Fab 5

Meet a few of the Emory scholars who are blurring lines, bridging disciplines, and pushing boundaries

Kay Hinton

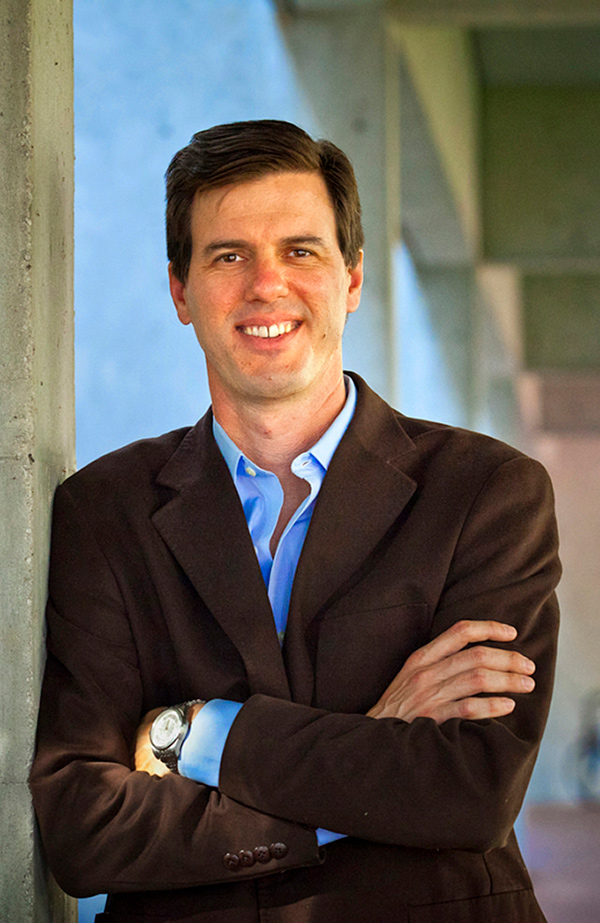

Joseph Crespino

Jimmy Carter Professor of Twentieth-Century American Political History and Southern History since Reconstruction, Department of History

A historian of twentieth-century America with expertise in the political history of the post-World War II era, his published work has examined intersections of region, race, and religion in US politics.

Long before Joe Crespino became a professor in Emory College of Arts and Sciences' Department of History, he read To Kill a Mockingbird as a middle schooler in Macon, Mississippi. Growing up in the 1970s in a town much like Harper Lee's fictional Maycomb, Alabama—where racial tensions were "very real and very palpable"—Crespino formed a singular attachment to the figure of Atticus Finch.

"You read this and you want to grow up and help your community and help your state—to grow up and be like Atticus Finch," Crespino says. "Most people who read the book realize at some point that Atticus Finch is not a real person and they move on with their lives, but I just kind of got hung up on that, I guess."

Though he eventually relinquished the idea of going to law school—one he still entertained while completing a history fellowship at Stanford University, where he earned a master's and PhD—Crespino remained captivated by the character, contemplating his complicated role not only in literature, but also as an influence on political culture.

Author of In Search of Another Country and Strom Thurmond's America, award-winning historical analyses that have been lauded for examining the origins of modern conservative politics, Crespino will publish Atticus Finch: A Biography in May with Basic Books. As the title implies, the book is a nonfiction history of the fictional character and his influence on modern politics.

"I've always been fascinated by the character, but also by the persistence of this book in popular culture," Crespino says. "It is like a primer for American middle school children, and children around the world, for values of tolerance and empathy and decency and what an important role they play in a multiracial society."

Although based on a fictional character, Crespino's biography scrutinizes Atticus Finch by examining the life and opinions of Harper Lee's father, Amasa Coleman Lee, who practiced law and served in the Alabama state legislature from 1926 to 1938 and was owner and editor of the Monroe Journal from 1929 to 1947. The elder Lee was a prolific editorialist, writing several editorials each week about politics at the local and state levels and addressing national and international topics, from the rise of fascism in Europe to the evolution of the New Deal.

"It was fascinating to read those eighteen years' worth of editorials, to be able to kind of recreate his political worldview and see how it shaped his daughter's," Crespino says.

Other primary sources included a collection of letters from Harper Lee from Monroeville in the 1950s to her friends in New York that were owned privately by a lawyer and rare book collector in San Diego, and correspondence between Harper Lee's editor at HarperCollins and various publishing houses.—Maria M. Lameiras

Michelle Wright

Longstreet Professor of English, Emory College Department of English

Wright has incorporated physics theory on time into her work on how "blackness" is defined, and has written on issues of black identity, blackness and sexuality, and racism in technology.

"Miss Recent PhD Wright has no business writing on these matters."

As Michelle Wright's first book, Becoming Black, based on her dissertation, was being evaluated by a publisher, those words stared back at her from an outside reader's report. She had been put on notice for her age and gender.

Going big quickly became Wright's signature as a scholar. "Becoming Black," writes Rebecca Wanzo of Washington University in St. Louis, "is an introduction to racialized Enlightenment discourse on subject formation, an overview of the most important black responses to these philosophies, and a feminist intervention into theories of diasporic black identity. Such an all-inclusive project could easily be unwieldy, but Wright demonstrates mastery of her subject matter and reveals how the integration of these textual histories is a necessary foundation for scholars of the black diaspora."

The daughter of an African American father who served in the diplomatic corps and a Czech-Polish American mother who was a schoolteacher, Wright was educated abroad until high school. When it came time to enter Woodrow Wilson High School in Washington, Wright was afraid of being harassed for "talking white or acting white."

Her parents did not discuss race, feeling that to do so only made it worse. They married in the late 1950s, at a time when interracial marriage still wasn't legal everywhere. "In a way," says Wright, "their reticence to speak about race worked for me because then I was on my own to figure things out."

During her first year of graduate school, Wright encountered Patricia Hill Collins's Black Feminist Thought. "I learned that my experiences and identity are actually worthy of thought and reflection," she says. "Then, as now, it is rare to find a scholarly book about black women."

In the research that led to her second book, The Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, Wright got interested in questions such as, Does the meaning of blackness change over space and time? Rather than seeing blackness as a "what," isn't it a "when" and a "where"? She is drawn to such topics because of the payoff—that "you are forced to rethink almost everything." The book challenged Middle Passage epistemology, the dominant narrative of African diasporic identities that reduces the complexity of blackness in the West by stressing the process of being captured in one world to be forcefully brought into another.

Wright's book has been the topic of panels at two major scholarly conferences, and she has run workshops on how to approach scholarship with this more inclusive notion of blackness.

Believing that there is no "flawless ideology," Wright reserves the right to investigate anything, even long- or deeply held ideas. As she comes to any new project, she observes two rules: "Step back. Throw your arms open." It's advice that has served her well so far.—Susan Carini 04G

Rohan Palmer

Assistant Professor of Psychology, Emory College Department of Psychology

Palmer studies genetic and environmental factors related to substance addiction. He recently received an NIH Pioneer Award from the NIH National Institute of Drug Abuse.

As an undergraduate, Rohan Palmer worked in a lab observing whether female mice could overcome their anxiety to leave the safety of the nest and retrieve babies that he and other researchers had moved away.

Intriguingly, the study showed that some strains of mice performed differently from others in overcoming their emotions to perform their motherly duties. Moreover, females exposed to more testosterone in the uterus performed worst at this and other maternal tasks.

"It was understanding behavior at its core," says Palmer, assistant professor of psychology in Emory College. "What helps us understand what makes us individuals better than looking at the environment and the biology?"

Palmer's new focus on that question is among today's most pressing: What makes some people addicted to drugs or alcohol, and not others?

His innovative approach, to find and characterize the layer of biology on top of factors such as environment to find an answer, has earned him a 2017 Avenir Award for Genetics or Epigenetics of Substance Abuse Disorders from the National Institutes of Health Director's Pioneer Award program. The five-year, $2.34 million award is among a handful of grants given to recognize "highly creative" scientists from the nation's top universities and to encourage high-impact approaches to the broad area of biomedical and behavioral science.

"This is a special award, more so because very few beginning investigators receive this honor," says Ronald Calabrese, the college's senior associate dean for research.

Palmer's work aims to understand how genetic differences contribute to a generalized vulnerability to addiction, first by studying existing DNA samples from hundreds of thousands of people who self-report drug use or those being clinically treated for addiction.

Pinpointing regions in the human genome that confer susceptibility to addiction is just the first step of this novel project. The complexity of this behavioral genetic approach then integrates evidence across multiple species that have been or are being studied elsewhere to prioritize specific genes that explain addictive behaviors.

With that, Palmer will be able to develop a predictive model—available to other researchers, not for commercial use—to infer genetic risk for substance abuse.

"For me, behavioral genetics is all about understanding people," he says.

Palmer's "MAPme" project, planned to launch in the fall, will follow a subset of first-year students for a year in order to understand how patterns of drug and alcohol use relate to a person's psychological well-being, personality, genetic profile, and level of cognitive functioning.

"The unanswered question over all of this is what's really happening in people over time," Palmer says. "Do people drink more because of poor impulse control, poor memory, or genetics? As we are able to put together the genetic factors and the environmental factors for these and other drug-related behaviors, we may know."—April Hunt

Jaap de Roode

Associate Professor of Biology, Emory College Department of Biology

Research interests include the ecology and evolution of infectious diseases. He currently studies infectious diseases of monarch butterflies, honey bees, and humans.

Jaap de Roode pays attention to the little things. Like, bugs. Specifically, how they use natural substances to keep themselves alive.

Take monarch butterflies. In 2010, de Roode, associate professor of biology in Emory College, made the significant discovery that monarchs use toxins found in milkweed to cure themselves and their off spring of parasites.

Learning how insects and other animals use plants and other materials to self-medicate is important, he says, because it has "direct implications for human health and food production."

"Yet most people will just see an insect and call their pest control agency and move on, and that's it. What they're missing is this beautiful understanding of these creatures," he says.

Until a little more than a decade ago, primates were among the only animals besides humans thought to have the capacity for self-medication. Chimpanzees, for instance, had been observed in the wild eating plants with antiparasitic properties but with little or no nutritional value.

Then some birds were found to line their nests with plants that ward off parasites, fungi, and other pathogens. Ecologists in Mexico published a study suggesting that house sparrows and finches may be studding their nests with cigarette butts because nicotine reduces mite infestations. And the evidence for self-medication is even stronger in insects.

"It's now clear that animals do not have to have a big brain or advanced cognitive skills to use medicine found in nature," de Roode says. "We're seeing that these behaviors can be innate."

During the past fifteen years, these ecological and evolutionary findings have changed how scientists approach infectious diseases among humans, wildlife, and livestock. But de Roode is worried about bees.

In the US, managed honeybees are vital to the production of more than half of the leading crops for human consumption, including fruits, nuts, seeds, and vegetables. But colonies are declining by between 30 and 40 percent annually. Drought, pesticides, viruses, and other pathogens are all potential causes, and commercial beekeeping practices are helping them along, according to a paper recently coauthored by de Roode and published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

For example, in the wild, some honeybees mix their saliva and beeswax with tree resin to form what is known as propolis, or bee glue, to seal holes and cracks in their hives. The substance helps keep diseases and parasites from entering the hive and inhibits the growth of fungi, bacteria, and mites. Yet bee farmers tend to select insects that don't produce these resins because they are more convenient to manage, but may have behavioral deficiencies that make them less fit.

One possible solution is to support bees' natural behavioral resistance to disease and parasites.

"Propolis is sticky. That annoys beekeepers trying to open hives and separate the components so they try to breed out this behavior," de Roode says. "But given the antiparasitic properties of propolis, beekeepers should consider reintroducing this trait in their honeybees."—Carol Clark

Erin Tarver

Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Oxford College

Tarver specializes in feminist philosophy, American pragmatism, and poststructuralism with particular interest in the relationship between popular culture and the self.

You might say Erin Tarver is self-motivated.

As a philosopher, Tarver, assistant professor of philosophy at Oxford College, has always been interested in the deepest questions surrounding human identity. How well do I really know myself? Can I ever be sure? Am I truly a good person, or do I merely appear good on the outside?

Tarver's own identity was shaped early on by some of the most powerful forces in American culture—the deep South, church, and football. Raised in Baton Rouge in an evangelical Christian family, Tarver's childhood was dominated by LSU football games—the Christmas-like anticipation of each weekend, the elaborate game-day rituals, and the tidal waves of shared emotion that surged through thousands of Tigers fans with every yard gained or lost.

Later, in graduate school at Boston College and then Vanderbilt, Tarver would revisit those experiences as she sought to master the texts of ancient philosophers— Cicero, in particular, "raised the question of whether I could be absolutely certain of who I was or if I was misunderstanding myself," she says. She also began to grapple with profound questions about race and gender, acknowledging her own privilege for the first time. That's when she began to consider the American sports industry and its impact on individual identity in a new way.

"For people who are devoted sports fans, I'm suggesting that those practices are integral to making them who they are," says Tarver, who published her first book, The I in Team: Sports Fandom and the Reproduction of Identity, last year. "When Auburn fans say they bleed blue and orange, they are saying something not too far from the truth. The practice of being a fan is a central feature of their being the human being that they are."

The book also explores the impact of sports fan frenzy on athletes, like college and professional football players, who—if they're lucky—make a lucrative but short-lived career out of entertaining stadiums filled with roaring mobs at grave personal risk.

And another thing. "Sport is perhaps the most rigidly gender-segregated arena of public life, and one of the most strongly racialized," Tarver says. "I came to realize that these things I grew up loving were, in many cases, deeply unjust. How much of my own experience of self as a young woman was caught up in the exploitation of these young men, mostly men of color? It's a normal human desire to have these rituals, but there are other ways to achieving that goal that are less destructive."

Tarver probed these themes in a New York Times op-ed published last year, where she challenged fans to consider whether they treat the players they cheer for as human beings, or as mascots. Not long afterward, she was contacted by former NFL player Alan Grant, who confided that the question resonated for him. This semester, Grant will Skype in to Tarver's Oxford class as a guest lecturer on the philosophy of sport—bringing his experience, his expertise, and of course, himself.—Paige Parvin 96G