In Search of the Social

From eye-tracking technologies to the 'trust hormone,' earlier diagnoses and new interventions hold promise for children on the autism spectrum

Kay Hinton

The bright-eyed, five-month-old girl gazes at the screen, mesmerized by the moving white dots. The "point of light" display is meant to identify where her eye lingers and whether she shows a preference for "biological motion," such as a simulation of pat-a-cake.

Researchers at the Marcus Autism Center observe her reactions from a bank of monitors nearby: the first shows what the baby is watching, the second is a close-up of her eyes, and the third captures her facial expressions.

We humans are social creatures. From the time we are born, we orient toward other people, watching their expressions and gestures. An infant just a few weeks old will stare at her mother's face, look long into eyes, and mimic facial expressions. This selective focus leads to "mind reading," an ability to tell what others—even strangers—are thinking, feeling, or intending to do, often from just a glance. It's a tendency we have from birth, and a skill we continue to develop for life.

It's different, though, in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

They start off at a disadvantage and compound it by continuing to pay attention to the "wrong" things—hats instead of hands, shoes instead of faces. Autistic children watching cartoon shows, such as Barney, are as likely to focus on a light switch on the wall as the singing, dancing purple dinosaur.

This lack of interest in human action, believes Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar and Emory Professor of Pediatrics Ami Klin, who has conducted landmark research studies in the field, is key to understanding why autistic children never master the complex nuances of social interaction.

"The lack of preferential attention toward biological motion is consistent with diminished attention to the eyes and diminished expertise in social action and interaction found in later life," Klin and his fellow researchers concluded in a 2009 study published in Nature.

So how do we teach these children what most of us were born knowing? How do we enhance their social brain? That is, literally, the hundred-million-dollar question.

Originally from Brazil and educated in Israel and England, Klin is director of the Marcus Autism Center, and director of the Division of Autism and Related Developmental Disabilities in Emory's Department of Pediatrics. He came to Atlanta in January 2011 after being courted by philanthropist and Home Depot cofounder Bernie Marcus—who, the story goes, told Klin he would be a "schmuck" not to make the move, even though it meant leaving a titled professorship and tenured position at Yale University in autism research.

Ami Klin

Children's Healthcare of Atlanta

"Very much a true story," Klin says. "We spent four hours in his office going over an eleven-page document I had written, a kind of vision statement. He had read it and colored it all in yellow. I wasn't looking for a new job, I'd been twenty years at Yale. But he convinced me that here in Atlanta, there were all the makings for an opportunity that would not be replicated anywhere else, any time soon."

Klin pauses.

"Bernie and I have very similar attitudes to life," he said. "We like to make things happen, and to happen on a grand scale."

Not only did Klin and his family move from New Haven to Atlanta, he convinced his eighteen-person research team and their families to move as well, and he is continuing to recruit top autism researchers and clinicians from around the country—"people with energy and enthusiasm, transformational people who have bought into the mission and the vision."

Autism, he says, can keep a family in a "state of siege. Our mission isn't to write another beautiful research paper, it's having the privilege of putting these families and children first, of addressing something that impacts one in eighty-eight children, of changing the landscape of the field. We don't want to go back to the time when having a child with autism was a private matter. This is a public matter."

It's an expensive public matter. Treating a child with autism costs about $80,000 a year, and Klin estimates that autism costs the United States about $140 billion annually.

Autism is now more common than childhood diabetes, or all childhood cancers put together. Early intervention could greatly reduce the cost of what is fast becoming a public health crisis.

The earlier autistic children can be helped to focus on social cues, Klin says, the less costly it is to educate and provide therapy for them. The first responders in this case are parents and pediatricians.

Eye Contact: The Marcus Center is testing babies whose older siblings have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder to see if they watch eyes and faces and favor "biological motion" as typical infants do.

Kay Hinton

"We have discovered that markers of risk for autism can be identified early in infancy, although actual behavioral symptoms don't emerge until the second year of life," Klin says. "The brain depends on human experiences in early development, so if we can capitalize on that initial window when the brain is still able to adapt and change, we believe we can raise the prospects of significantly altering the natural course of ASD."

In September 2012, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that it would grant awards of $100 million over five years for autism research at premier centers across the country, as well as to networks of researchers from different institutions working on the same question. Selected for support were three Autism Centers of Excellence (ACE)—consortiums of centralized research—in Los Angeles, Boston, and Atlanta.

"Our state has now become a national leader in autism research and treatment," said Georgia Governor Nathan Deal.

The center at the University of California will use imaging to chart the brain development of individuals with genes suspected of contributing to ASD, and devise treatments to improve social behavior and attention in infants and the acquisition of language in older children. The center at Boston University will use brain imaging to understand why individuals with autism do not learn to speak as readily and what can be done to help them overcome that limitation.

The center in Atlanta, which received an $8.3 million award, is led by Klin and based at Emory and the Marcus Autism Center (part of Children's Healthcare of Atlanta). Partners include the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Georgia Tech, the Rollins School of Public Health, and the NIH-sponsored Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

The Emory team will investigate risk and resilience in ASD, such as identifying factors associated with positive outcomes or social disability. Marcus Center researchers will study social visual engagement and social vocal engagement, starting in one-month-old infants. They plan to begin treatment in twelve-month-olds in randomized clinical trials. And, through parallel studies in model animal systems, researchers will chart brain development of neural networks involved in social interaction. The overriding goal is to better understand how autism and related disorders unfold across early development.

As high as autism rates are in the US, they are even higher in Georgia, says Marcus, who founded the Marcus Autism Center in 1991. "One in eighty-four children is affected here," he says. "This boost to the research engine at Marcus Autism Center is going to have an enormous impact on thousands of lives. It will transform the way we identify and care for children with autism, allowing us to better serve them and their families."

In addition to being a hub for integrated research, the Marcus Autism Center provides diagnosis, family education, behavioral therapy, and support services, seeing eight times more children with autism than any other center in the US—more than 5,600 in 2011 alone.

For many families, it is, as Thomas Dunn's mother calls it, "our launching-off point."

Thomas is a bright, engaging twelve-year-old from Marietta who loves video games, Pokemon, and anything about President Abraham Lincoln. He is living proof that early intervention works. As Thomas tries to identify the fish in the Marcus Center's oversized aquarium ("Hey, mom, are those bottom feeders?"), his mother, Terri Dunn, talks about the fear of not knowing what to do for her son when he was small.

"My mom pointed out to me when Thomas was two-and-a-half that he was slow, but I didn't know anything about autism. Back then it wasn't as well known as it is now," she says. "I took him to his pediatrician, who got him into the Babies Can't Wait program, and he went to a pre-K when he was three that was inside his elementary school. When he went there, he couldn't even sit up on his own. By the time he left preschool, he was talking, walking, and reading."

Terri moved in with her own mother so she could stay at home to give Thomas the support he needed. "I'd try working, and he'd start slipping," she says. The Marcus Center supported her, working with Thomas's schools to create action plans. The sixth-grader has coteachers in the classroom, extra time to get to class, and special organizational tools to "level the playing field," says his mom. He exceeded expectations on all areas of his CRCTs except math, in which he met expectations, said Terri, and he is reading at a ninth-grade level.

"Believe it or not, Thomas has severe autism, but is highly functioning," she says. "Without the help and resources available here at Marcus, I don't think a lot of parents would know what to do or where to go. He has progressed so much. Now he's hitting a plateau, so we've come back again to check in and see what we can do."

This is the first year, for instance, that Thomas has taken medication—Celexa (citalopram)—for his disorder. "He would have anxiety at his school about going into a crowded room for the first time, and his anxiety was getting the better of him and he was getting angry," she says. "This helps him calm himself. There haven't been any more outbursts."

The center functions as a safety net for the state, with 70 percent of the children seen there on Medicaid. "It is vital to get these children and families involved in research," Klin says. "These are low-income children, minorities, the rural population, people who usually fall outside the realm of the best medical care. Here we have the opportunity to extend the reach of our science."

Autism is a genetic disorder at root and nearly five times more prevalent in boys. "It is a genetic liability that may or may not convert into clinical reality," Klin says. "Diagnosis is based on behavior that is observed. But it is also a brain disorder, in that genetics impact the brain."

William P. Timmie Professor of Psychiatry Larry Young, author of The Chemistry between Us (2012), arrived at autism through his research on mammals and monogamy.

As founder of Emory's Center for Translational Social Neuroscience, which includes neurologists, geneticists, psychologists, primatologists, and other specialists, he believes a multidisciplinary approach is vital to treating disorders of the social brain.

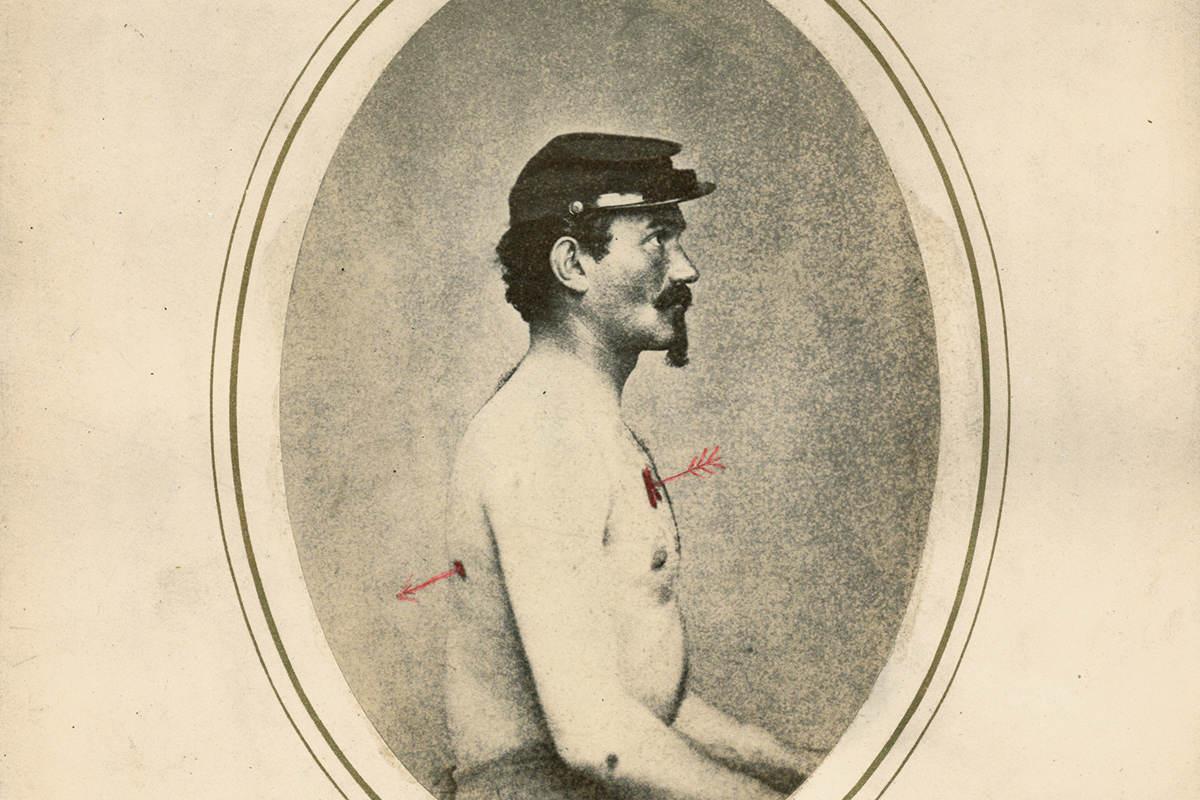

Bonding Time: Children's Healthcare of Atlanta speech-language pathologist Natalie Brane plays with her five-month-old daughter, Ansley, who is taking part in a Marcus Autism Center study on eye tracking.

Kay Hinton

Young's office at Yerkes sits a few floors above a vivarium filled with prairie voles, small mammals researchers use to study pair bonding and maternal bonding. "Our brain is naturally a social brain," Young says. "We look into each others' eyes. Why not the mouth, or the nose? Because the eyes increase our ability to infer the emotions of others."

This attunement is part of an ancient, evolutionary drive that begins with maternal behavior, Young says, but extends more subtly into our everyday interactions.

When Young was working with prairie voles, trying to decipher the chemicals that formed attachments between mates and that influenced monogamy, he found the hormone oxytocin (not to be confused with the synthetic opiate oxycontin) was essential in forming bonds between the vole pairs. Now sometimes called the "trust chemical" or the "love chemical," oxytocin was found to be released in large amounts after childbirth, during breastfeeding, lovemaking, and even with a simple touch like a hug.

"So here's a hormone that increases trust, gazing into eyes, inferring emotion, the ability to remember faces, and empathy—all things that are challenging to someone with autism," says Young. "It helps to develop pro-social behavior."

He envisions oxytocin not as a daily medicine to be given to people on the autism spectrum, but as a potential catalyst to boost therapy's effectiveness. Investigators working with autism and intranasal oxytocin (administered in a nose spray) have found that the subjects do spend more time looking into eyes and are better at reading other people's emotions. "Oxytocin facilitates social learning," Young says. "It's very short-lived; the effect lasts for only a few hours, but given strategically, it could really enhance social learning."

Diminishing symptoms and augmenting skills are at the core of autism research and treatment, says Klin, who believes the future lies in universal screenings, early detection through pediatricians' offices, and giving parents, not just professionals, training and therapeutic tools.

"To diagnose a child without having anything to offer the family would be unethical," he says. "When I go to work in the morning, that is what drives me. What can we do in order not to disappoint these families who have placed their trust in us?"

Seventeen-year-old Jennifer Simmons was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome when she was in fifth grade, and has received therapy at the Marcus Center, but she has come to see the disorder as a "blessing instead of a curse."

"There hasn't been a great achiever throughout history who hasn't been a bit strange or peculiar," Jennifer says, pointing to Einstein, Bill Gates, and Satoshi Tajiri, the inventor of Pokemon. Jen enjoys Pokemon herself, which fits with her love of taxonomy. She has also created an imaginary land, Tokkia, with a queen, parliament, and history that rivals a Tolkien fantasy world; she watches the BBC for her news, and speaks with a British accent much of the time.

Her favorite animal is a carnivorous sea sponge which, "just like me, was recently discovered, and has great potential for redefining what being a sponge is all about. I see myself as that strange sea invertebrate, unique among my crowd and destined to come up with some kind of breakthrough."

"Jen is an incredible person," says her mother, Mary Simmons, director of gift planning in the Office of Development and Alumni Relations at Emory. "She is very smart and talented, writes poetry, and loves science and politics. But the flip side is that she has the interests of an eight-year-old boy—Pokemon and video games. Like many on the spectrum, everything is either black or white, she doesn't see gray, and most social rules and niceties don't make sense to her."

Jen attended public school until seventh grade, when things like changing classes or entering a crowded, noisy lunchroom became overwhelming; she now attends a small, private school and takes courses online.

"Sometimes my thoughts are like a beehive, I can't catch just one," she admits. "I get knackered by seven p.m. most nights, but my mind won't shut up until midnight, and goes on into my sleep. I dream lucidly, always."

She maintains a wicked sense of humor about her diagnosis, and has a host of sayings that begin, "You might be an Aspie if…" that she recounts with a smile: "You might be an Aspie if you don't walk, you bound." She's also created a comedic skit called Aspie Spy Ninjas, who yell out the content of secret messages and always announce their arrival.

But it's not always easy to make light. "I know that I will never be a typical teenage girl, anymore than I could be a pink pig," she says. "I would be living a lie."

Research at Emory's Autism Center of Excellence (ACE)

Marcus Autism Center Director for Research Warren Jones, Spoken Communications Lab Director Gordon Ramsay, and Director Ami Klin will continue pioneering eye-tracking, social engagement, and speech science studies in infants as young as one month, searching to uncover factors that are predictive of ASD as early as possible. Researchers will use "growth charts" that compare normal social engagement and deviations in the first year of life.

Collaborator Amy Wetherby, distinguished research professor and L. L. Schendel Professor of Communication Disorders at Florida State University, will focus on early treatment that can change the developmental trajectory of autism. Wetherby has been a leading investigator of effective early screening and treatment for toddlers with ASD. She will use proven procedures with social communication to screen infants before their first birthday and carry out a randomized clinical trial for treatment beginning at twelve months.

The Yerkes National Primate Research Center will study rhesus macaques, connecting eye-tracking behavioral studies of visual engagement and "growth charts" of social engagement with genetics, behavioral, and brain imaging studies in nonhuman primates. Professor of Psychology Jocelyne Bachevalier, who described the first nonhuman primate model of autism, leads the project with Assistant Research Professor Lisa Parr 00PhD and Associate Professor Mar Sanchez.