Book of Revelations

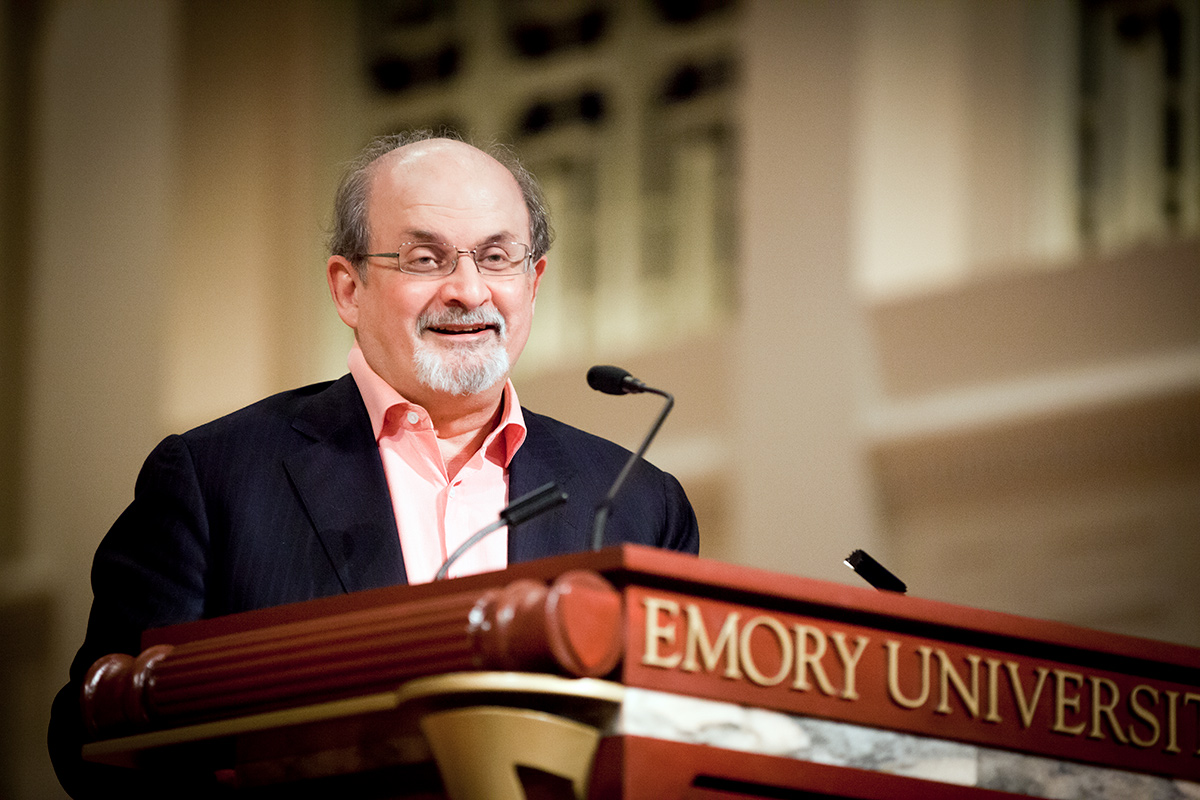

Salman Rushdie and `the curse of an interesting life'

Ann Borden

On a chill November evening in Glenn Memorial Auditorium, Salman Rushdie found himself reading from a book he once thought he would never write: his memoir.

“I was not interested at all; I find it to be the most tedious form. I became a writer to make things up, to write about people who were not me and things I hadn’t done,” he said. “Then I got the curse of an interesting life.”

On Valentine’s Day 1989, a fatwa was issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini in response to Rushdie’s fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, which the leader said was “against Islam, against the Prophet of Islam, and against the Koran.” Khomeini called on all “valiant Muslims” to carry out the sentence of capital punishment for the author and everyone associated with the book’s publication.

When Rushdie, now a University Distinguished Professor at Emory, fled his London home under British police protection, he thought it would be for a few days, hoping that the fatwa amounted to nothing more than “rhetorical fist-shaking.” It wound up being a decade before he could resume his normal life.

For the first time, he reveals details of those years spent in hiding—falling in and out of love, moving from house to house, worrying for his young son’s safety, getting remarried, and allowing his friends (including many of London’s literary elite) to protect him—in Joseph Anton: A Memoir, published in September 2012.

The title comes from the alias he used, which he came up with by combining the first names of favorite writers (in this case, Conrad and Chekhov). “Some of the combinations I tried were ludicrous . . . Vladimir Joyce,” he said. “But that’s how ridiculous that time was. I had to surrender both my name and my ethnicity.”

His experiences during the fatwa were sometimes terrifying, and sometimes funny, he said—including a visit to the United States in which he was expected to ride incognito in a stretch limo in the middle of a motorcade. Life in hiding “took on the double quality of satirizing itself,” he said, even as protestors in the streets called for his death. “In my mind, it became a battle between people who had a sense of humor and people who did not.”

In writing the memoir, aided greatly by the organization of his papers in Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Rushdie said he hoped to place his personal situation within the larger context of defending the freedom to write and speak one’s mind.

“I will hopefully never have to talk about the fatwa again,” said Rushdie. “I can just point to this book and say, there’s six hundred and thirty pages. Now leave me alone, it’s all in there.”