Tracing the Footsteps of Emory's Indiana Jones

Kay Hinton

The Egyptian mummies, stone tablets, and ceramic vessels that first-year student Andrew Hoover 20C and his classmates were examining were millennia old and at least a century removed from the ancient tombs and sand pits in which they’d been found. Sitting in the gleaming cases and cool gray shelving of the Michael C. Carlos Museum, the objects were fascinating and exotic, mysterious save for the information typed onto their labels. What were the circumstances of their discovery? What efforts had gone into bringing them halfway around the world?

Providing that historical context was one of the goals of the fall 2016 course Hoover was taking. Exploring the Ancient Mediterranean through the Carlos Museum had been conceived by Professor Cynthia Patterson as a way to leverage the collection housed next door to show students how firsthand study of artifacts can deepen—or perhaps challenge—one’s interpretation of history gained through textbooks.

Many of the Carlos’s most significant pieces—including the oldest mummy in any American museum—had been brought from Egypt in 1920 by William Shelton, an Emory theology professor whose private journal and letters had been donated to the university in the 1980s. Almost as an aside, Patterson suggested to her class of undergraduates that Shelton’s papers could make for a worthwhile extracurricular research project.

“Sometimes in teaching, you just throw out hooks,” she now says.

Not long afterward, Hoover took the bait. A neuroscience and behavioral biology major on a premed track, Hoover had taken Patterson’s course because of his longtime interest in ancient Greece and Rome, but the Shelton detour piqued his curiosity. The Carlos Museum literature acknowledged that the professor had spent nearly a year traveling to Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel in a search for artifacts for Emory, but Hoover wondered about the details of Shelton’s experiences. This was just after World War I—was such travel grueling, even dangerous? And how does one go about buying a mummy?

So, Hoover stopped by the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library for a quick look at Shelton’s papers. In one of the first documents he reviewed, Shelton described in a journal entry how the expedition’s ship lurched to a halt on its way to Alexandria because a deadly Austrian naval mine left over from the war was spotted floating in its path.

“That’s what made me think that Shelton’s expedition was a lot more interesting than just a professor on a buying trip,” says Hoover.

Thus began Hoover’s own yearlong journey: applying for a university grant for summer study, spending hundreds of hours poring over more than 2,500 pages of Shelton’s letters and writings, meeting with Patterson to discuss how to interpret his findings, learning software coding in order to create an interactive online map showing Shelton’s travels, and, finally, delivering a presentation this past September playfully titled, “Emory’s Indiana Jones.”

Along the way, he followed the explorer’s exploits as Shelton described in his own words being captured by Syrian tribesmen, bribing an Iraqi warlord to provide safe passage through territory controlled by bandits, and visiting some of the most spectacular sites of antiquity—the Temple of Karnak and the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, the ancient cities of Ur and Babylon in Iraq, and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

“It felt a lot like a treasure hunt,” Hoover recalls. “His letters were a mix of family pleasantries and adventure tales”—punctuated by the occasional reference to a recognizable item in the Carlos collection.

Before he could launch his project, Hoover needed to obtain support. He had heard about the Summer Undergraduate Research Experience (SURE) program, which provides funding for students to continue their research full time over the summer months. Patterson helped Hoover put together a proposal that netted him a stipend and on-campus housing for ten weeks.

He is one of only about two hundred accepted each year by the Emory–run program, which also draws a select number of students from across the nation.

Patterson directs an interdisciplinary program called Ancient Mediterranean Studies, which takes a holistic view of the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, and the other civilizations that vied for power and survival throughout the region. Not only would a study of Shelton’s travels draw direct connections between many of the places studied, but it also would form a link between ancient and modern times as the explorer navigated his way through a fraught postwar landscape in which the fading European colonial powers struggled to exert control over chunks of the crumbling Ottoman Empire.

Handle with Care: "The Rose Library is wonderful in its encouragement of undergraduate research and the support it offers," says Professor Cynthia Patterson, who inspired Hoover to begin his Shelton project.

Kay Hinton

Instead of returning to his home in Jacksonville, Florida, Hoover spent the first half of the summer sequestered in the Rose Library for some ten hours a day. Like other researchers, he was allowed to request one box of documents at a time, supervised by staff. Pages must be turned over carefully, often while wearing gloves to keep oil or other contaminants off the fragile paper. He used his smartphone to scan each page and upload it to his laptop, where he would make annotations in the virtual margins. In the evenings, Hoover would go on Google Books to read Shelton’s long out-of-print memoir, Dust and Ashes of Empires, published in 1923.

William Arthur Shelton was a forty-five-year-old professor of Semitic languages at Emory’s Candler School of Theology when he was invited to join an expedition headed up by a friend, James Breasted, an eminent Egyptologist and University of Chicago professor who had recently founded that school’s Oriental Institute. While Breasted effectively had a blank check from the Rockefeller family to source artifacts for his institution, Shelton had the more modest backing of John Manget, a wealthy Atlanta cotton merchant and Emory booster.

“After the world war and the fall of the Ottomans, it seemed to many people like a good time to collect antiquities,” explains Patterson, who says the newly opened Mediterranean region was a little like the wild west—or, more properly, the wild Near East.

The expedition, grandly titled the American Scientific Mission, sailed from New York just before Christmas Day 1919 on a two-week transatlantic voyage. It was in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea when the ship encountered the stray mine. Shelton was alerted to the danger when he heard gunfire on deck from a crew member shooting at the explosive. “Our vessel was headed right into it and had we struck it we would perhaps have visited Davy Jones,” Shelton wrote home in a letter to his wife.

Arriving in Egypt in late January, the group headed up the Nile to Aswan, Luxor, and Abydos, which boast hundreds of royal tombs and prehistoric graves. Shelton would later write of walking through an ancient burial ground and seeing “grinning skulls sticking out of the debris, great mounds of broken pottery.” It was here that he bought his first mummy or, more accurately, a deconstructed set of mummy parts without a head—“just a bunch of rags and bones in a box,” says Hoover.

It wasn’t until nine decades later that radiocarbon dating confirmed that the body dated back four thousand years, making it the oldest mummy in the Western Hemisphere.

In Cairo, Shelton bought many of the 220 items that would form the core of Emory’s collection, including ceramics, statuary, sarcophagi, and two more mummies. Some of the acquisitions came from the Egyptian Museum, others from private antiquities dealers, and still others from less established vendors. When Shelton secured a purchase, he’d mail it back to Atlanta from the local American embassy.

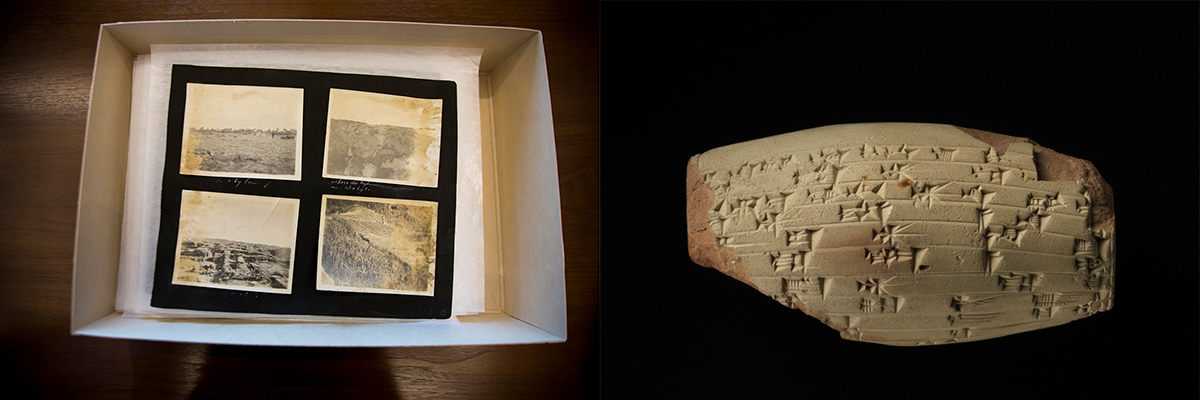

In the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh—now modern-day Mosul—Shelton acquired a small item that was to be one of his major finds, the clay cylindrical seal of Nabopolassar, founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and father of King Nebuchadnezzar. Then, outside Aleppo, the party was captured by armed Arabs who released them only after discovering they were American rather than the hated British. Sailing for London in late July, the expedition finally returned to New York in September 1920.

Physical Evidence: Photos from Shelton's journey (left) help provide context for artifacts like the Cylinder of Nabopolassar with Commemorative Building Inscription (right), which records the repair of the city wall of Babylon by Nabopolassar.

Kay Hinton

During his research, Hoover saw Shelton’s personal side: his excitement at finding choice artifacts, his reverence for Christian holy sites, his sincere wonderment at seeing the Great Pyramid and the Sphinx, and, surprisingly, his increasingly chilly relationship with Breasted—who also wrote dismissively of Shelton in his own journal.

Hoover also noticed a disconnect between what Shelton confided to his journal and the much rosier picture he painted for his wife. “His letters to his family are very relatable and personal, a mix of pleasantries and adventure tales” that omitted some of the near-disasters and narrow escapes, he says. On the other hand, his published memoir is much more formal and jingoistic as he repeatedly touts America as the greatest country on earth.

“Shelton remains something of an enigma to me, but I came to like him quite a bit,” Hoover says.

Once Hoover completed his research, he worked for several more weeks with two specialists with Emory’s Center for Digital Scholarship, art historian Joanna Mundy 19PhD and librarian Megan Slemons, to develop an interactive web page showing the route of Shelton’s journey to the Near East. At each stop along the way, users can click on the map to learn what Shelton saw and did at that location, read excerpts from his writing and see the photographs he took to document his travels. Hoover also embedded links to pages in the Carlos’s website that show images of items collected at each location—when that information is known. Because of relabeling of artifacts over the decades, he had some difficulty determining the origin of some pieces, even after tracking down Shelton’s original list of acquisitions.

Shelton’s journey has been traced before. In 1989, when the Carlos was still known as the Emory University Museum, it staged Monuments and Mummies:The Shelton Expedition. The exhibition included a video showing Shelton’s route, with excerpts from his journal narrated by Professor Emeritus Max Miller 64PhD, who’d been a colleague of Shelton’s at Candler.

“We’re hoping more work can be done to further Andrew’s work and recreate some of the excitement of Shelton’s journey,” says Elizabeth Hornor, the Carlos’s longtime director of education. “Without Shelton’s acquisitions, the Carlos would not be the museum it is today, and his diaries and photographs are a wonderful opportunity for student research.”