Surprise Sleuth

Incidentally, an Emory curator unravels a mummy mystery

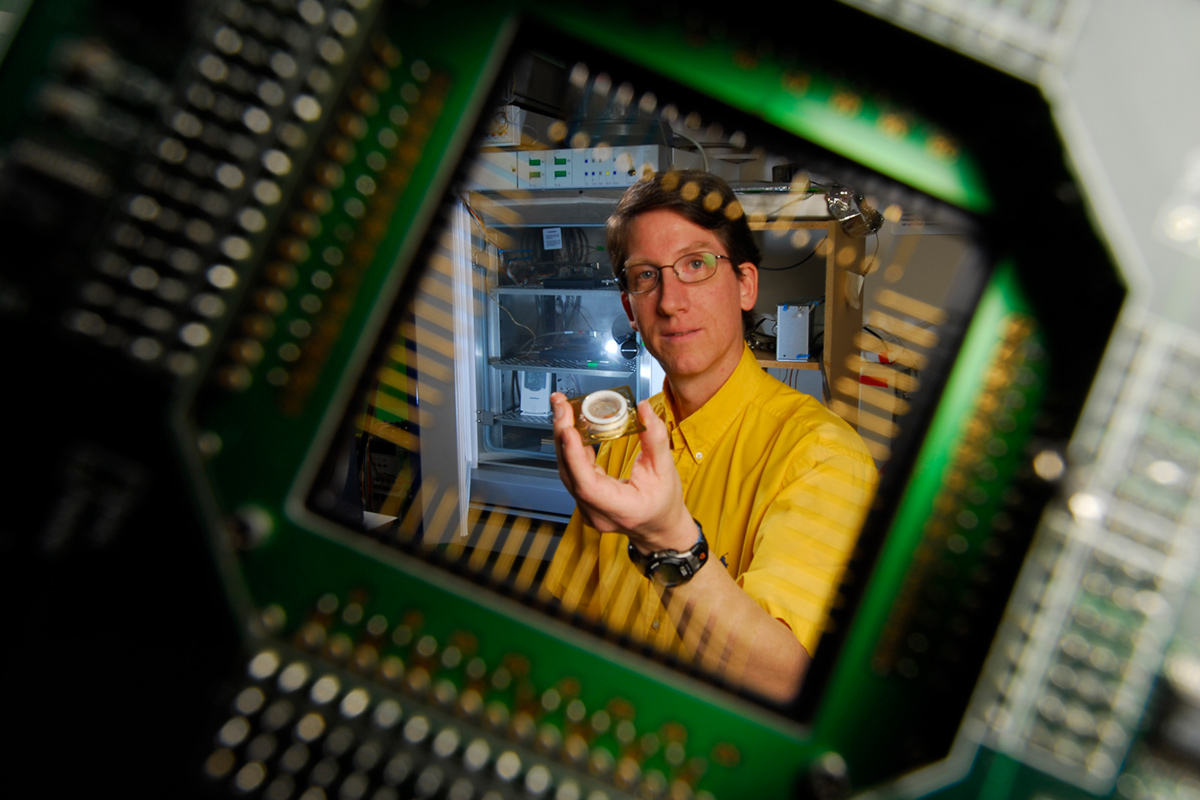

Peter Lacovara, senior curator of ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern Art at Emory’s Carlos Museum, has helped to solve plenty of mysteries. The well-known Egyptology expert is called upon frequently to apply his knowledge to deciphering and interpreting ancient civilizations.

But perhaps the most unusual mystery Lacovara solved is one he wasn’t asked to unravel.

Lacovara was technically off duty when he first visited Albany Institute of History and Art in Albany, New York, some half-dozen years ago. Established in 1791, it is one of the oldest museums in the United States, known primarily for its collections of regional significance, especially Dutch objects from the colonial period and Hudson River School paintings.

An obvious oddity in the otherwise New York–centric museum is a seventy-item collection of Egyptian antiquities, including two mummies acquired in 1909. The institute’s executive director, Tammis K. Groft, explains that the museum’s turn-of-the-century leadership believed any cultural institution expecting to command respect needed to have a mummy in its collection, so it dispatched board member Samuel Brown to Egypt, where he purchased two mummies and two coffin bottoms from the Cairo Museum.

The antiquities have been on continuous exhibit ever since, and they were what attracted Lacovara, who has a home in Albany, to the museum for his initial visit. But he never anticipated that the century-old mummy installation would become a professional preoccupation for the next several years.

“When I first visited,” Lacovara says, “I noticed that the wrong mummy was in one of the coffins. In a twenty-first dynasty coffin was a mummy of the Late Dynastic to early Ptolemaic Period, and beside it was a mummy wrapped in the style of the Third Intermediate Period that was appropriate for the coffin.”

Thousands of museumgoers had seen the mummies and coffins and been none the wiser. Lacovara, however, suspected a still-deeper mystery might exist. After talking with institute staff, Lacovara says, “I learned there had been [a switch] after the mummies had been x-rayed in the 1980s. The mummy that had been in the twenty-first-dynasty coffin of a priest had been pronounced a female, and the partially unwrapped mummy of a man was thought to have been the correct occupant. Errors have been made before in sexing mummies, and there have been tremendous improvements in CT scanning based on the Carlos’s work with William Torres of Emory Hospital.” Lacovara proposed that the institute reexamine the remains using modern technology.

When the mummies were scanned and x-rayed anew at the Albany Medical Center in 2012, not only did the scientists learn that the mummy thought to be female was actually male, they were able to discern specific physical characteristics that shed light on the mummy’s actual identity. “The owner of the coffin was a sculptor as well as a priest, an indicator that this was indeed the individual named on the coffin, Ankhefenmut, and its correct occupant,” Lacovara explains.

These discoveries alone would likely have prompted the institute to invite Lacovara to curate The Mystery of the Albany Mummies, an exhibit that opened this fall. But Lacovara had more in store. The coffins in which the mummies rested were incomplete, their companion pieces scattered around the world. Lacovara knew where they were, and better still, he knew the curators of the Vienna and London institutions where they were on display. He was able to get them on loan for the upcoming exhibit.

If this were a mystery novel, that would be a happy ending.