Young at Heart

An innovative procedure adds treasured years

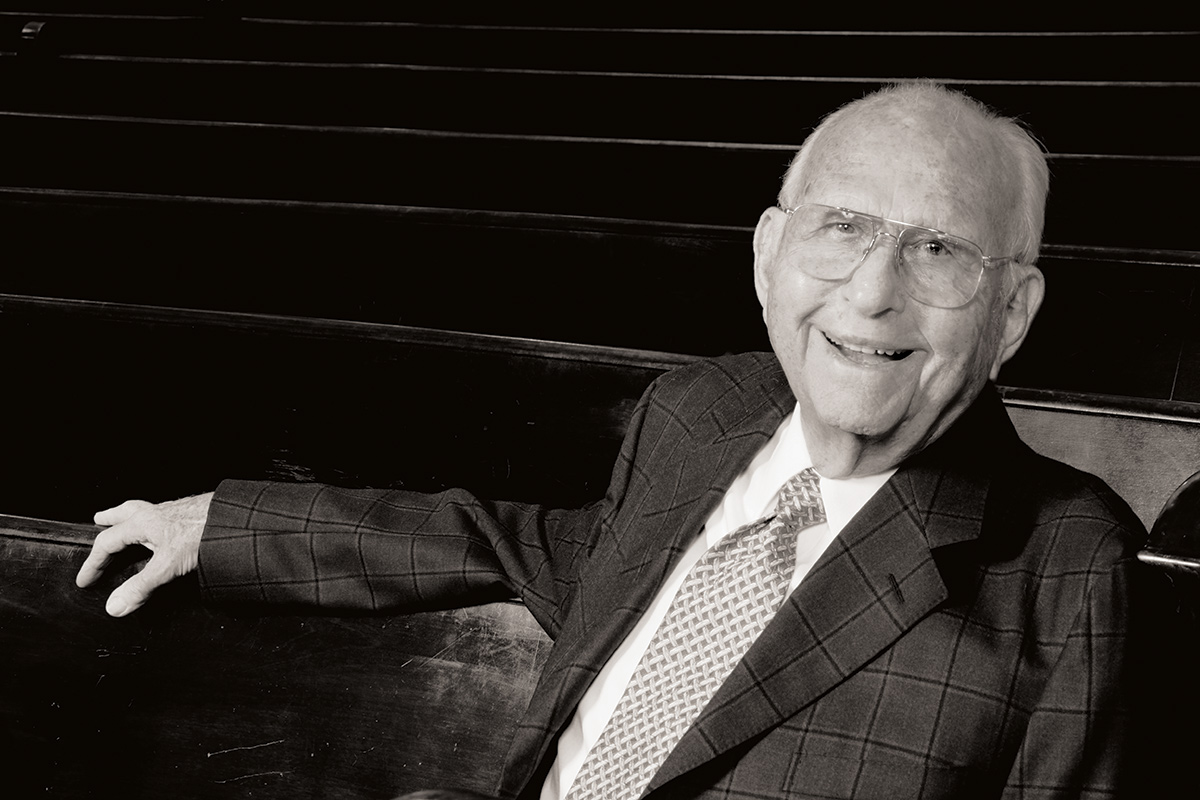

Courtesy of the Selby & Richard McRae Foundation

Richard McRae has always been a risk taker.

The retired Jackson, Mississippi, businessman built the McRae's dry goods store his father opened on Capitol Street in 1902 into a twenty-eight-store chain that anchored malls across the Southeast. He seized opportunities when he saw them, embracing new technology and ideas including adopting the early use of computerized cash registers and issuing gold cards to his best credit customers long before it became common practice with national credit companies.

In May 2011, at age ninety, McRae took part in a national clinical trial at Emory's Structural Heart and Valve Center for a revolutionary procedure called transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). McRae suffered from aortic stenosis—a narrowing of the aortic valve that results in restricted blood flow and debilitating strain on the heart—but was deemed too high risk for open-heart surgery because of his age.

At Emory, cardiac surgeon Vinod Thourani and interventional cardiologist Vasilis Babaliaros, codirectors of the Structural Heart and Valve Center, replaced his diseased valve with a new tissue valve using a catheter that delivered the device through his femoral artery to his heart. Once in place, the new valve moved the old diseased one aside against the aortic wall, allowing the blood to flow normally again.

Vasilis Babaliaros and Vinod Thourani

Kay Hinton

Just six months after the procedure, McRae was aboard a fourteen-day cruise through the Panama Canal, a trip he'd dreamed of taking all his life.

"The procedure has given him years he would not have had otherwise; good, productive years," says Susan Shanor 89L, McRae's daughter. "It has allowed him to continue to live independently and enjoy social activities." McRae turned ninety-two in February.

Aortic stenosis is the most prevalent valve disease in the United States, specifically in elderly populations, with approximately three hundred thousand cases. Like McRae, up to 30 percent of patients do not qualify for traditional valve replacement surgery due to age or other health conditions.

The first TAVR was performed at Emory in September 2007 by Babaliaros, Thourani, cardiothoracic surgeon Robert Guyton, and cardiologist Peter Block. Since then the Emory Valve Team has performed nearly six hundred procedures. Babaliaros, who spent several years abroad with the French cardiologist who successfully implanted the first catheter-delivered valve in 2002, learned the new approach and brought it to the United States and to Emory.

In addition to serving as national primary investigator for clinical trials for the third-generation Sapien 3 device currently being used for TAVR, Emory is "on the cutting edge for every new technology on the horizon" for the procedure, Thourani says. Emory will participate in clinical trials for three new aortic valve replacement devices in the coming months.

Emory's TAVR program is the third-largest in the United States, and the team has developed new solutions for the treatment of patients, including performing the country's first transaortic and transcarotid TAVR procedures using the SAPIEN valve. Moreover, they have the largest program in the country performing these procedures in the cardiac catheterization laboratory without general anesthesia.

"When patients come to Emory, they are not pigeonholed into one treatment for aortic stenosis. What TAVR has provided is another option for patients, which maximizes their chances for success. We have a range of patient-centered valve therapies, which minimizes risk of complications for each individual while optimizing outcomes," Thourani says.

Standard aortic valve replacement, with or without minimally invasive technology, is still performed when the patient's health allows and is the standard of treatment for patients considered low risk. For patients who are medium risk, Emory is the only center in Georgia and the third-largest in the country offering the second-generation SAPIEN XT valve.

Emory also is one of the first ten hospitals in the nation to offer the PERCEVAL sutureless valve replacement in an FDA-feasibility trial. This valve is designed to reduce the amount of time a patient undergoing traditional valve replacement surgery must be on a heart-lung bypass machine during open heart surgery, hopefully reducing the need for blood transfusion, length of hospital stay, and recovery time.

From left, Cardiology TAVR fellow Robert Leonardi, Vinod Thourani, Vasilis Babaliaros, and cardiac surgery TAVR fellow Sebastian Iturra review the placement of a new valve in a patient via ultrasound images on screens suspended in the operating room.

Kay Hinton

"We expect these patients to get back to an appropriate quality of life much more quickly with minimal complications," Thourani says.

Before his condition was diagnosed, McRae was socially active, enjoying movies and arts performances in Jackson, attending church regularly, and traveling around the country. It was on the eve of his ninetieth birthday, as he prepared for a celebratory cruise with his three children and their spouses, that his condition became acute.

"We all had traveled to Los Angeles, and we were leaving the next morning for the cruise," Shanor recalls. "That evening we were preparing to go to dinner, and Daddy collapsed in the hotel hallway."

An ambulance rushed McRae to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, where cardiologists identified his condition. By chance, the hospital was one of the national sites for the TAVR clinical trial, and one of the cardiologists discussed the option with the family. Shanor, an Atlanta resident, asked if there were any sites performing the procedure closer to her father's Mississippi home. The doctor referred them to Emory.

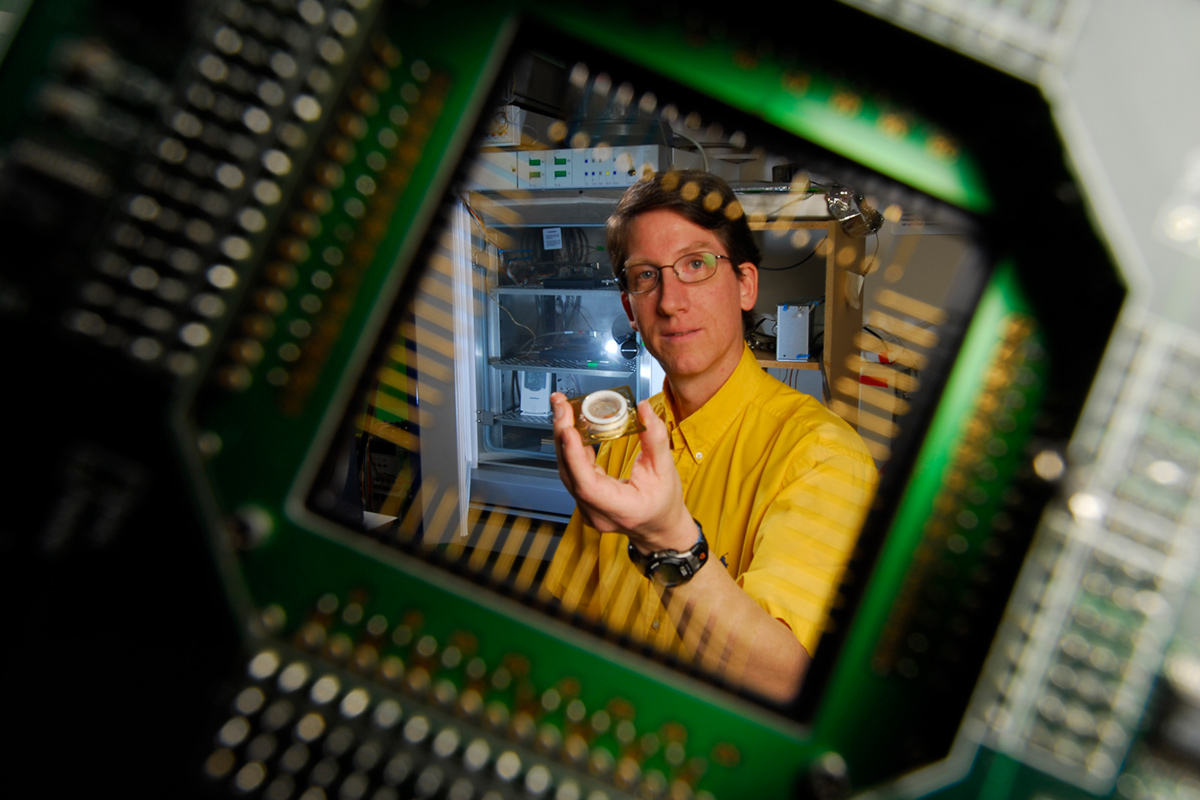

A surgery tech displays a new valve.

Kay Hinton

Shanor, whose husband, Charlie Shanor, is a professor at Emory's School of Law, contacted family friend John Puskas, an Emory cardiothoracic surgeon. He directed them to the Structural Heart and Valve Center.

"There was minimal recovery, and Daddy was back to doing things he loved so quickly," Shanor says.

Among those have been trips to New York City and Colorado, attending his youngest granddaughter's high school graduation in Atlanta, and enjoying his three great-grandchildren, including namesake Richard McRae IV. A lifelong equestrian, McRae also resumed his beloved hobby driving carriage horses.

Through the Selby and Richard McRae Foundation, which he established with his late wife in 1965, McRae committed $500,000 to support Emory's Structural Heart and Valve Center and the Emory Cardiothoracic Surgery Clinical Research Unit at Emory in honor of Babaliaros, Thourani, and Puskas.

"Because of the outstanding work and research of the team of cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons at Emory University School of Medicine, I am alive today," McRae says. "It is because of their countless hours of research and training that I was able to receive a heart valve transplant without having to undergo open heart surgery. I will always be grateful to the doctors for their outstanding care while I was at Emory."

Both Thourani and Babaliaros note that private philanthropic support allows Emory to continue to innovate in an era of cost containment and limited resources.

"Philanthropic support also allows us to train future physicians in this technically challenging procedure, furthering a growing field of expertise," Thourani says. "Emory is one of two sites in the country that now offers two fellowships per year in TAVR for physicians seeking specialty training in the growing field."