The Rainbow Chronicles

How Emory is preserving the history of civil rights across social movements in the South

Moving from suburban Cleveland, David A. Lowe 92C was looking forward to a change—a different part of the country, better weather, a new intellectual environment—when he enrolled at Emory in fall 1988. He had no idea how much his presence would change the university.

As an openly gay freshman, Lowe attended a meeting early that first semester of the Emory Lesbian and Gay Organization (ELGO) and was met by a very small group of about a dozen people who, he says, held occasional meetings and social activities, but little else. But then things started to get interesting.

“We started getting more active and visible, speaking at freshman dorms and organizing campus events. At some point, ELGO invited a guest speaker from ACT UP Atlanta, and I was just blown away. In the suburbs where I grew up, the AIDS crisis wasn’t talked about and gay issues in general were rarely discussed and there was not much activism. I found it refreshing that there was this group of people being vocal and being active and engaging with the media,” Lowe says. “I thought, ‘This is what the LGBT community should be doing,’ not just with respect to AIDS, but in politics and on social issues.”

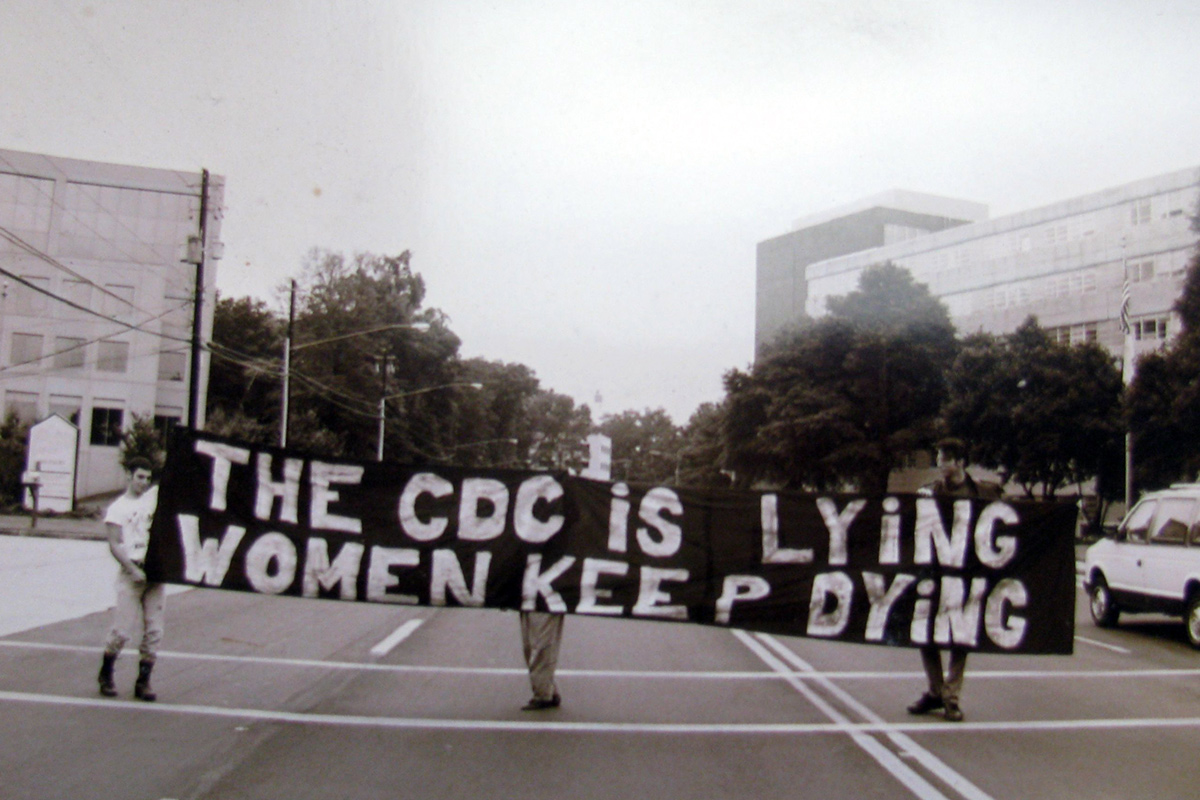

ACT UP protestors

Lowe began participating in ACT UP meetings and community events—including several AIDS protests, and subsequent arrests, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), CNN, and the state capitol—and brought that energy back to Emory. He started working with others in ELGO to increase visibility and engagement on campus; building awareness of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) student needs; and advocating for increased resources.

During his four years at Emory, Lowe saw growing recognition of LGBT issues on campus—including advocating for the establishment of the university’s Office of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Student Life (now the Office of LGBT Life)—accompanied by a groundswell of new LGBT organizations on campus and growing influence among Emory’s LGBT community. By his junior year, acceptance of gay and lesbian students on campus had progressed so much that Lowe narrowly lost election as SGA president as an openly gay candidate.

Lowe collected many mementos of his activities that he took with him when he moved to California for law school and to San Francisco as he built his law career.

“I had a close friend working with the LGBT Historical Society in San Francisco, and I initially asked if there was anything I had from Atlanta that would be interesting to them,” Lowe says. “He told me that it was regional history that really belonged in the place where the history unfolded.”

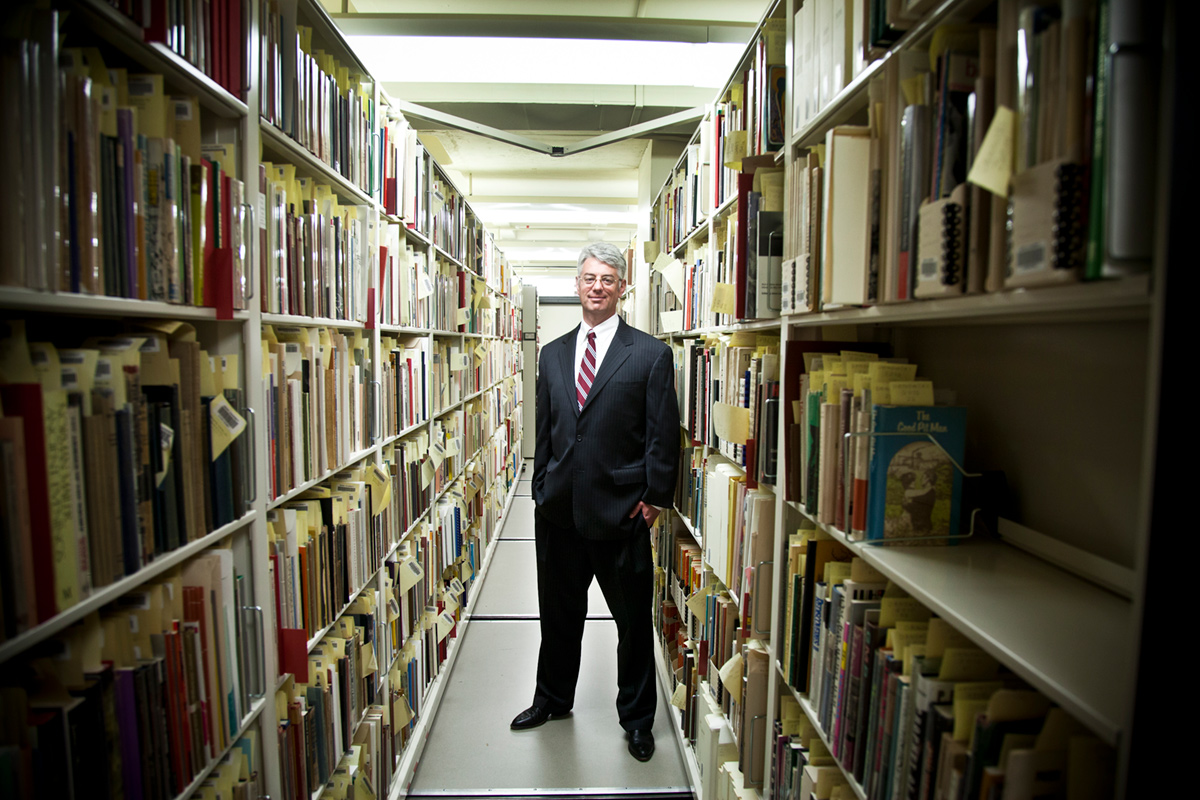

Meanwhile, at Emory’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Randy Gue 94G 97Gwas familiarizing himself with the library’s collection as the new curator of Modern Political and Historical Collections. An Atlanta historian, he was eager to build on MARBL’s strengths in chronicling “communities that were once at the margins of society and are now a part of the national mainstream,” including special collections focusing on Southern history and culture, African American history and culture, the civil rights movement, and the works of Irish poets and authors.

“That history of disenfranchisement ties all of these disparate collections together. These collections follow a path of civil rights and human rights struggles that is one long, continuous line. Civil rights, the struggle for social justice, and human rights are common throughout all of these areas. It is the same struggle in different ways and in different arenas,” Gue says.

As he looked at Atlanta’s history in the years after the civil rights era, he saw the emergence of another marginalized population that began to emerge as a national force for change.

“Beginning with the gay liberation movement of the early 1970s and followed by the activism that grew out of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, the LGBT community had more visibility than before,” Gue says. “It was a remarkable transformation from an almost invisible population to one that was a major part of the historical conversation. There was no way to move the timeline of our collections about Atlanta forward without including these communities, their voices, and their histories.”

Although MARBL had LGBT materials in its collections already—video archives from Network Q, a video magazine that ran in the 1980s and 1990s, and the records of the Southeastern Arts, Media, and Education Project (SAME), which was founded by lesbian playwright Rebecca Ranson—Gue knew he needed to reach out to the LGBT community for help in identifying more.

In 2011 he attended a town hall meeting on the Georgia LGBTQ Archives Project, a joint effort of various community, governmental, and educational organizations to preserve Atlanta’s gay history and archives. There he met Atlanta activist Jesse Peel, a pivotal figure in the gay community’s response to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s.

“That first meeting with Jesse was literally like throwing a rock into a pond. The circles in the community have gotten bigger and bigger and have just kept going,” says Gue.

The library is now collecting in a systematic manner and, more than simply preserving and storing the materials, Gue intends to foreground interconnections between the materials of individuals and organizations that could potentially be lost with time.

“As we are doing this, what we have in mind is the graduate student who will be using these materials 150 years from now. How can we organize these collections so they will not be seen as a bunch of archives from individual activists or organizations doing unrelated things, but as pieces of a larger history?” he asks. “Most of the people who have donated materials have known each other, and by bringing these together, instead of lots of little conversations, there is now one large conversation going on.”

While Peel and his contemporaries serve as mentors in the LGBT community, a new generation is taking up the torch when it comes to gay rights. Michael Shutt, assistant dean for campus life and director of the Office of LGBT Life at Emory, says the university has generated many of these new leaders.

“When I think of the impact Emory has had on LGBT issues, it is incredible. Not only the work that Emory has done in HIV and AIDS research, but our alumni,” he says, ticking off a sampling of the many alumni who have gone on to influence the Atlanta LGBT community—Saralyn Chestnut 94PhD, first director of Emory’s Office of LGBT Life; Sara Luce Look 92C, owner of feminist bookstore Charis Books & More; musicians Emily Saliers 85C and Amy Ray 86C of the Indigo Girls; Laura Douglas-Brown 95C 95G, founder of Georgia Voice; Scott Turner Schofield 02C, an award-winning performer and speaker on transgender issues; Aby Parsons 13G, inaugural director of Georgia Tech’s newly formed LGBTQIA (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning, Intersex, and Asexual) Resource Center.

“These are Emory people. They are products of the Office of LGBT Life and the work they started here. I think Emory’s commitment to LGBT issues and preserving LGBT history has brought these people back into the Emory fold, and that is a really powerful thing,” he adds.

“Out from day one” of her freshman year at Emory, Douglas-Brown befriended classmates Michael Norris 95C and Alfred Hildebrand 95C, two gay students who became pivotal figures in LGBT rights at Emory. The young men were harassed in a residence hall after other students observed them kissing in a study area. The incident led to a formal complaint to the administration, a high-profile protest including a “kiss-in” at the residence hall, a rally at Dobbs University Center, and a sit-in at the president’s office. Douglas-Brown was there for all of them.

“I remember being so frightened the day we were going to march to the president’s office, because I was here on scholarship. I thought they would take it away from me,” says Douglas-Brown, who has recently returned to campus as editor of Emory Report, the university’s faculty and staff newspaper. “We were all sitting out in the hallway outside of President [James T.] Laney’s office while he met with our representatives. It was a very Emory moment because they came around and served us all Cokes. The administration listened to what we had to say and took our concerns seriously. That experience was fundamental for me in that it shaped who I wanted to be in the community. I saw myself as an activist.”

Maybe it was the Coca-Cola; more likely it was the attitude of respect. The incident influenced Douglas-Brown’s decision to remain and work in the South.

“Here was this huge institution—in the South, with religious ties—and they were doing their best to change,” she says. “The changes that happened over the next few years at Emory were dramatic, and they informed my belief in change.”

After graduating from Emory, Douglas-Brown became an intern at Southern Voice, the LGBT newspaper for Atlanta and the Southeast founded in 1988. She remained, eventually rising to editor, until Southern Voice closed its doors in November 2009. Just four months later, with the backing of community supporters, she helped launch Georgia Voice, an LGBT-oriented biweekly still in operation.

As a journalist, Douglas-Brown appreciates the importance of chronicling the history of the LGBT community.

“That was something that scared us at Southern Voice before it closed. What if something happened to our archives? So much of a community’s history is tied up in publications like that,” she says. “It is exciting to see MARBL collecting these things and knowing they will be preserved. These materials matter.”

Emory’s LGBT collection includes a complete set of issues of Southern Voice, as well as popular national gay magazines, national and local newsletters, academic papers, and literature. It reveals a growing analysis of issues within the lesbian and gay communities, and preserves the emergent media, poetry, and plays that expose and champion the struggles of individuals and the collective community.

Rosemary Magee, director of MARBL, says the collection supports Emory’s deliberate emphasis on research in the liberal arts.

“These materials are becoming a major resource for MARBL’s teaching and research mission. The use of primary evidence is an increasingly significant focus for the university. Our collections provide the opportunity for undergraduates, graduate students, and scholars in all fields to see the connections between their work and the powerful voices represented here,” Magee says.

Lauran Whitworth 16PhD, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, began working in MARBL processing incoming materials for the library’s collections in 2013 and now serves as a graduate curatorial assistant for Gue.

Lauren Whitworth, Emory PhD candidate

As she worked with the materials—particularly LGBT periodicals and feminist and lesbian separatist literature and publications—she began to see a pattern. Many groups and publications used representations of nature in their materials.

With an undergraduate degree in English and art history, Whitworth found the symbolism intriguing, and it has shaped her personal scholarship. She is using materials from the archive, as well as film and art, in her dissertation to “examine the role of representations of nature in LGBTQ liberation movements.”

“A popular symbol in 1970s feminist and lesbian thought is a web like a spider’s web. To me the archives are a lot like a web—full of connectivity, often unexpected or easily missed; ever evolving or changeable; and messy,” she says. “Like a web, an archival collection still has its holes, but it nonetheless reveals points of connection in the past and, in doing so, spurs further connection in the present.”

MARBL opened its first exhibition of materials in the LGBT collection—“Building a Movement in the Southeast: LGBT Collections in MARBL”—in August 2013.

Wandering the exhibit, David McClurkin 74C recognized items that were very similar to those he and his husband, Ken Hunt, had collected during thirty years together. He encouraged Hunt, a longtime public health adviser at the CDC, to donate his professional papers, as well as items from the couple’s shared history in gay rights and human rights activism, community organizing, and HIV/AIDS work throughout the Southeast.

Hunt has an extensive history in the public health field, stretching back to the early days of HIV/AIDS. But just as important are the personal mementos that shaped him along the way.

In the collection he donated to MARBL, Hunt says two books—The Front Runner by Patricia Nell Warren and The Persian Boy by Mary Renault—were significant to him early on.

“When you are trying to think about what your path is, you need to see a person who has gone down your path before you; how they’d done it and where they were in their lives,” Hunt says. “My connection to those books, in part, was me looking for a mentor. They were very impactful. They were important in learning about myself and the community I was growing into and that was helping me grow.”

Adding to that personal history, Hunt and McClurkin traveled to California, where they were married on April 25 of this year in the rotunda of San Francisco’s City Hall.

“It was very important to us to have the right to be married if we chose to. We’ve been, in every sense, married for twenty-nine years,” McClurkin says. “We chose to do it now for a couple of reasons. One is to stand and be counted. The other is to be eligible for the rights and benefits to which married couples are automatically entitled.”

In the year since the US Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to restrict federal interpretation of “marriage” and “spouse” to apply only to heterosexual unions, many same-sex couples—like McClurkin and Hunt—have traveled to the seventeen states where same-sex unions have been legalized in order to marry.

By doing so, they ensured they are entitled to the 1,138 federal rights, benefits, and privileges connected to marital status, including Social Security and veteran’s benefits, federal civilian and military benefits, taxation, and immigration and naturalization benefits.

Just three days before Hunt and McClurkin were married on the opposite coast, Lambda Legal, a national LGBT legal organization, filed a federal lawsuit challenging Georgia’s constitutional ban on same-sex marriages.

Stephen R. Scarborough 87C was a staff attorney in Lambda’s Southern regional office in 1998. He authored the amicus brief that led to the Georgia Supreme Court striking down Georgia’s 182-year-old sodomy law on the grounds that it violated the right to privacy guaranteed by the state’s constitution.

“There is a sense lately that everything is happening so very quickly in the LGBT rights movement. It is tempting to forget that there was a lot of groundwork that was done previously to get to this point,” Scarborough says. “To the extent that the civil rights work in this area can be documented and preserved, it’s important to tell a story that otherwise would be glossed over. Whatever hits us most recently seems to be emphasized, but there were centuries of nonrecognition of our existence, then active hostility to it. There has been a lot of work done, some by lawyers and some by just brave people, to get us to this point.”

After studying public and criminal law at Yale Law School, Scarborough practiced as a federal public defender until returning to Atlanta in 1997 to work with Lambda Legal’s new Southern regional office. Within a year, he had helped overturn Georgia’s sodomy law—a victory that set the stage for future progress.

“As long as they could say ‘this is illegal,’ you could be denied visitation with your children, be fired or denied employment—so many things. If you look at the little amount of time that has passed between decriminalization and now, it is remarkable,” he says.

In March, Emory hosted the Whose Beloved Community? Black Civil and LGBT Rights Conference, sponsored by the university’s James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference and the Center for Women at Emory (CWE). More than three hundred attendees gathered to examine the points of intersection and divergence among the US black civil rights and LGBT movements and to explore ways to advance a comprehensive vision of justice.

Leslie Harris, associate professor of history and African American studies, cochaired the international conference with Dona Yarbrough, associate vice provost for community and diversity and director of the CWE.

Leslie Harris, associate professor of history and African American Studies

“The issues surrounding LGBT rights, racial identity, gender identity, and sexuality hit on different things. But the idea of civil rights is not about just racial equality, it is about defining our rights as human beings,” Harris says.

The complex, and sometimes tense, relationship between the African American and LGBT movements has been challenging for black members of the LGBT community, Harris says—but that is changing.

In 2011 the Arcus Foundation, a global organization dedicated to advancing equality for LGBT people, awarded Emory a grant to examine the historical, political, and cultural connections between the civil rights and black LGBT movements. The late Rudolph Byrd, founder of the Johnson Institute and Goodrich C. White Professor of American Studies at Emory, assembled a working group of international scholars and experts whose work culminated in the Whose Beloved Community Conference.

“Rudolph Byrd began to put a lens on examining this at Emory. Black LGBT people have been obscured in discussions of traditional civil rights and LGBT movements. They have parallel and unique issues that are not taken into account,” Harris says. “Attention needs to be given to the distinctive issues faced by black LGBT individuals.”

Yarbrough adds that many feel there are much more important issues than marriage—economic justice, access to health care for victims of HIV/AIDS, legal justice issues.

“People in the black LGBT community often describe themselves as marginalized in the larger black community and in the larger LGBT community,” Yarbrough says. “That is why this conference was really moving, because we saw people coming together from all over the United States and internationally and finding community there.”

In June, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights opened its new museum and center in Atlanta. CEO Doug Shipman 95C likens the LGBT rights struggle to the “long tail of integration” that still leads to firsts, such as Barack Obama’s 2008 election as the first African American US president. He foresees a similar path for LGBT rights.

“When families come to the exhibit on civil rights history, everyone may have a positive reaction to the exhibit, but when they get to the display on LGBT rights, there are vast differences among the generations,” Shipman says. “That intergenerational conversation around LGBT rights is one of the most important dialogues that can happen, and the center can be helpful in those discussions. Often only time can change a society’s perception of civil rights issues.”

Shipman says it is gratifying to see Emory making LGBT history an institutional priority by investing in the collection in MARBL.

“Human rights is not a destination. We have to work on it and constantly push the boundaries to keep it going,” he says. “Scholarship is a great part of that. Opening and creating a space for people to be able to be who they want to be, especially at a university like Emory, is critical to progress.”

As incoming president of the Emory Alumni Board, Shipman says the LGBT collection complements MARBL’s African American holdings and the strength of the CWE, as well as scholarship in these and related fields.

“Making sure Emory reflects the diversity of its alumni base is a real priority for me, in its leadership, its pipeline, and its programming,” he says. “This is a really good step in that direction because there are many alumni whose history is represented in this collection.”

The Power of Making It Personal

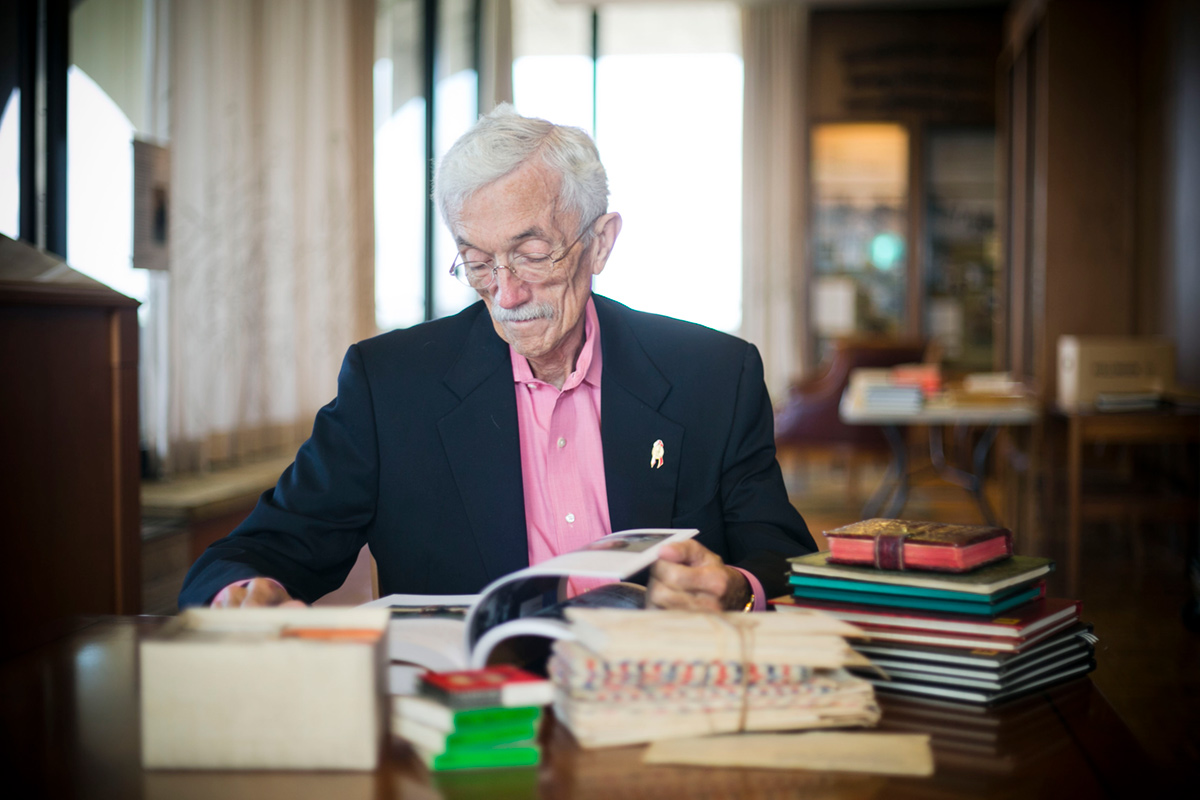

In the early 1980s, Jesse Peel’s Atlanta psychiatric practice focused on the needs of the LGBT community, especially gay men who were consumed by the terror, anger, and grief the AIDS crisis had ignited.

“I was the token gay guy in a large psychiatric group, and about a third of my practice was gay men,” he says. “I began to see young men who were sick, who had friends who were sick, who had fears about their own health. As I began working with these guys, I wanted to get involved more in the community.”

Peel’s appointment calendars are a telling record of how his life changed during the crisis.

The calendar from 1974 is filled with personal appointments and notes—theater and musical events, trips and dinners with friends, parties, birthdays, and church events. By 1984, the pages begin to chronicle biweekly meetings with AID Atlanta and all-too-frequent funerals and memorial services.

On the last page of the 1986 calendar is a list of names and dates—the friends and acquaintances who succumbed that year to AIDS-related illnesses or to the despair of the disease. Peel kept a tally in each year’s calendar until 1992, when the total reached seventy-three. After that he stopped counting, but the lists, with dates and personal notes, kept going.

Determined to do something, he attended a health conference at Emory where he met the director of AID Atlanta and offered to help. Because so many others did the same, Atlanta became a model of how an urban community can respond to a crisis of such proportions, Peel says.

“Atlanta had been a leader in the civil rights movement, and that was a blueprint for us on how to get things done for the common good. We had an awful lot of support from [then–Atlanta Mayor] Andy Young and people at the [Georgia] Department of Human Resources who understood that this was a major health care crisis. We also had a lot of friends in the straight community that we could not have done this without,” he says. “We had the CDC doing the scientific work, we had ACT UP doing the activism part in the street, we needed people who were going to create the policies and create change.”

In addition to his work with AID Atlanta, Peel served on the state AIDS Task Force and on the boards of many organizations that sprang from programs AID Atlanta started.

After retiring in 1992, he often wondered what would become of the extensive documentation he had collected of his lifetime.

“Emory offers us a place where this history will be preserved and respected, where they are bringing in other collections that relate to them and create a more complete picture. Looking at MARBL’s collections in civil rights and health, AIDS fits right in the middle of that,” Peel says. “I am not sure how this will be used in the future, but I know our community is part of the Atlanta story and our stories need to be preserved. So many of our peers are already gone and whatever history they had, important or not, is gone.”