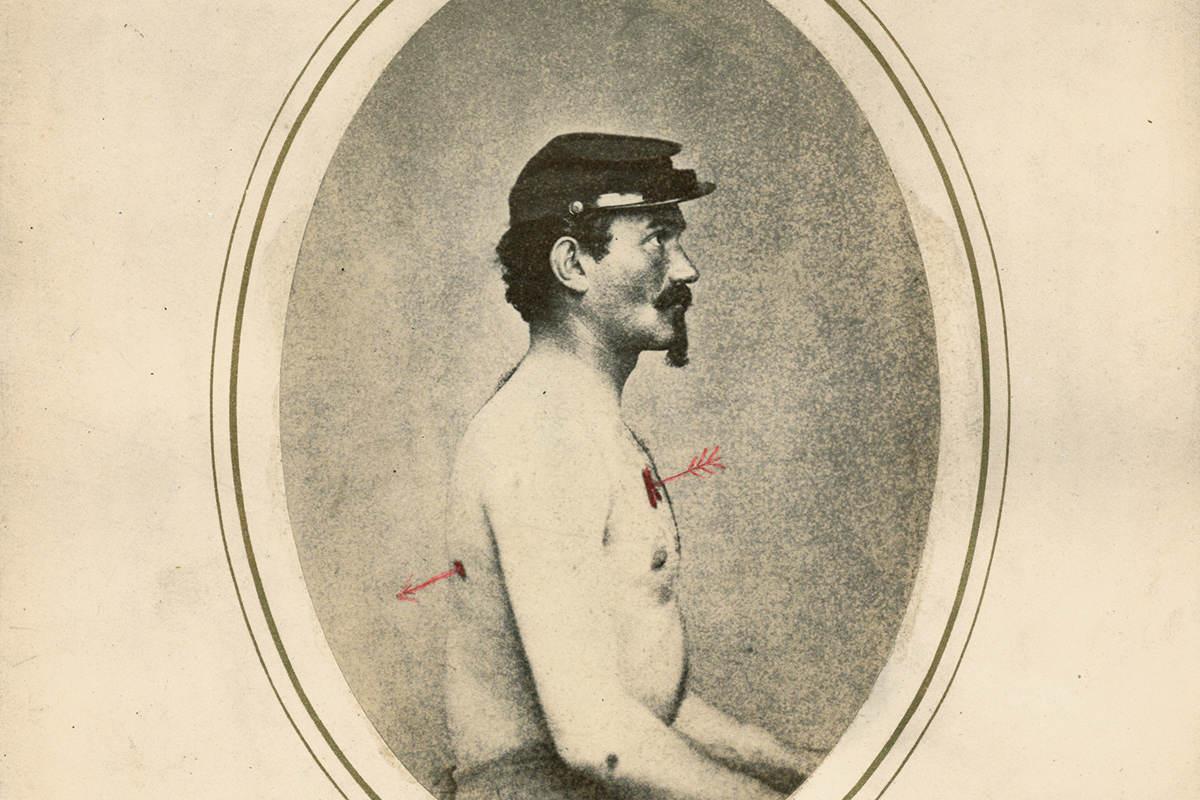

One instance of constitutional compromise was the agreement to count three-fifths of the slave population for purposes of state representation in Congress. Southern delegates wanted to count the whole slave population, which would have given the South greater influence over national policy. Northern delegates argued that slaves should not be counted at all, because they had no vote. As the price for achieving the ultimate aim of the Constitution—“to form a more perfect union”—the two sides compromised on this immediate issue of how to count slaves in the new nation. Pragmatic half-victories kept in view the higher aspiration of drawing the country more closely together.

Some might suggest that the constitutional compromise reached for the lowest common denominator—for the barest minimum value on which both sides could agree. I rather think something different happened. Both sides found a way to temper ideology and continue working toward the highest aspiration they both shared—the aspiration to form a more perfect union. They set their sights higher, not lower, in order to identify their common goal and keep moving toward it.

As I write this, our country’s fiscal conundrums invite our leaders to wrestle with whether they will compromise or hold fast to certain of their pledges and ideologies about the future of our nation’s economic framework. Whatever the outcome of this fiscal debate over the next months or years, the polarization of our day and the lessons of our forebears point to a truth closer to our university.

A university by its inclusiveness insists on holding opposing views in nonviolent dialogue long enough for common aspirations to be identified and for compromise to be engaged—compromise not understood as defeat, but as a tool for more noble achievement. The constitutional compromise about slavery, for instance, facilitated the achievement of what both sides of the debate really aspired to—a new nation.

Something like this process occurs every week on a university campus. Through debate, through questioning, through experimentation, we aim to enlarge the sphere of knowledge and refine the exercise of wisdom, to do the hard work of opening others’ minds and keeping our own minds open to possibilities. The claim is often made that a democratic republic is a highly inefficient form of governance but probably the best we know of so far. The same can be said of a university: its way of discovering and teaching knowledge can be highly roundabout and frustrating, but no one has invented a better way.

Part of the messy inefficiency of university life arises from the intention to include as many points of view as possible, and to be open to the expectation that new ideas will emerge. The important thing to keep in view is that this process works so long as every new idea points the way toward a higher shared ideal, namely truth.

At Emory of late we have had many discussions about the ideal—and the reality—of the liberal arts within a research university. All of us who love Emory share a determination that the university will continue trailblazing the best way for research universities to contribute to human well-being and stewardship of the earth in the twenty-first century. This is a high and worthy aspiration. It is tempered by the hard reality that the resources to achieve this aspiration are not boundless; our university cannot do everything we might wish to do, or everything that other universities do. Different visions of what we should be doing inevitably will compete. But in the end, we must set our sights on that higher goal—the flourishing liberal arts research university in service to our twenty-first-century society.

I am grateful that we have at our disposal the rich tools of compromise that can help us achieve our most noble goals.