Just Blowing Smoke?

Fears of a 'crack-baby epidemic' look to have been exaggerated, but the impact of alcohol abuse on babies is not, says an Emory expert in prenatal drug exposure

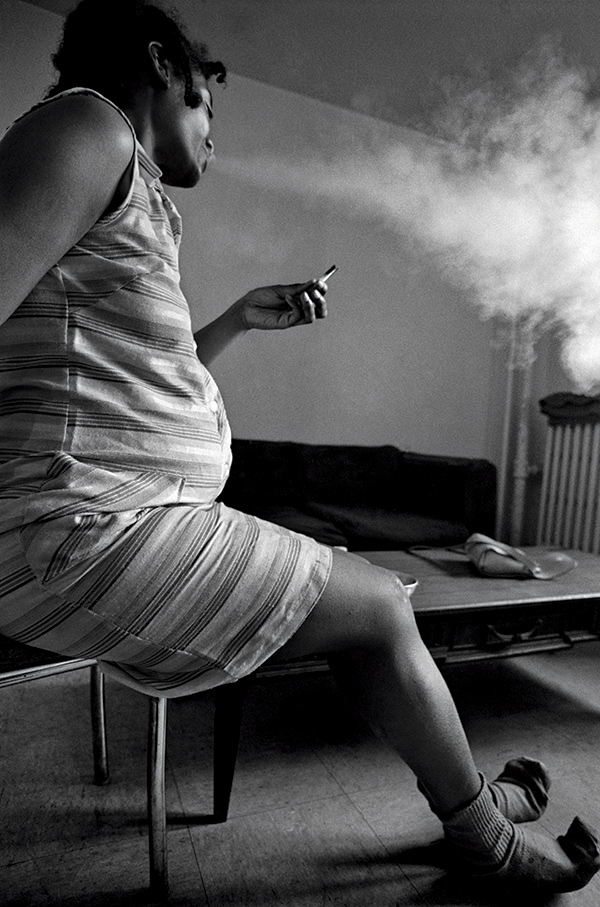

Retrospective: This photograph from the book Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue by photographer Eugene Richards shows a pregnant woman smoking crack in Brooklyn in 1988. The "crack baby epidemic" forecast to follow the surge of crack cocaine use in the 1980s never materialized, experts now say.

Eugene Richards

In the 1980s, the media began reporting on a new drug that was “taking over” America’s inner cities—crack cocaine. Doctors and other experts weighed in on the devastating effects this form of cocaine had on pregnant women and their newborns, which they said resulted in markedly higher levels of birth defects, mental and emotional disabilities, SIDS, and shaky, irritable, drug-addicted babies.

Hysteria about the so-called “crack-baby epidemic” spread. These damaged children were expected to overwhelm schools, social services, and societal safety nets with their special needs, ultimately creating a “new underclass.” Drug-addicted pregnant women were prosecuted as drug dealers, child abusers, even murderers.

Three decades later, most of these doomsday predictions have not proven true. Only subtle changes were observed in the brain of cocaine-exposed research subjects, many of whom successfully went on to work or college.

No particular evidence of widespread, severe social and emotional deficits has emerged, says Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Claire Coles 80PhD, director of Emory’s Maternal Substance Abuse and Child Development Program, who was featured in a recent “Retro Report” New York Times video, “Revisiting the ‘Crack Babies’ Epidemic That Was Not.”

Coles, who has long studied the effects of teratogens on behavior and development from infancy through young adulthood, was an early skeptic of the crack baby phenomenon after her own research didn’t back up the claims that were being made about babies born to cocaine-using mothers.

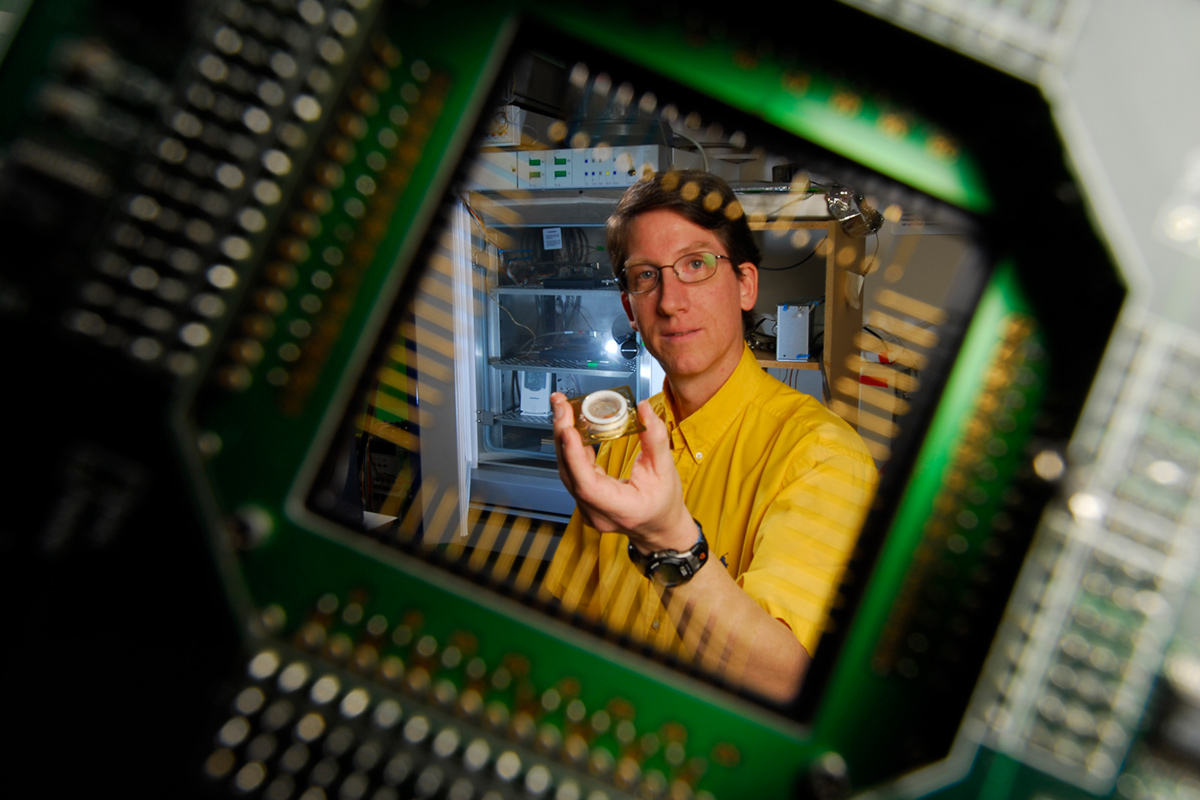

Claire Coles

Kay Hinton

“We’d seen the effects of alcohol and other substances on children, so we were certainly open to the idea that cocaine might be a problem,” she says. “But the effects didn’t seem consistent with the action of the drug itself.”

Cocaine, Coles says, is a stimulant, so cocaine-addicted babies, far from being agitated, would have been drowsy. “What you get when stimulants wear off is the crash, the system is depleted. You’d get sleepy babies,” she says. “What people were observing was the effects of prematurity on babies. Drug addicts do not tend to have good prenatal care; it’s not conducive to a good pregnancy. Preterm babies, in general, are thin and shaking and make quite dramatic television. You could have taken any premature baby and gotten the same image.”

To be substance-specific in addiction research is difficult, she says, since abusers often use multiple drugs “People got very focused that cocaine was the cause, instead of substance abuse, maternal lifestyle, social issues,” Coles says.

The initial research, which involved just a few dozen babies, should “never have been overgeneralized the way it was,” she says. In fact, cocaine exposure in utero appeared to have no effect on the IQ of the babies, but does have some lasting effect on the children’s abilities to self-regulate during periods of stress.

Coles, who works at Emory’s Briarcliff property, sees patients every week in the neurodevelopmental and drug exposure clinic, which keeps a database of thousands and focuses on treatment, prevention, and research.

Georgia provides funding to the clinic to do prevention work all over the state with schools and families, says Coles, who also works with hospitals in the Ukraine on drug and alcohol exposure during pregnancy.

Cocaine abuse peaked in the late 1980s, and now the trending substances are methamphetamines and prescription drugs—largely opiates, she says. While illegal drugs and many prescription drugs can be dangerous in pregnancy, the main substances abused by expectant mothers are cigarettes and alcohol, she says.

Smoking can result in low birth weight, preterm births, and problems with auditory processing.

“Alcohol, however, is more of a problem, and always has been. More alcohol is abused and there are much more severe effects,” says Coles, who began studying babies born at Grady Hospital in the 1970s during graduate school, and was one of the first researchers to identify and record the physiological characteristics of babies with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)—lower nasal bridge, bow flattened in upper lip, and small, “pinched” eyes. Babies with FAS also are usually impaired cognitively. “Neuroimaging of adults exposed prenatally to regular alcohol consumption shows very clear effects on the brain, distinct from those who were not exposed,” she says.