Coda

The Last Letter

“For the past three months I’ve been carrying your letter and the fall 2009 Wagner alumni magazine around with me in my briefcase,” Max Aue began, in his bold, old-fashioned Austrian cursive. “Each time I bump into them, I am touched and delighted again.”

His letter was dated April 10, 2010. It sat on my desk for three years; his letter didn’t necessarily call for a response, but I always meant to keep the correspondence going. But then, on March 17, in a conversation with another Emory professor, I learned that Max had died last August, in a traffic accident.

Max Aue was a teacher with a very special gift. I thought about him and his way of teaching when I was reading and writing about a book called Learning as a Way of Leading: Lessons from the Struggle for Social Justice, by Stephen Preskill and Stephen D. Brookfield. Preskill is on the faculty of Wagner College, and I was reviewing the book for the alumni magazine.

My article, “What Does It Take to Be a Leader?” (published in the fall 2009 issue of Wagner Magazine), began this way:

One of my favorite professors in graduate school was Maximilian Aue. . . . His literature seminars always produced gem after gem of insights that made me look forward to every class meeting.

How did he do this? . . . He simply sat with his students around a table and focused on our questions. He began every class by asking, “Where were you confused?” Starting there, he insisted, would always lead us to the heart of the matter, and he was right. . . . When you begin a class by admitting to something you did not understand, it gives the conversation a remarkable openness. Each class felt like a voyage of discovery.

My point was that, in his teaching, Max Aue exemplified leadership qualities that Brookfield and Preskill saw in leaders of social justice movements: Leadership that is self-effacing, focused on others, collective. It’s the kind of moral leadership that, Preskill told me, “is found in more democratic-type classrooms, where we’re inviting a lot of student participation, where the learning is not so much centered in the teacher but in everyone’s conversation together.”

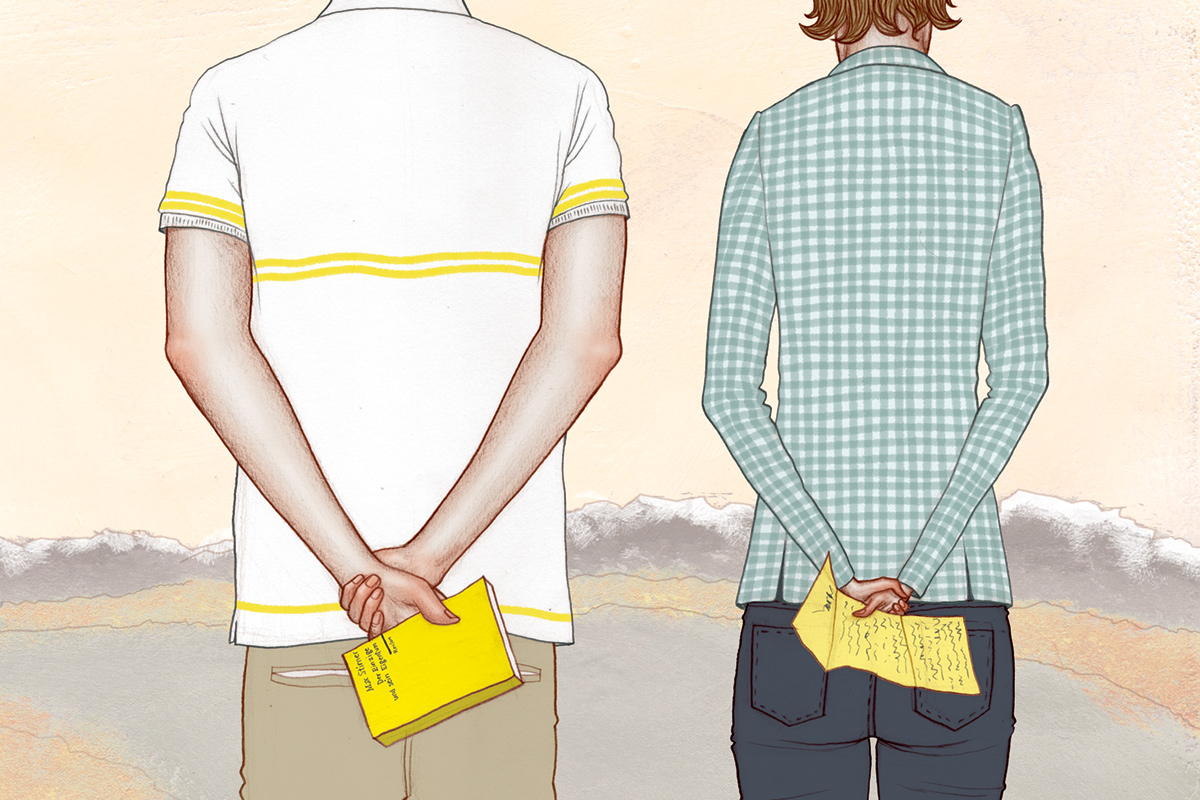

I took several seminars in German literature from Max, and he was on my dissertation committee as well. He always dressed informally, in khakis and polo shirts that were a bit faded and tattered with age. He biked to work, his right pant leg in a metal clip so it wouldn’t get caught in the chain. I picture him in those small seminar rooms in Trimble Hall, with a handful of students around the table, discussing Storm, Keller, Musil, Rilke, Fontane, Mann—all the masters of the great, late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I picture his craggy, lean face, his brow furrowed with concentration, his hands clutching one of those tiny yellow Reclam paperbacks (if you’ve ever taken a German lit class, you know what I’m talking about). I hear his Austrian-inflected German, as he patiently asked us question after probing question. As he guided the conversation, he took nothing about these texts for granted; he made it feel as if he were discovering the text for the first time, just as I was. And somehow, without telling us anything, he led us to insights that always amazed me and made me fall in love with those texts.

Back to his letter: “Each time I bump into them I am touched and delighted again—delighted that you still remember those courses and touched that you took the time and the trouble to let me know that they meant something to you.”

Yes, they meant a lot to me, and Max’s way of respectful yet challenging student-centered teaching, of leading us on those voyages of literary discovery, is no doubt what made them so meaningful and memorable. I’m so glad I did let him know, even though I never thought it would be my last contact with him; he was only sixty-nine when he died.

“In my experience, university teachers just don’t get this kind of response very frequently,” he continued. “I feel very fortunate and energized by your kind words.”

Ever the dedicated adviser, he went on for a couple more long paragraphs encouraging me in my work at Wagner College (which includes Fulbright advising) and life here in New York (especially my efforts to keep up my German). And, since I had dared to write my letter to him in German, it was a thrill that he praised my use of German in his own elegant style.

Max Aue was a great man who exercised a rare form of moral leadership that is seldom recognized: One that puts self aside in favor of uplifting others. For that, he earned my highest respect and love.

Laura Barlament 01PhD is associate director of communications and marketing at Wagner College in Staten Island, New York.

Email the Editor