As Good as Dead

Ethics Center symposium takes on the zombie apocalypse

Scott Garfield/Courtesy of AMC

Mindless, shuffling eating machines. Decomposing corpses who walk the earth. Boney bags of instinctive id.

Zombies are making a comeback—which is, after all, what zombies do best.

According to scholars and fans who gathered at Emory’s Center for Ethics on October 31 to attend the Halloween symposium “Zombies and Zombethics,” these cannibalistic creatures represent everything from the threat of pandemic infections to symbolic sacrilegious resurrection to fears of fundamentalist zealotry.

“What is it about zombies? They are mindless, focused on consumption, single-minded but not conscious, not really malevolent, just hungry,” said ethics center Director Paul Root Wolpe, introducing a panel discussion on AMC’s hit series The Walking Dead, largely filmed in Georgia.

“We are alive. The zombies are dead. And yet, we can kill them. So what are we doing? We’re killing death,” Wolpe said. “There is great satisfaction in that. In a subliminal sense, we’re defeating death.”

The symposium raised perplexing quandaries: Do zombies have free will? Would it be ethical to place zombies, or those who are bitten by zombies, in quarantine? How does the zombie brain work?

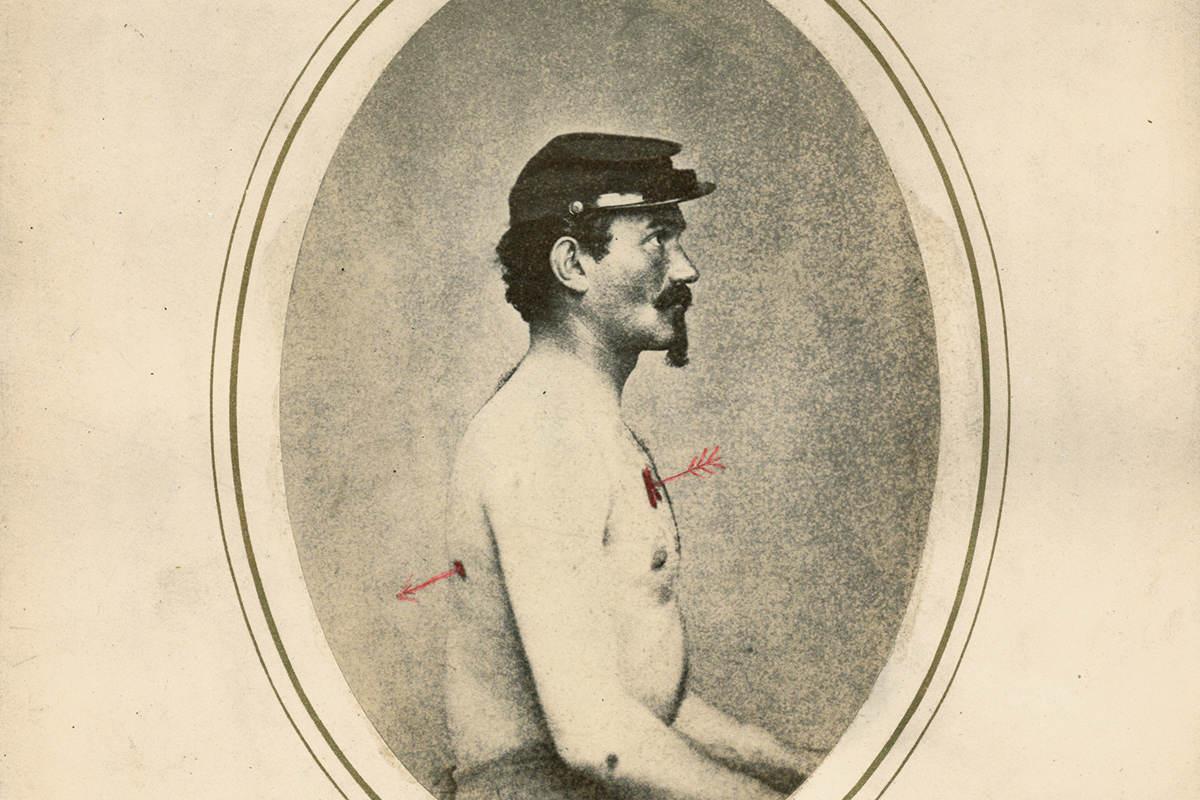

Harvard psychiatrist Steve Schlozman, who joined the symposium via Skype, is author of the book The Zombie Autopsies. “It’s clear when you see zombies, they are sick; there is something wrong with them. If they showed up in the ER, we would try to treat them,” said Scholzman, who came up with the term Ataxic Neurodegenerative Satiety Deficiency (ANSD) syndrome to describe the zombic condition.

“Clearly something is wrong with their frontal lobes, the executive function of the brain. The mechanism that lets them know when they’ve eaten enough, the ventromedial hypothalamus, is not functioning. And they’ve lost the ability to move with fluidity, which indicates the cerebellar and basal ganglia are out of the picture. Basically, they are NLH—no longer human—or as good as dead.”

Karen Rommelfanger, director of the neuroethics program at the Center for Ethics, got hooked on zombies after watching a scene in The Walking Dead where scientists were discussing whether the parts of the brain that give people their own identity and sense of self was wiped out by their zombification.

“These are exactly the kinds of questions we talk about in neuroethics,” Rommelfanger said. “Is the brain the seat of personhood? What does ‘brain dead’ really mean?”

Associate Professor of History W. Scott Poole of the College of Charleston, author of Monsters in America, discussed zombies as a symbol of sacrilege. “Zombies are nightmare versions of notions of Christian resurrection,” Poole said. “They are also the worst nightmare of a culture that is obsessed with exercise, dieting, and plastic surgery—bodies that are rotting away yet always eating. They are secular subversions; contemplation of the void.”

Alongside the fictional abstract, zombies have actually contributed significantly to the public’s disaster preparedness, according to two public health experts at the symposium: Rollins School of Public Health Dean James Curran and Martin Cetron, director of global migration and quarantine at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Are you ready for the zombie apocalypse? “Just Google CDC and zombies,” Cetron said.

What first began as a mock campaign to attract new audiences to public health and safety messages has proven to be a very effective platform. As Ali Khan 00MPH, director of the Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, notes on the agency’s website: “If you are generally well equipped to deal with a zombie apocalypse, you will be prepared for a hurricane, pandemic, earthquake, or terrorist attack.”

American zombies usually arise from a fear of science gone wrong, a contagion that invades our bodies and wipes out our individuality, said John Dunne, associate professor of religion at Emory.

But other cultures’ zombies are not always to be feared. Take Tibetan death meditation, in which practitioners can linger in their bodies after death for days or even weeks. His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama, a Presidential Distinguished Professor at Emory, has asked for scientific research to be conducted on this phenomenon, Dunne said.

“What are the ethical implications?” Dunne asked. “Perhaps we will discover that dying well is more important than life extension at all costs.”

Death, he said, reduces the mind to its simplest state—the “clear light of an August sky.”

“Just before the mind leaves the body to be reborn into another body of matter, the opportunity for spiritual progress is great,” Dunne said.

A good thing to remember the next time you hear the monotonous shuffle of a zombie behind you.