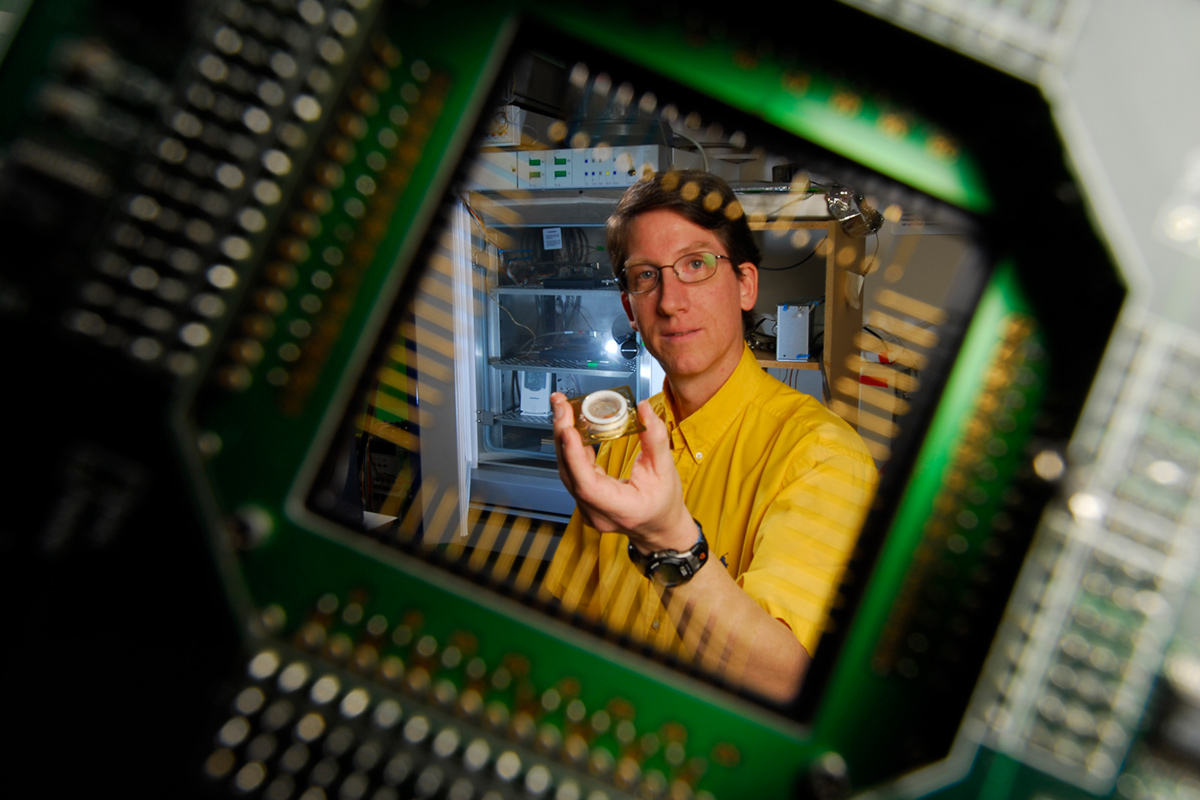

Portrait of the Artist

Alum artist Brendan O'Connell captures impressions of Walmart

Essdras M Suarez/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

When Brendan O'Connell 90C graduated from Emory with a degree in philosophy and Spanish literature, he thought he'd go on to become a writer. He didn't anticipate becoming a visual artist instead—certainly not one who would become known for his paintings of Walmart. He didn't plan to learn how to draw while living in Paris, making a modest living doing "pay what you wish" caricatures for tourists. Nor did O'Connell expect he would happen to meet actor Alec Baldwin during his six-year stint living abroad in Europe's cities. He didn't foresee that Baldwin would become an important collector and champion of his work, and he probably didn't expect that the two men—who bear an uncanny, brotherly resemblance to one another—would forge a friendship that endures to this day.

But such is the life of the artist: so much depends upon the convergence of being in the right place, at the right time, with the right people. O'Connell has learned a lot about that this year.

There are other things O'Connell didn't expect, like the consequences of being the subject of a five-page profile in the New Yorker this past February. "I knew [the article] would be a calling card, but I had no idea it would be quite this big," he says. O'Connell had received press before, including a write-up in Art in America, but nothing of the scale or scope of the New Yorker profile, which introduced the artist and his Walmart paintings to a new audience.

The well-known author of the profile, Susan Orlean, says she knew O'Connell before she wrote the article for the New Yorker; their children went to school together and she considered O'Connell "a good friend." While Orlean normally doesn't write about people she knows, she made an exception for O'Connell because she considered his work particularly compelling. She believed that what she describes as O'Connell's "interest in dignifying ordinary experience and being artful in interpreting an environment we never think of in those terms" would be as fascinating to the magazine's readers as it was to her.

O'Connell hadn't even had a chance to read Orlean's article ("I don't have a subscription," he confesses) before he received a call from The Colbert Report, whose producers booked him for a five-minute, forty-four-second segment that aired in March. "Do you know that only two other artists have been on Colbert?" he asks. "Jeff Koons, who's like the richest living artist, and Shepard Fairey, who has something like one hundred thousand followers on Twitter." (Actually, Koons occupies the second richest artist spot, behind Damien Hirst, and Fairey has 133,024 followers, but who's counting?)

Orange Coat, 2010, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy Brendan O'Connell

He pauses, as if taking it all in: Koons and Fairey are major leaguers. To be in their company, if only by Colbert's association, O'Connell must be, too.

In the segment, host Stephen Colbert compares O'Connell's painting of Jif peanut butter jars lined up on a Walmart shelf to Andy Warhol's soup cans (a comparison O'Connell has now heard dozens of times). He says he'll start shopping at Walmart more often if the store's shoppers are as attractive as the model who appears in one of O'Connell's paintings ("That's my wife," O'Connell says, eliciting guffaws from the audience). Colbert attempts to explicate O'Connell's pedestrian paintings of America's most loved and most hated retailer, asking O'Connell afterward, "Does what I just said mean anything?" (More laughter.) And though he pokes fun at O'Connell for selling his most expensive work at a price point the average Walmart shopper can't possibly afford, Colbert ends the segment by suggesting that O'Connell should look forward to selling many more paintings, thanks to the "Colbert bump," a neologism Colbert coined to refer to the sudden increase in popularity of someone who has appeared on his show. His tone changes from comic sarcasm to genuine admiration. "I love these," Colbert concludes about O'Connell's paintings, as the studio audience claps and hoots enthusiastically.

A month later, O'Connell was featured on NPR's popular food blog, The Salt, and in July, he hit the front page of the Boston Globe, noting, with some glee, that the story about him was considerably larger than the announcement of the royal baby's birth. "Front page," he says again, as if he's tickled and still can't quite believe it. "It must have been a slow news day."

So far, 2013 has been a record year for O'Connell, who lives in rural Connecticut with his wife, Emily Buchanan—also an accomplished painter—and their two children. The couple makes a conscious effort to live simply and nurture their creativity as well as their young family.

Bras, 2013, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy Brendan O'Connell

Having worked in the relative obscurity that characterizes most artists' careers since returning to the United States from Europe in 1997, O'Connell finds the sudden interest in his art highly gratifying and perhaps a bit overwhelming, too. The media attention has resulted in a bump in sales of his work, as Colbert predicted. That's nice, O'Connell concedes; "I like not stressing over a phone bill." And he's grateful to Susan Orlean, the New Yorker writer whose profile of him precipitated the mass interest in his work.

But the attention has complicated things, too. "I kind of thought all this would happen twenty years ago," he says. "You know, you have these delusions of grandeur when you're young and setting out. By the time [success] actually happens, your life is already set in its own patterns."

O'Connell doesn't reference Warhol's quote about fifteen minutes of fame directly, but he knows that most of the people who are interested in him right now will move on to the next big thing soon enough. He marvels that the story of his Walmart paintings has been able to hold the public's interest this long.

Why have people from so many different media outlets and such divergent experiences with art been so interested in O'Connell's Walmart paintings? Neither contemptuous nor celebratory of Sam Walton's empire or the people who patronize it, the paintings are, rather, snapshots of ordinary scenes O'Connell has witnessed as he paints inside Walmarts around the country: bags of Wonder Bread stacked neatly on metal shelves. Busy check-out lines with glowing lights. A blonde woman in a candy aisle, her back to the viewer as she contemplates her purchase.

O'Connell suspects that the reason for the interest in his Walmart paintings is the same reason why he himself has been so fascinated with the mega-chain for the past eight years. Walmart is such a ubiquitous presence in American culture that it can serve as the medium through which we experience various states of feeling; it can also be the screen upon which we project certain emotions and have them reflected back to us. The availability and presentation of so many brands and items on Walmart's shelves, says O'Connell, provoke a sense of attachment and nostalgia among the people who shop there. Whether they're conscious that they are doing something more profound than picking up Jif peanut butter and Tide laundry detergent is irrelevant; the items shoppers are buying at Walmart may be utterly mundane, but they are attached to core life experiences.

"I feel like I'm painting cold things in a warm way," O'Connell explains. "Nostalgia makes memories warmer."

The themes O'Connell is exploring in his Walmart paintings have been on his mind for a long time, according to professors who knew him well when he was a student at Emory. Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Philosophy Thomas Flynn, who considers O'Connell "a close personal friend," recalls that as a student, O'Connell was remarkably authentic, "genuinely creative," and morally and aesthetically sensitive, preoccupied with ethical questions in a way that set him apart from his peers. Patricia Penn Hilden, who was also O'Connell's professor in the Department of Philosophy (and who has since moved from Emory to the University of California, Berkeley), shares similar recollections.

Catskills 1, 2011, acrylic on canvas

Courtesy Brendan O'Connell

"He was a wonderful student, intellectually curious, socially conscious, and very smart," says Penn Hilden, who, like Flynn, considers O'Connell a friend and has maintained close contact with him over the years. Both Flynn and Penn Hilden say they are not surprised to see him exploring existential themes in his artwork, and they are pleased to see O'Connell's talent receiving the kind of recognition it deserves.

There's another reason why O'Connell's Walmart paintings may have such broad appeal: the products visible in his work are immediately recognizable. This is not the case with the subjects of his abstract paintings and portraits, which comprise about 50 percent of his work. These haven't been mentioned in any of the profiles done about O'Connell to date, although that doesn't particularly bother him. The familiarity of the subject of the Walmart paintings makes that work more accessible to a wider, more diverse audience than is often the case for other forms of contemporary art.

"Art has become too rarefied, and most artists can't connect with more than a handful of people," O'Connell says. "Ultimately that's what interests me: connecting not with ten people, but with millions of people."

O'Connell, who is not represented by a dealer or a gallery, feels the art world has become largely inaccessible to people who lack disposable income and based on a transactional system that generally fails to benefit artists. His work has been shown in galleries, but with the Walmart series, he senses the potential of reaching a whole new audience—not to sell work, necessarily, but to inspire.

Though he has been painting in and about Walmart for almost a decade, O'Connell doesn't feel that the subject has become tired for him, and he doesn't plan to abandon the big box's aisles anytime soon. In fact, he wants to take his Walmart work to another level, one where he can "have real interactions with everyday people." That may well be possible, given that his own relationship with Walmart's management has improved since he first started photographing the stores surreptitiously in 2003. Back then, he says, he was regularly asked to leave, as he was violating the company's policy prohibiting in-store photography. Now, Walmart is O'Connell's willing collaborator on several projects, including his plan to take art to Walmart shoppers who may not have much access to it.

The idea, he says, "is to go to a place where there's not a museum within a hundred miles, set up a canvas the size of a window, and paint for three days in the [Walmart] store for people who have never been to a museum or a gallery."

Another of O'Connell's personal ambitions these days is to help people tap into their own creativity, which he views as a life skill. That's the motivation behind two other big projects on O'Connell's horizon: everyartist.me, a program targeted to kids, and Creativity Conversations, a short-term residency he has accepted at Emory that is scheduled to take place in early 2014.

Driven by what he feels is a "creativity crisis in our culture" and the experience, with Buchanan, of trying to foster creativity in their own kids, O'Connell spearheaded everyartist.me, which he describes as "the largest national art experience ever." The initiative, which will have its first iteration this fall, was tested last year in Arkansas with the financial support of the Rubin Foundation and Walmart Visitor Center, and was presented by O'Connell at TEDxAtlanta in September 2012. The aim is to have one million children across America form part of a social network in which they start "flexing their creative muscles." Kids can upload photos of their artwork via the everyartist.me app, which runs on any smartphone; submissions will be collected and pieced together before being projected digitally on a national icon, say, the Washington Monument or the National Gallery. O'Connell hopes that the scale of everyartist.me will inspire a national conversation about the importance of the creative arts in curricula, including at the university level. He also hopes that participation in the project will serve as an invitation to engage in lifelong creativity.

O'Connell plans to bring a similar message to Emory when he arrives on campus in February for Creativity Conversations, a program organized by the College's Center for Creativity & Arts. The center's series has included a who's who of literary artists, including writers Natasha Trethewey, Salman Rushdie, Billy Collins, Alice Walker, and Rita Dove, and musicians, including the renowned composer Phillip Glass and Atlanta favorite Emily Saliers 85C of the Indigo Girls. O'Connell will be one of the few visual artists to participate in the series to date. Although the details of his weeklong residency haven't been finalized just yet, the artist and alumnus is hoping to help students who aren't typically encouraged to express themselves creatively learn how to do so.

"I didn't even start drawing until after I graduated from Emory," O'Connell says, noting that the arts did not have a particularly strong presence at Emory when he was a student.

Leslie Taylor, professor of theater studies and the director of the Center for Creativity & Arts, says that while Emory's arts departments have been established for years, the university's artistic identity and culture really began to coalesce about a decade ago. "I think the construction of the Schwartz Center for Performing Arts in 2003 was an important catalyst," Taylor says. "The visible structure that said 'ARTS' on it helped change perceptions among people on campus and in the community, and that created a feedback loop. When people from the community began attending arts events, we were able to hold more events."

The fact that O'Connell didn't study visual arts at Emory is one of the reasons Taylor wanted to invite him back for Creativity Conversations. "He's a very interesting artist, so there are many reasons why we want to have him here," she says, "but the main one is that it's really important for students to see how their education at Emory prepares them for where life can take them, even when the subjects they studied aren't the professional paths they choose."

Beyond the conversation itself, which will likely be held with chemistry professor and department chair David Lynn, O'Connell is particularly interested in interacting with premed students, and envisions facilitating sessions where he will teach them how to draw. Learning such a skill isn't about becoming an artist, he says, but about developing flexibility, creativity, and the desire to connect with others— skills he considers critical for any career.

But he's not waiting passively for anyone else to come knocking. O'Connell clearly feels energized by the attention that's been directed at him since the New Yorker profile was published, and he's leveraging that attention to gain exposure and support for everyartist.me and the Creativity Conversations residency. He views the projects as initial steps in his mission to stimulate our collective creativity as a society. If he can start by helping students at his alma mater develop an interest in honing their visual literacy, he says, then he will feel satisfied.

And if he's successful, the next person to come knocking at O'Connell's door for fifteen more minutes of fame is anyone's guess.

Julie Schwietert Collazo 97OX 99C is a freelance writer living in New York City.

Email the Editor