Objects of Our Affliction

Jeffrey Reznick safeguards the nation's collection of rare (and strange) medical memorabilia

Jeffrey Reznick 99PhD

Troy Pfister

Visiting the National Institutes of Health (NIH) headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland, ten miles north of downtown Washington, D. C., is a lot like walking across the grounds of an elite research university, albeit with upgraded security.

Red brick buildings open onto rolling lawns. Small groups of people wander by, intent on conversation—about the human genome project, one imagines. A brightly lit cafeteria serves strong black coffee.

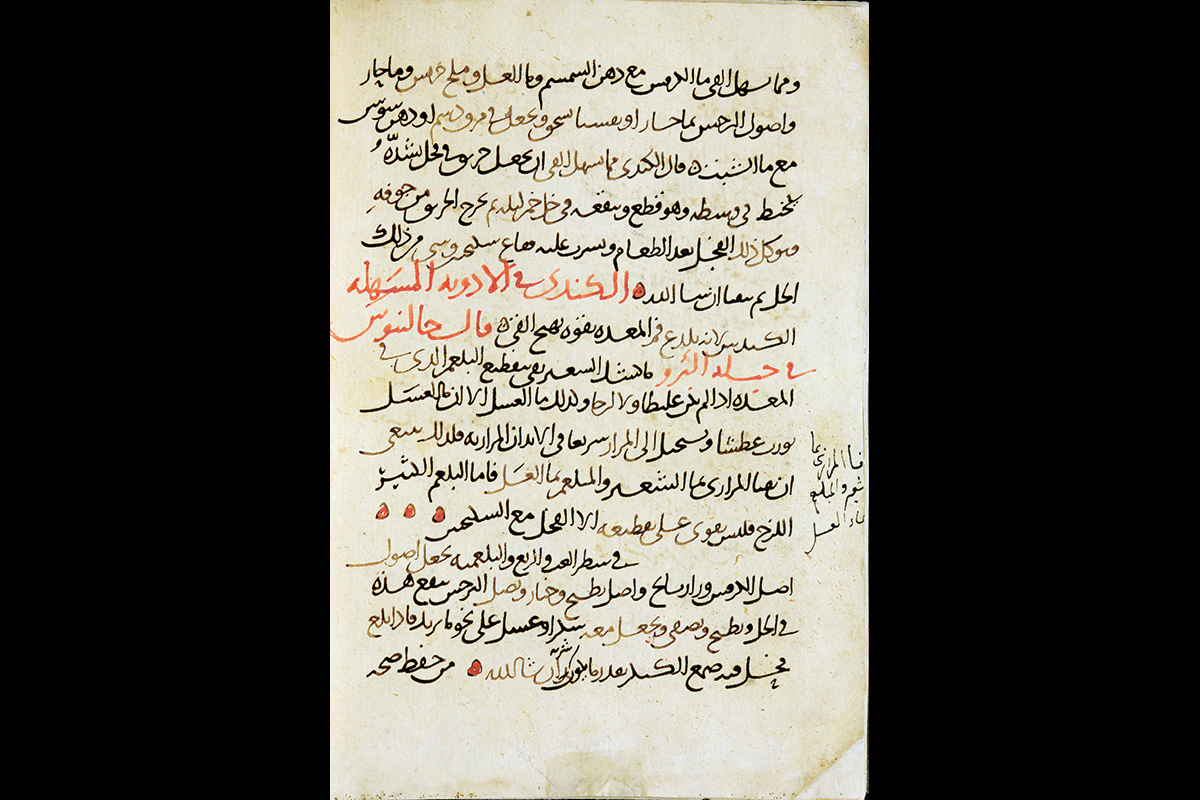

Although the campus is bursting with labs and research space, it is anchored by a massive library with a stately facade and a fascinating history. The US National Library of Medicine began in 1836 as a shelf of books in the Office of the Surgeon General and evolved to become the largest biomedical library in the world, concurrently housing millions of physical items and serving electronic data to millions of online users around the world.

“My fantasy holiday,” writer Mary Roach, author of the books Stiff, Spoof, and Bonk, has said, “is a week spent locked in the archives of the National Library of Medicine.”

Located in Ford’s Theater during the decades after Lincoln’s assassination, then occupying a spot on the National Mall, the library’s historic holdings were moved to Cleveland, Ohio, for a time during World War II to protect them from a potential attack by Hitler’s Third Reich. Moving to the NIH campus in the 1960s, the National Library of Medicine now stores its rare and valuable holdings in two intersecting worlds: analog and digital.

National Library of Medicine

Much of its paper collection is being digitized, with an increasing portion of its current acquisitions “born digital”—from online journals to researchers’ blogs. The library is perhaps best known for its free PubMed database, which contains more than 22 million citations and abstracts of articles from the fields of biomedicine and health, with half a million more added each year.

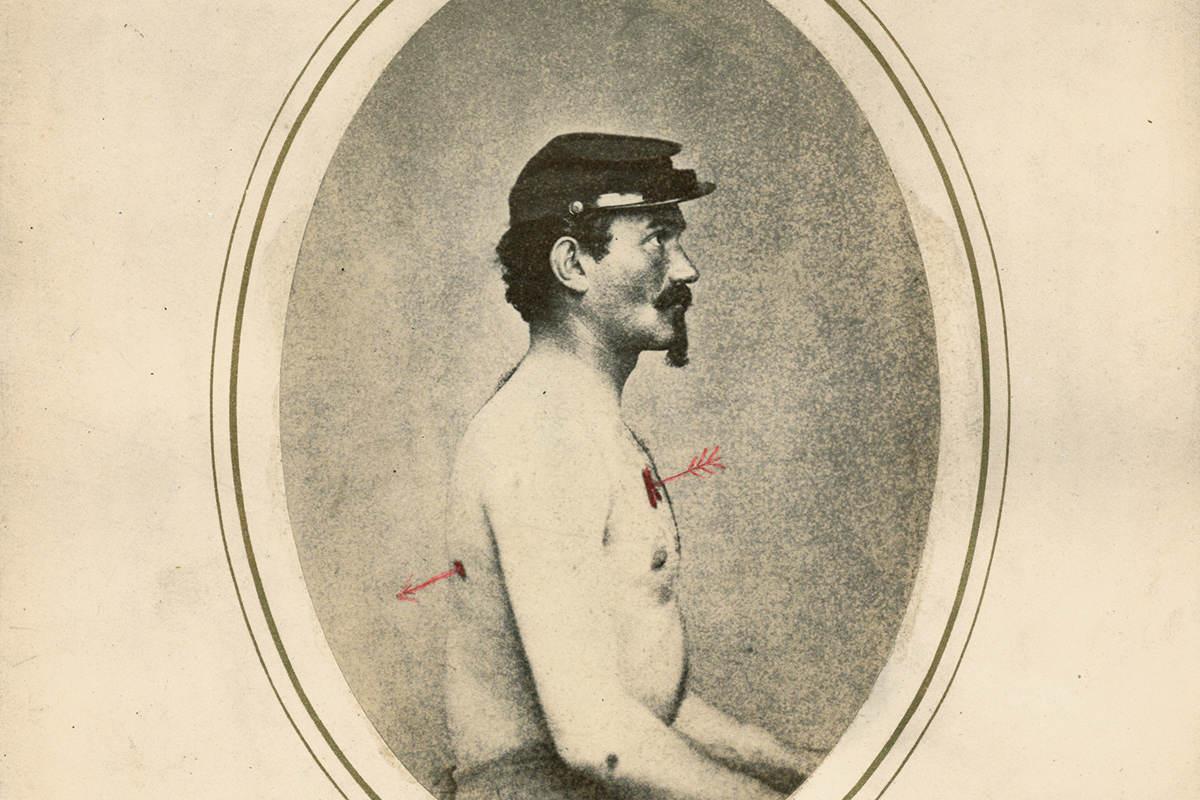

Today, however, promises a tour of the tangible—from palmistry guides to Civil War surgical cards to the first published illustration of Watson and Crick’s double helix.

Jeff Reznick 99PhD, chief of the library’s History of Medicine division, serves as a steward of some of the medical library’s rarest, oldest, and yes, quirkiest items. As a social and cultural historian of medicine and war and the author of two books, John Galsworthy and Disabled Soldiers of the Great War (2009) and Healing the Nation: Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain during the Great War (2005), Reznick is right at home.

“Welcome to the most beautiful building on campus,” announces Reznick, as he enters the spacious lobby of the library and heads to his book-lined office. “We’re not a lending library in the traditional sense, but a contemporary research institution that is home to an amazing historical collection as well as an extensive exhibition program.”

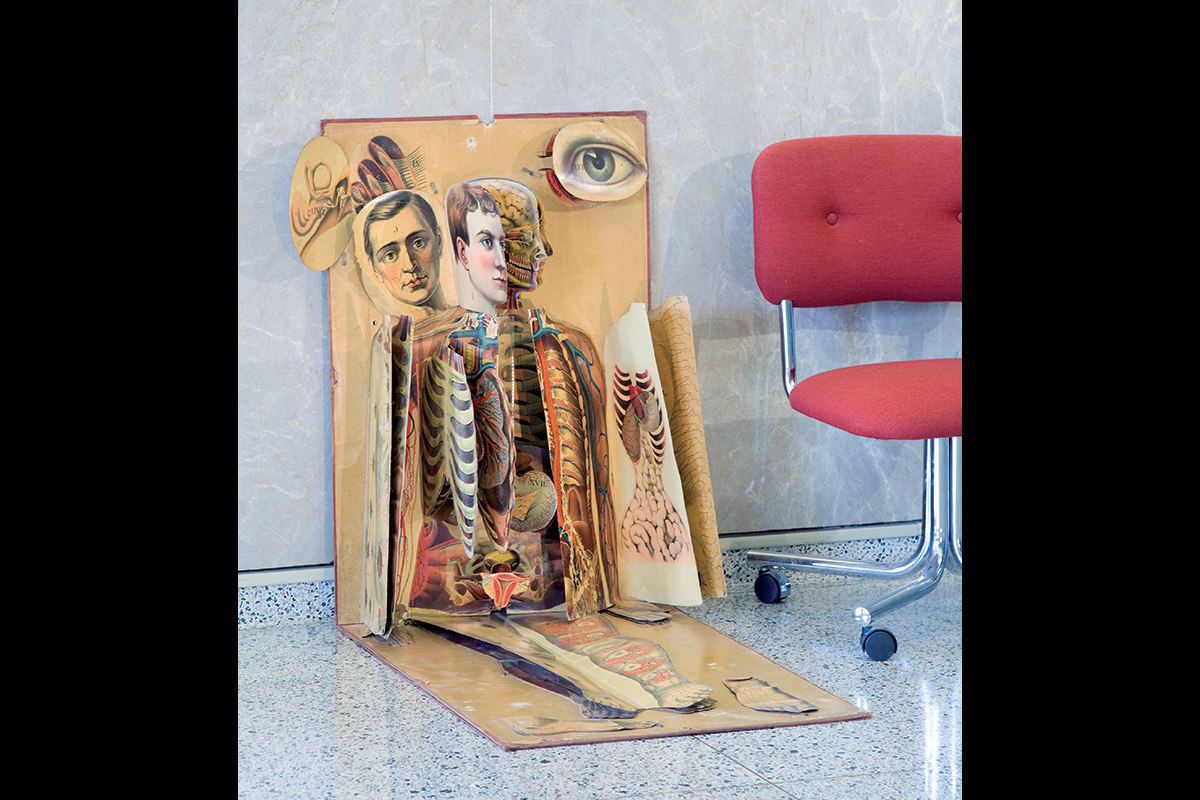

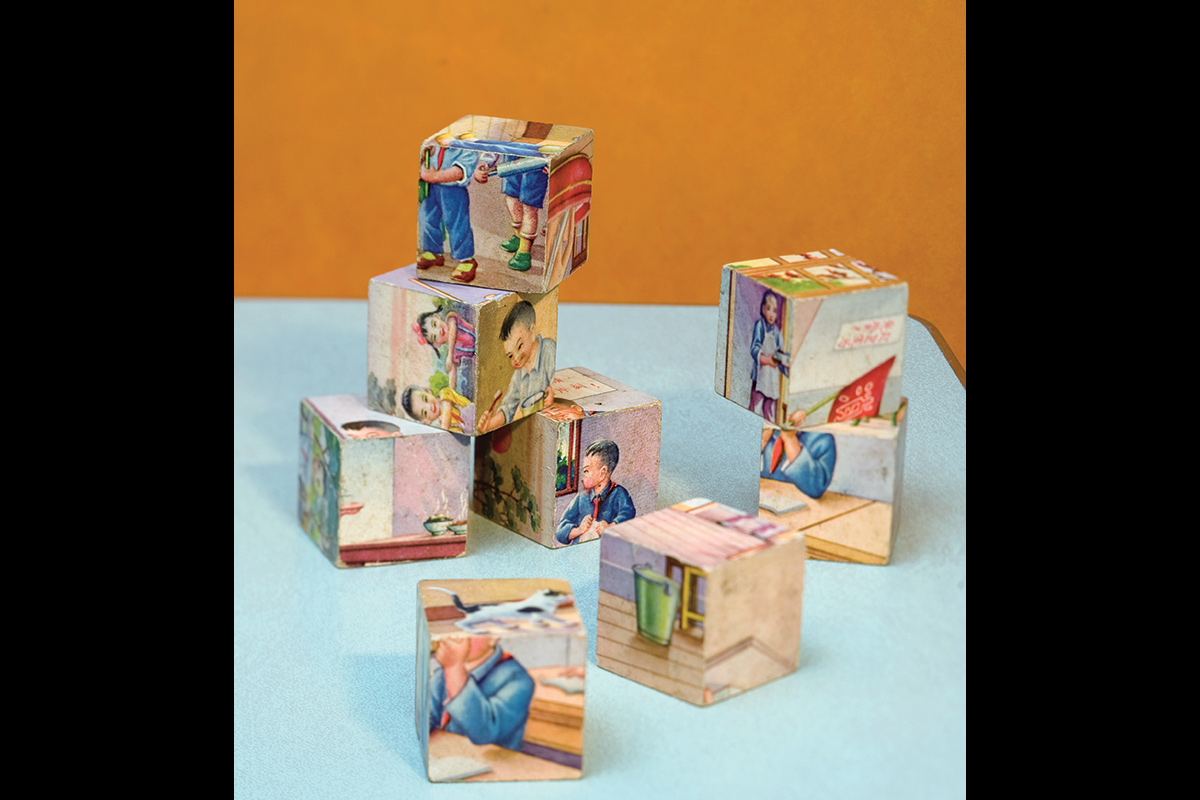

The collections contain medieval manuscripts, rare first editions, silent films, paintings, photographs, postcards, lantern slides, original drawings, hospital records, and laboratory notebooks—seventeen million artifacts that range from the famous to the obscure, the sublime to the repulsive.

Holdings date in era from ancient medical manuscripts to the proceedings of the latest AIDS conference, and the staff is constantly thinking about what will become historically significant in the future, which Reznick calls “prospective collecting.”

“We are always looking forward, even though people tend to think of libraries as retrospective,” says Reznick. “We are fortunate to have a modest budget that allows us to purchase rare and out-of-print materials. We also occasionally receive generous donations from individuals and other institutions, especially libraries that are downsizing and rethinking their collections and their physical spaces in the digital age.”

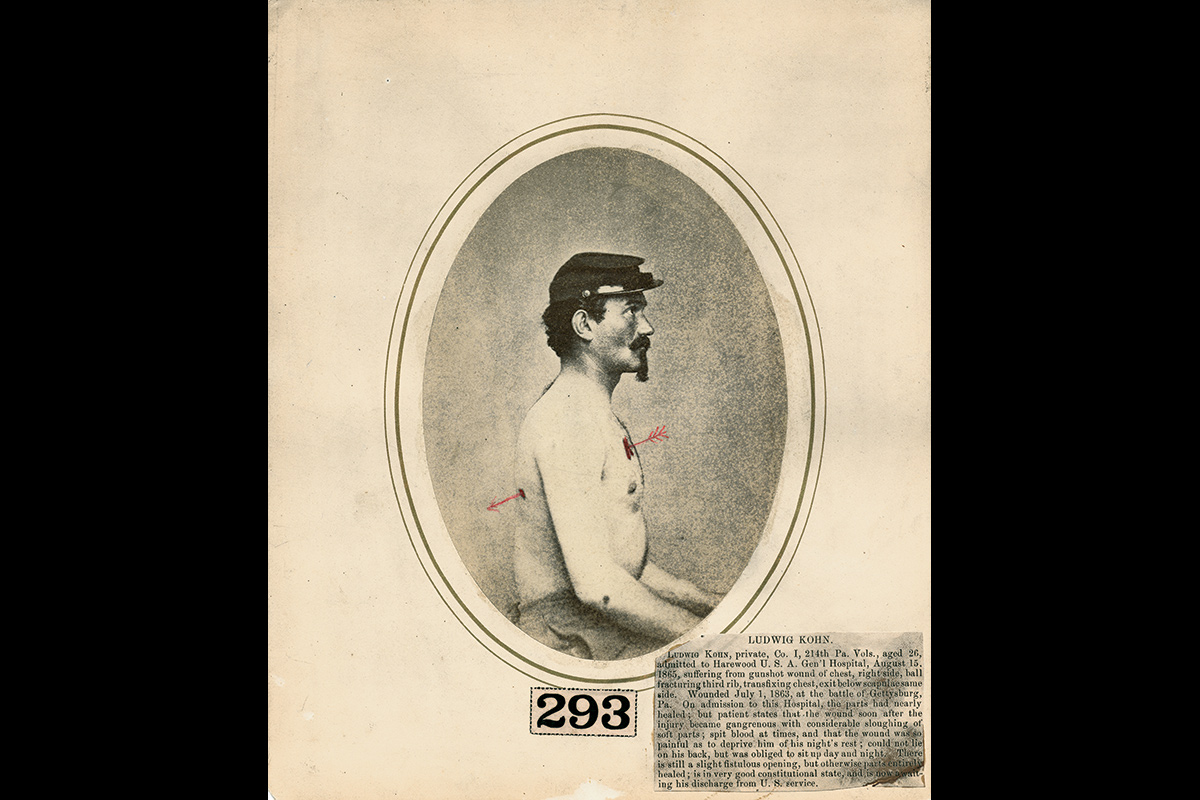

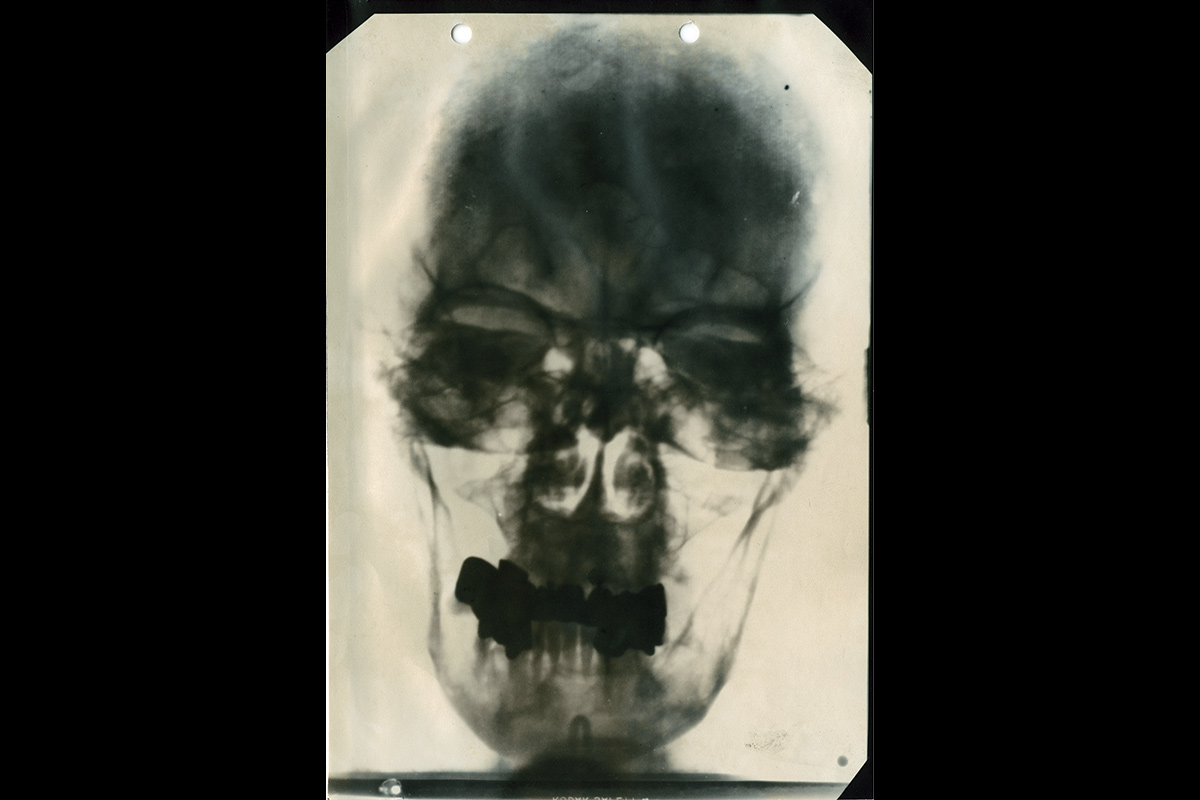

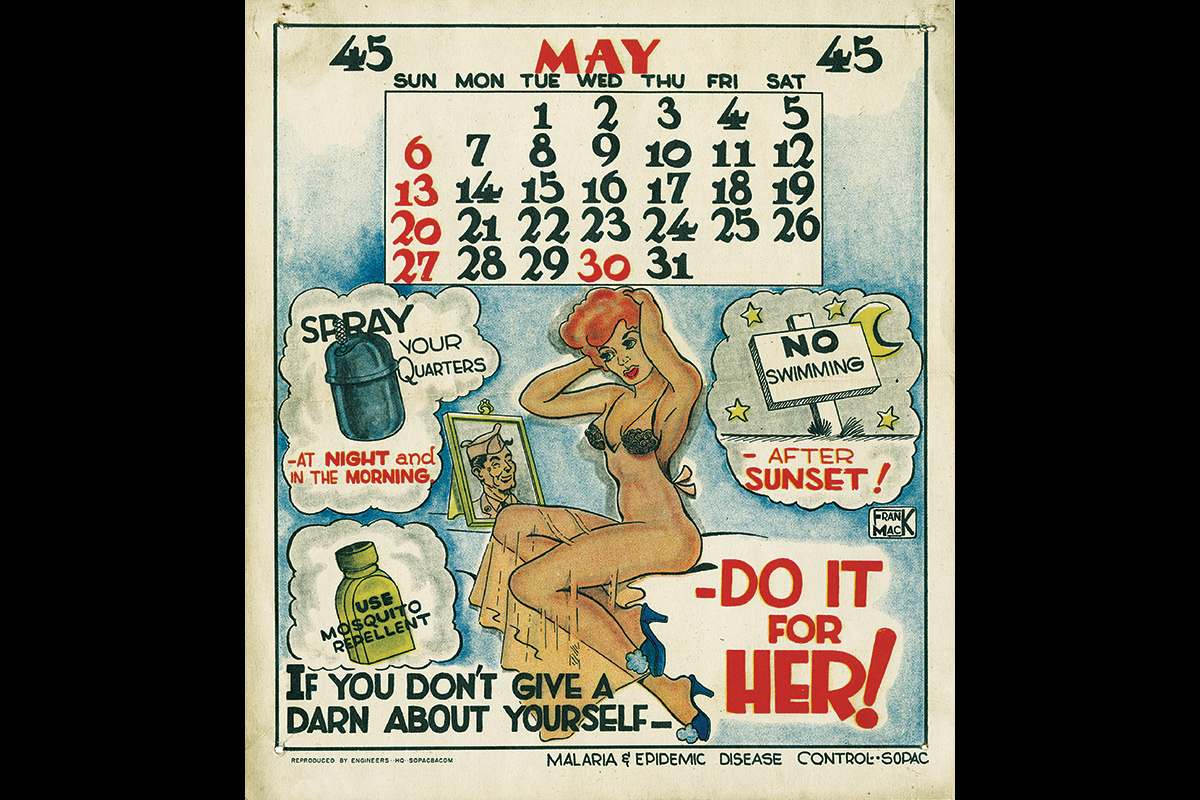

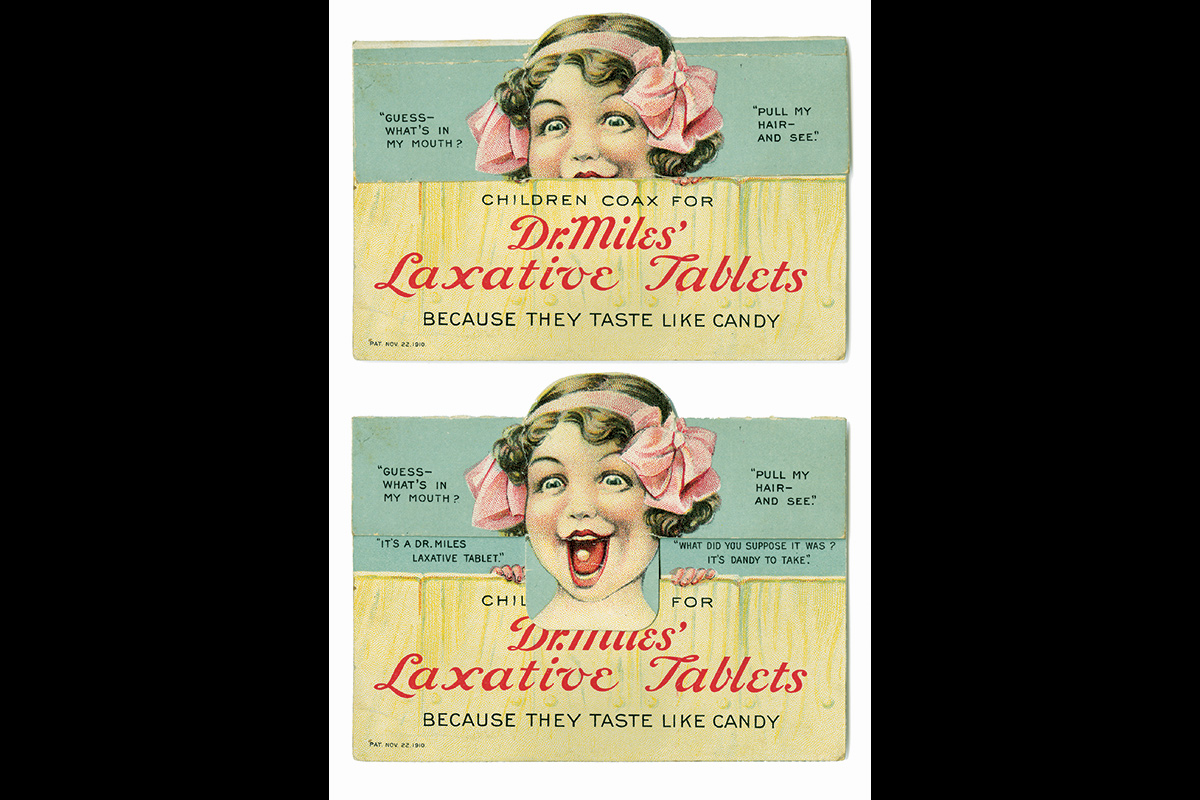

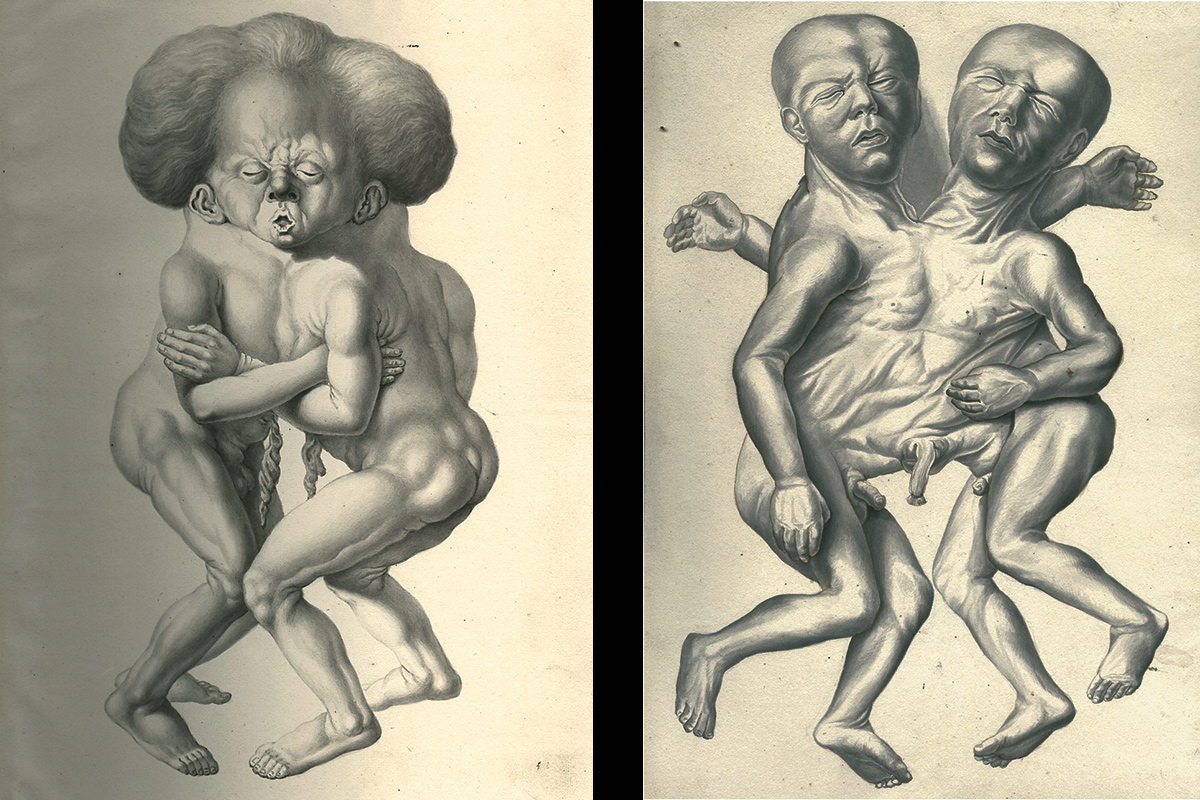

A selection of the library’s most captivating artifacts is highlighted in the newly published Hidden Treasure, edited by Reznick’s colleague and library historian Michael Sappol. The coffee-table book is filled with 450 vivid illustrations and essays. Within its pages are sketches of conjoined twins, Hitler’s x-rays, autopsy illustrations, midwife dolls, Darwin’s sketches, a grand atlas of skin diseases, public health warning cards, and malaria pinup calendars. Hidden Treasure (Blast Books, 2012) is available free as a downloadable e-copy, or as a hardbound book.

A review in The Lancet reads, “Each selection is truly intriguing and informative, reminding us that medicine is inherently connected to the human experience and all of its attendant complexities. As the images show, there are few, if any, areas of life that medicine does not affect.”

The book’s introduction, cowritten by Reznick, notes that “the occasion of the library’s 175th anniversary has provided us with an excuse to troll the collection, . . . which ranges in time from the eleventh century to the present and comes from nearly every region of the globe.

“These are things that are not entirely reducible to ‘information,’ that are only partly susceptible to digitization. They have a feel and texture and smell and color; they are strong or brittle, clean or dusty; they have been taken from place to place, bought or sold or bartered or stolen or issued or given away as gifts. They have been treasured or neglected, defaced or mended, added to or pruned back. Each object has lived a ‘social life,’ sometimes several lives.”

Emory Professor of English Benjamin Reiss, author of Theaters of Madness: Insane Asylums and Nineteenth-Century American Culture, says the library contains “an extraordinary collection and is underused as a scholarly resource.”

Reiss was invited to contribute an essay for Hidden Treasure on a set of magic lantern slides that were exhibited to mental patients in a nineteenth-century insane asylum. “The assignment led me on a really interesting historical detective mission, trying to figure out who made the slides, what the exhibits were like, and what role the exhibits played in the treatment of patients,” he says.

He found that many of the slides were part of patients’ “moral treatment,” meant to impress rational, orderly imagery—such as snowflakes—upon their minds, while others, such as a giant flea attacking a man in a chair, were for entertainment. “Given that many patients were delusional and/or medicated with dream-inducing opiates, one wonders about the wisdom of serving up these ready-made hallucinations, magnified to terrifying proportions,” Reiss writes.

Most of the items featured in the book—as well as thousands of other interesting, unusual, and irreplaceable curiosities—fall under the care of the History of Medicine Division, with its trained staff of historians, cataloguers, curators, librarians, and conservators.

The rarest and most fragile materials are kept in the Incunabula Room near Reznick’s office. It is that climate-controlled room—a bit chilly, smelling faintly of ancient parchment and old newspaper clippings—to which Reznick, and we, welcome you in our slideshow.