At the Corner of Faith and Health

Bridging organizations to create new outcomes

Trey Comstock

Last summer, on the Fourth of July, Trey Comstock 15MDIv 15MPH found himself worlds away from his hometown of Houston, Texas. He was living in rural Kenya in Nyumbani village, a thousand-acre community of about a thousand residents who have lost family members to HIV/AIDS—some nine hundred orphaned children and more than one hundred older adults, all “grandparents,” who care for them.

About the time Houston was preparing for cookouts and fireworks, Comstock was visiting primary schools outside the village, testing the children for malnutrition by measuring the circumference of their arms. He wrote the following post on his blog:

“The work itself is both interesting and heartbreaking. The interesting part is that it is very different from the work that I have been doing so far. Up until now, it has looked a lot like pastoring or being an IT guy. . . . This work represents my first foray into the ins and outs of public health fieldwork. A lot of what one does as a public health professional is gather data to make informed decisions about programs and resource allocation. To me, this is a good lead into my first year at Rollins School of Public Health in the fall.”

Comstock was drawn to Emory specifically for its dual-degree program in theology and public health, a four-year commitment that results in a master’s degree in both fields. The establishment of the program was a joint effort among the Religion and Public Health Collaborative, Candler School of Theology, the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH), and the Interfaith Health Program (IHP). There are only a few such programs in the country.

“A lot of missionaries go out with great intentions, but little training and practical skills,” Comstock says. “I want to work in international missions improving public health, human rights, and social justice as a pastor. Public health is giving me practical, hands-on skills that I can use in a missions context.”

As a field scholar in the RSPH Global Health Institute and a participant in IHP, Comstock joined other grad students for intensive coursework on religion, health, and development in Kenya at St. Paul’s University in Limuru before taking his post at Nyumbani village. There he rebuilt a computer lab, started an after-school program for eighth graders, conducted formal prayer visits with families, and led a worship service for an HIV/AIDS support group.

The relationship between public health and religion is at the heart of the Interfaith Health Program, an initiative that fosters those connections both in the US and abroad to improve health through research, service, and teaching. IHP was originally the vision of Emory Presidential Distinguished Professor of International Health William Foege, former director of The Carter Center, where in the 1980s he enlisted President Jimmy Carter to help launch the program and forge new collaborations across health and faith organizations. In 1999, IHP moved its home base to Rollins, with close ties to Candler, the Department of Religion of Emory College, and the Graduate Division of Religion in the Laney Graduate School.

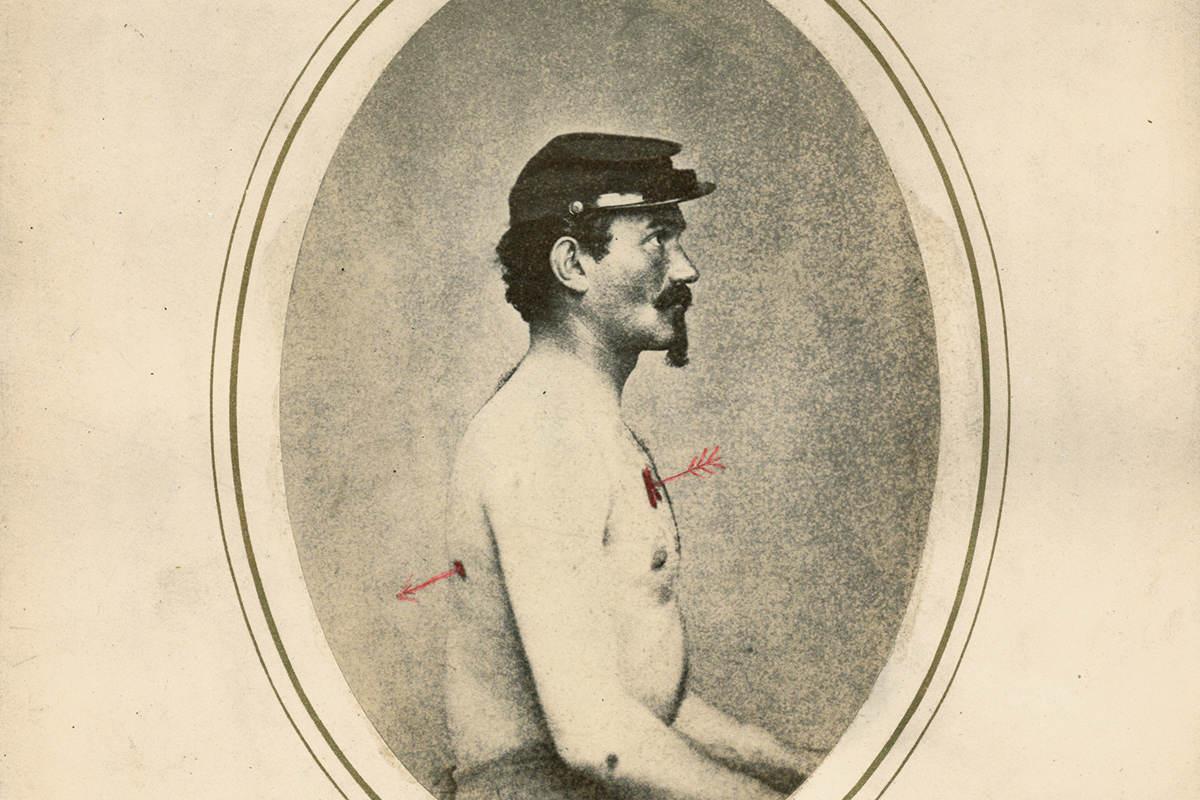

Sandy Thurman

Bryan Meltz

“IHP focuses on the intersection of faith and health, looking at what’s going on in the world and where there are opportunities for faith-based organizations to mobilize and address public health needs in communities,” says program Director Sandy Thurman, who joined in 2008. “We are looking for the right fit for us. Where is it that our skills can be helpful? How can we reach the people who are hardest to reach? The established relationships of trust that faith-based organizations have are what allow us to reach those most vulnerable.”

Mimi Kiser, associate director of IHP, has been with the program since the beginning. She says the successful outcomes of IHP and efforts like it have led to faith-health collaborations becoming more established.

“There is a trend in public health, for a number of reasons, to look beyond the traditional boundaries of public health structures to other partners,” she says. “In the past ten years, the resources for public health have diminished considerably, which has forced a strengthening of ties with other sectors. There is an emphasis on activating faith-based community networks that serve populations not likely reached by mainstream services.”

IHP works to address a range of public health issues, but Thurman brings special expertise to one of its major targets: HIV/AIDS. In the 1990s, she worked with Foege at The Carter Center and also served as executive director for the leading nonprofit AID Atlanta. In 1997, President Bill Clinton appointed Thurman as the director of the Office of National AIDS Policy or “AIDS czar.”

The complex relationship between churches and the AIDS movement—particularly in the African American community, where homosexuality is more likely to be frowned upon—makes the disease a perfect testing ground for a program like IHP.

“What we have seen are two sides of the coin,” says Thurman. “Faith-based organizations in the past and even currently have been part of the problem, but we have also found that they can be part of the solution. They stepped up to respond to the AIDS epidemic before many governments responded. I’ve seen that both overseas and right here in Atlanta.”

When he finishes his Emory degrees, Comstock hopes to work in communities affected by HIV/AIDS in East Africa—where, as Thurman points out, faith-based programs provide a large percentage of health care services and are among IHP’s “best partners.”

“I’d like to help the church find ways to reduce the stigma, to talk about prevention and treatment, the risk in marriages,” Comstock says. “Faithfulness is within the church’s wheelhouse to talk about.”