Loneliness, Transformed

Finding a Place at the Table

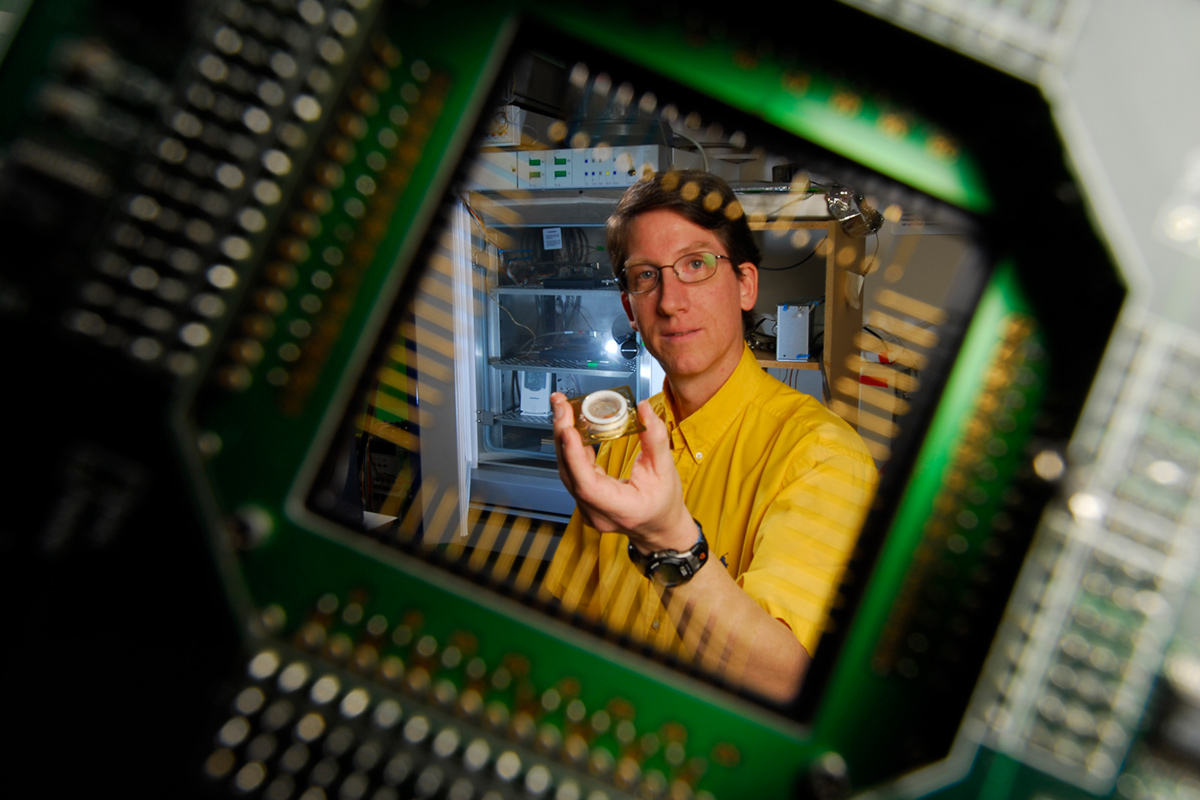

Kay Hinton

As a child in Virginia, I thought all food tasted delicious. After growing up, I didn't think food tasted the same, so it has been my lifelong effort to try and recapture those good flavors of the past.

If you grew up in Atlanta, or really anywhere in the South, chances are you knew some version of Bobby Banks.

As a boy, Bobby was that bright-eyed, loquacious kid whose very hunger for life—for schoolwork stars, for Boy Scout badges, for his mother’s love, for his church youth group, for his grandma’s homemade cakes—made him vulnerable; not to overt meanness or bullying, exactly, but to a childhood pushed a little bit aside from the other kids. Bobby’s character forms the heart of A Place at the Table, a new novel by Susan Rebecca White, lecturer in Emory’s Creative Writing Program

In addition to Coca-Cola, Bobby loves to help his mother and grandmother cook, and he loves being a Royal Ambassador, which is like being a Boy Scout—only better!—because the group’s activities are all conducted “in the name of Christ.” He especially adores Mr. Morgan, the group leader, who has green eyes and wears jeans instead of khakis like the other leaders.

If you haven’t figured out yet that Bobby is gay, he helps establish that early on. “I want a good friend, a best friend,” he says, his raw, innocent longing making sympathetic readers wince. “There are boys in the neighborhood I play with sometimes, but [his brother] Hunter’s always with us and that makes it not as fun. Hunter says I act like a sissy and then he starts pretending to talk with a lisp, and it’s not fair cause that’s not how I talk! It’s just that sometimes when I get really excited the words get jumbled up in my mouth and they don’t come out good.” It’s no wonder the cool kids give Bobby a wide berth.

As he gets older, Bobby learns to tamp down his natural effusiveness. But he never gets over his love of cooking, which is, in fact, the inspiration for his character. When this book—White’s third, written mostly during a difficult divorce—first began to take shape, all White really knew was that she wanted to write a kind of fictional homage to the famous friendship between Atlanta chef Scott Peacock and the late Edna Lewis, coauthors of The Gift of Southern Cooking, widely considered a modern classic. White’s mother had sent her the cookbook when she was living in San Francisco ten years ago, and she cooked dozens of its recipes out of sheer homesickness and a nostalgic yearning to taste her Atlanta roots.

Along the way, she became fascinated with Lewis and Peacock. “It was a story that seemed to counter so many stories about a country divided by race,” White says. “I wanted to write about a young gay man who becomes a chef, and his relationship with a black woman who’s fifty years older. Pundits dubbed them ‘the odd couple of Southern cooking,’ and I wanted to explore that idea further.”

Lewis grew up in a farming community of freed slaves in Virginia, where food was integrally connected to the earth’s changing seasons. She went on to hold a variety of jobs in New York before helping to open Café Nicholson, for years the legendary haunt of the city’s bohemian elite.

Like Lewis and Bobby Banks, White has loved to cook ever since she was a girl growing up in Atlanta’s Buckhead. “Food has always been this constant in my life, this thing that I can turn to when I feel overwhelmed by the world,” she says. “Buying local, not eating factory-produced meats, celebrating bounty—it’s a fundamental way that I can feel engaged in positive change.”

White was recently spotlighted in Atlanta Magazine’s “Home Plates” feature, which offers a window into how various “foodies” cook at home. That was a good indication of the book’s positive reception, which has ranged from star reviews to (even better, White says) a number of profoundly personal emails from readers.

While writing A Place at the Table, in 2011 White spent some time in New York, where there is an archival collection on Café Nicholson housed at New York University. She studied articles and reviews, photographs, menus, even matchbooks from the cafe. And she endlessly prowled the Eastside neighborhood where Café Nicholson occupied three different locations in its heyday, trying to channel the past. Thanks to a chance encounter with a doorman, she made an incredible discovery: that Johnny Nicholson, who co-owned the restaurant with Edna Lewis, was not—as she had presumed—dead.

“Not unless he died since I saw him two days ago,” the doorman said drily. Heart fluttering, White scrawled a note for Mr. Nicholson, now in his nineties.

She had nearly given up hope when Nicholson called three weeks later, inviting her for a visit that lasted three hours. “It was an amazing moment when life on the page met real life,” White says. “It felt like a huge gift.”

If A Place at the Table began as an intimate scene between two characters in the rarefied setting of Café Nicholson, the finished work is more like a sweeping montage featuring an ensemble cast. We meet the resourceful founders of a postslavery farming community, an enigmatic African American woman with an instinctual flair for food, a prominent scientist who controversially “passes” as white for most of his life, and perhaps most surprisingly, a desperately unhappy Connecticut housewife who takes comfort in fine food.

But one can’t help but feel that if White—now happily remarried and back to teaching at Emory—has a favorite child in this book, it is Bobby Banks, who after coming out as gay in New York, falling in love, and becoming a successful chef in a fictional (yet somehow familiar) cafe, begins to understand that he has left his home behind for good. Imagining a young woman trying to find her way around San Francisco and seeking solace in The Gift of Southern Cooking, one might catch a bittersweet whiff of what it feels like to really and truly grow up—a moment poignantly captured by Bobby when he realizes that his parents will never embrace his whole self again.

“A sadness like hunger spreads through my chest, and I try to distract myself from it by focusing instead on what I might prepare for Tuesday’s lunch special at the café. If I could find grits somewhere I could make Mama’s casserole with cheese and garlic. Serve shrimp on top. Dress it up with some basil cut in a chiffonade, maybe give it a fancy name—call it corn and crevettes—and serve it forth to the New Yorkers who will have no idea what they are eating, who will have no idea they are eating my loneliness transformed.”

A Place at the Table is a book about where you go when you can’t go home again—and about what you might eat for dinner when you get there.