Brain Gain

Emory and Georgia Tech are a public-private powerhouse

You could say that Emory and Georgia Tech go way back.

The first president of the Georgia Institute of Technology was Isaac Stiles Hopkins 1859C, an Emory graduate who taught and also served as Emory president from 1884 to 1888. Hopkins was the ideal forefather of an institutional relationship that lends tangible meaning to the ubiquitous term interdisciplinary. He earned a medical degree, was a minister for eight years, then taught Latin, English literature, and various science courses at Emory; he also launched the first technology department in the state from his home, where students brought their own tools to experiment and learn. Emory’s technological program never really found its footing (or funding), but Hopkins’s initiative led to his recruitment as the newly established Georgia Tech’s president in 1889.

Current Emory President James Wagner and Georgia Tech President G. P. “Bud” Peterson chuckled over this shared chapter of history during a recent conversation in Wagner’s office. “When people ask, you know, you’re an engineer. When’s Emory going to start an engineering school?, I say, well, back in the 1880s, we did,” Wagner said. “And we’re very proud of it, and we’re not going to start another one.”

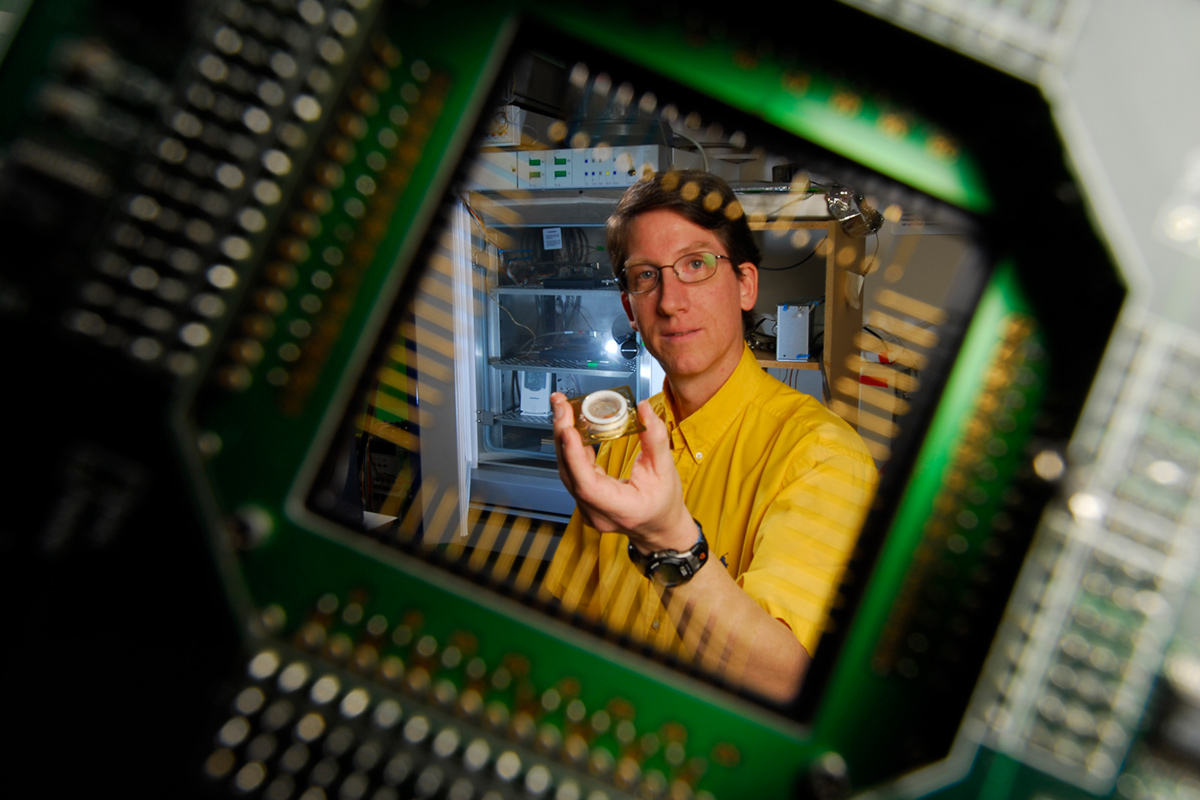

Nearly a century would pass, though, before the Emory-Georgia Tech partnership began to take concrete shape as a national blueprint for collaboration between a private and a public research university. The foundation of the partnership is in the area of biomedical engineering, where research interests are arguably most complementary. The Emory-Georgia Tech Biomedical Technology Research Center’s seed grant program began cultivating crosstown biomedical partnerships in 1987. Ten years later, the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME) at Georgia Tech and Emory was created—the first and still one of the few jointly run departments between a private and a public university.

“I think you and I were particularly lucky to inherit something that I believe is fairly unique,” Wagner told Peterson, who came to Georgia Tech in 2009. “The key may be the fact that it is complementary. Emory historically has not had strength in the engineering sciences, and we bring medicine and health sciences in a way that Georgia Tech hasn’t historically been engaged.”

“When people ask me what makes this partnership successful, the response I typically give is that we compete in almost nothing,” Peterson agreed. “You’re private, we’re public; when I ask our freshmen, how many of you applied to Emory?, a very small number raise their hands. We have different pedagogical interests, different types of institutions, and that, I think, is a real strength.”

Since the establishment of the Coulter Department in 1997—now ranked No. 2 in the country—the partnership has expanded in a number of directions that cross traditional academic boundaries, with joint research projects in areas including predictive health, regenerative engineering and medicine, nursing, ophthalmology, gerontology, public health, information technology, law, chemistry, and psychology.

As the research network grows stronger, so does both institutions’ ability to attract top-notch faculty and scientists, the presidents agree.

“When we recruit these top researchers, they are typically looking for opportunities to collaborate, and many of them find those opportunities through the clinical expertise in the medical school at Emory combined with the engineering strengths of Georgia Tech,” Peterson says. “The interdisciplinary nature of this joint program has allowed us to attract some really great people.”

The partnership attracts more than brainpower; it draws dollars, too. Last year, Emory and Georgia Tech each received more than $500 million in research funding and together spent nearly $1.25 billion on scientific research. That work, in turn, helps power the institutional engines that generate billions in economic output for Atlanta, Georgia, and the region. Emory’s last study put its direct and indirect economic impact at $5.1 billion; Tech’s, some $3 billion. In addition to that combined $8 billion financial boost, the two institutions support about fifty thousand jobs and have launched around a hundred thousand alumni now living and working in Georgia.

“That total eight-billion-dollar impact is owing in significant measure to the partnerships we have,” Wagner says. “If Emory were isolated and not partnering, there is a significant portion of our research portfolio— and all the people that supports, and all the expenses that are associated with that, and all the money that would come into the state—that we would not be eligible for without the partnership.”

Both presidents give credit to the Georgia Research Alliance (GRA), a nonprofit organization that helps funnel public funds to its six partner universities in Georgia with the aim of supporting and expanding research efforts, recruiting top scientists, taking discoveries to market through start-up companies, and building connections among the institutions. The GRA was a key player in the creation of EmTech Bio, a joint biotechnology incubator, in 2000.

“The partnership between Emory and Georgia Tech has been greatly facilitated by the GRA, because it provides a common pool of resources on which we can draw to help build the partnership,” Peterson says.

Nationally, public-private partnerships such as the one that has bloomed between Emory and Tech are relatively rare, says Barry Toiv, vice president for public affairs at the Association of American Universities (AAU), a Washington-based nonprofit dedicated to advancing the mission of research universities around the country. Emory and Georgia Tech are the only two Georgia institutions to have joined the prestigious ranks of the AAU’s sixty-two members—Emory in 1995 and Tech in 2010.

For public-private partnerships to thrive, Toiv says, it helps for the universities to be close to each other geographically and to have established, ambitious research programs that complement one another rather than directly competing. “Privates have the freedom of being private, and also frequently have greater resources,” Toiv says. “Publics bring the extraordinary relationships they have with government at all levels, as well as public resources, not just financial but other resources also. Those relationships can be very productive.”

He points to the University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University—both members since the AAU was founded in 1900—as one example, as well as the research triangle made up of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Duke University, and North Carolina State (which is not an AAU member).

“More than ever, North Carolina needs its top research universities to drive economic development. And to leverage their impact, those universities must join forces in unprecedented ways,” began an article in Carolina’s University Gazette in August of this year. “That was the message Joe DeSimone delivered to the University’s Board of Trustees last month.” The article went on to describe how DeSimone, the Carolina Chancellor’s Eminent Professor of Chemistry and a successful researcher and entrepreneur, made an impassioned case for partnerships that will attract research dollars and ultimately drive the recovery of the state’s flagging economy.

Many agree that’s exactly what happened in Pennsylvania, where the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University—two of the state’s four AAU member institutions—are literally across the street from one another. Their research collaboration played a major role in the revitalization of Pittsburgh after the region’s economy, long propped up by the steel industry, toppled in the early 1980s.

“In Pittsburgh, the strengths of Pitt and CMU have made this region an internationally respected center of cutting-edge academic work,” wrote Pitt Chancellor Mark Nordenberg in an op-ed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in January 2013. That partnership “has helped propel virtually all of the technology-based regional economic development initiatives launched in the past three decades.”

The synergy between Emory and Tech is creating similar momentum in Georgia. In just two decades, research collaborations have yielded more than seventy start-up companies and some sixty products in the development pipeline. The two schools have recruited more then thirty-five GRA Eminent Scholars and share upward of a dozen joint centers and initiatives. They also offer a PhD in biomedical engineering in partnership with Peking University in China. And plans are under way for shared library space at Emory’s Briarcliff location.

The two university presidents meet regularly and have an easy rapport, riffing good-naturedly on their respective football records (Emory remains undefeated, while Tech was 3-2 at press time). But while they are key facilitators of their universities’ relationship, they agree that its momentum now is unstoppable and its future a given.

“One of the delightful things that’s happened over the years is a sense of trust and possibility,” Wagner says. “By that I mean, rather than holding one’s cards really close . . . the history of the Georgia Tech-Emory partnership is such that I hope and I believe that it has opened up this sense of possibility for both of our faculties. I look forward to and imagine a number of new kinds of engagements through all of our schools.”