Seeking the Cells Where HIV Hides

Yerkes experts have identified new targets in HIV-infected patients already on antiviral treatments

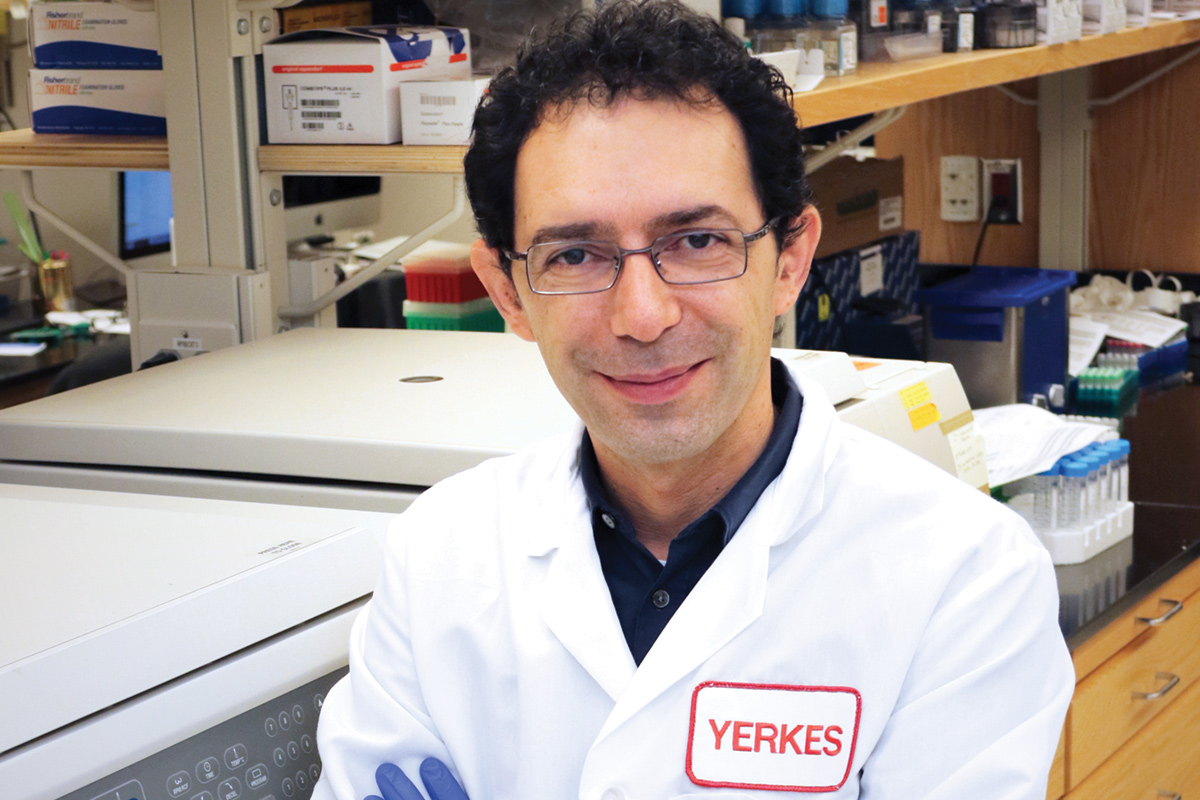

Courtesy of Mirko Paiardini

Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center have identified an additional part of the HIV reservoir, immune cells that survive and harbor the virus despite long-term treatment with antiviral drugs. The findings are published online in the journal Immunity.

The cells display a molecule callednCTLA4, the target of an FDA-approved cancer immunotherapy drug, ipilimumab. This information should help those trying to eradicate HIV from the body.

Researchers led by Mirko Paiardini, associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the School of Medicine and Yerkes and part of the Emory Vaccine Center, infected macaques with HIV’s relative SIV and treated them with standard antiviral drugs similar to what humans receive for HIV. At the time of analysis, eight out of nine of the animals showed undetectable SIV in their blood. The team probed for CD4+ memory T cells, which are known to shelter persistent virus.

“We found that a certain group of memory CD4+ T cells displaying CTLA4, but not another co-inhibitor receptor called PD1, harbor viral DNA at higher frequencies than other groups of memory CD4+ T cells,” Paiardini says. “These cells can be found in multiple tissues, such as lymph node, spleen, gut, and bone marrow, and contain replication-competent and infectious virus.”

Guido Silvestri, division chief of microbiology and immunology at Yerkes and a Georgia Research Eminent Scholar, is a coauthor of the study. The Yerkes team worked with researchers at NCI/Leidos Frederick, led by Jacob Estes, using a technique called “DNAscope,” to visualize latently infected cells in lymph nodes. Previous research had shown HIV-infected cells persist in regions of the lymph nodes called B cell follicles. The newly identified group of infected cells is found outside the B cell follicles.

Working in collaboration with Rafick Sekaly at Case Western Reserve University, the research team also showed the CTLA4-positive PD1-negative cells have the characteristics of regulatory T cells, whose job is to put a brake on the immune system and prevent it from getting too excited.

“It provides a strong rationale for targeting these cells,” Paiardini says. “Depletinglatently infected T-regs can not only reduce the reservoir, but also induce a stronger antiviral immune response.”

The researchers also worked with Vincent Marconi, a physician treating HIV in Atlanta, to confirm similar cells were present in human lymph nodes.

The human samples came from six HIV-positive individuals who had been on antiviral drugs for an average of three years.

Based on the team’s findings, Paiardini says, CTLA4 should be considered as an additional target when designing immunotherapies aimed at purging the viral reservoir.