Poetic Memory

Kevin Young still remembers the smell of the mimeographed poem the instructor circulated among his fellow seventh graders. The teacher of this summer writing workshop intentionally omitted the name of the poet, wanting his gifted middle school students to focus on the words rather than the writer. But the thirteen-year-old Young instantly recognized the poem. It was his.

“Kevin stood out to me pretty darn early,” says Thomas Fox Averill, writer in residence and professor of English at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas, who led that workshop.

“Kevin had a real love of and facility with language that was pretty extraordinary for his age,” he says, recalling Young’s first attempts at writing poetry.

The son of an ophthalmologist father and chemist mother, Young fell in love with the world of poetry that summer.

“The secret thrill of seeing my poem being passed around was enough to get me writing, and reading, lots of poetry,” he says.

Flash forward thirty years.

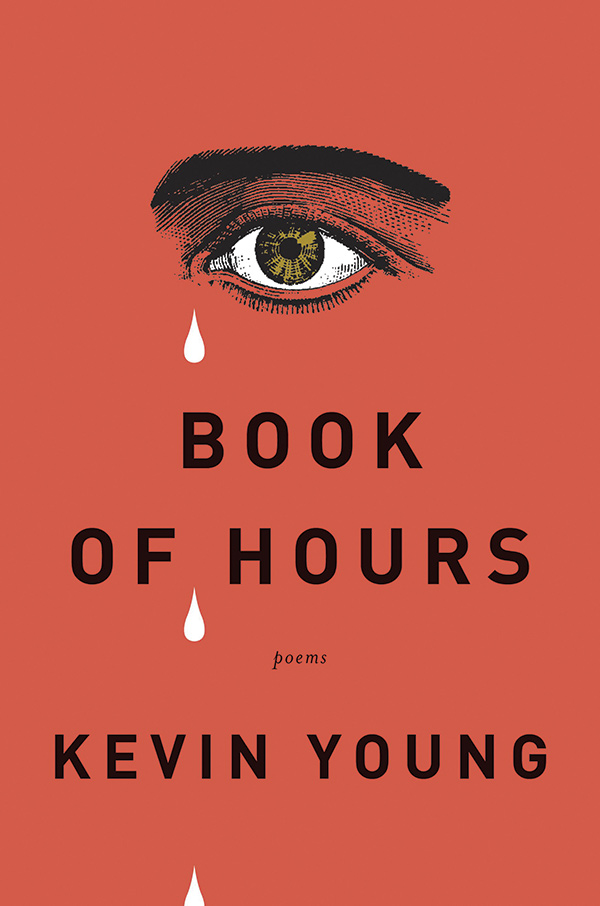

Now the Atticus Haygood Professor of Creative Writing and English, an endowed faculty position that is among Emory’s highest honors, Young returned to Topeka in April for a reading from Book of Hours, his widely praised eighth collection of poetry released by Knopf a month earlier.

In the midst of a national tour to promote his latest book, the trip home included a two-day stint as author in residence at his alma mater, Topeka West High School.

“It was intense,” Young says. “I was teaching in the very room where I sat and learned from visiting writers.”

That experience, however, was not the only reason Young described the visit as intense. Ten years earlier, Young returned to Topeka in the wake of his father’s untimely death—the result of a hunting accident. While grieving the loss, Young had to deal with the heartbreaking responsibilities—some significant, others small—left to loved ones: deciding which organs to donate; finding homes for his father’s dogs; giving away his clothes.

These are the moments that form the first part of Book of Hours—less elegy for his father, more daybook of grief that explores the “daily process of living after his death.”

In the poem “Charity,” Young shares the difficult task of picking up his father’s dry cleaning:

one place with none

of your clothes,

just stares as if no oneever dies, as if you

are naked somewhere,

& I suppose you are.Nothing here.

The last place knows exactly

what I mean, brings me shirtshanging like a head.

Starched collars

your beard had worn.One man saying sorry, older lady

in the back saying how funny

you were, how you jokedwith her weekly. Sorry—

& a fellow black man hands

your clothes back for free,don’t worry. I’ve learned death<

has few kindnesses left.

Such is charity—so rare& so rarely free—

that on the way back

to your emptying houseI weep. Then drive

everything, swaying,

straight to Goodwill—open late—to live on

another body

& day.-From "Charity", 2013

For Averill, who spent time with the poet in Topeka during the days after the tragedy, reading Book of Hours causes a flood of memories.

“His ability to know what to say and how to say it is the real strength of the book,” Averill says. “You didn’t have to be there to understand and relate to these poems.”

Young, who revisits his father’s death and his own grief with every reading and interview for Book of Hours, says it can be difficult at times.

“But these poems are comforting,” he says. “Poems transform the memory, and they can change the reader’s own experience of grief.

“We often don’t talk about grief and loss in our culture,” Young adds. “Poems are a powerful way to do that.”

Not all of Book of Hours, however, confronts death and loss. Young moves to another point in the cycle of life in the second section of the book, writing about the birth of his son in poems like “Colostrum”:

We are not born

with tears. Yourfirst dozen cries

are dry.It takes some time

for the world to arriveand salt the eyes.

Young concludes Book of Hours with a section of poems about his own rebirth following the death of his father and arrival of his son.

After publishing his first book of poetry at the age of twenty-four, Young has managed to merge marathon and sprint, writing seven more full-length collections of poetry, editing eight anthologies, and penning a nonfiction book that put him on the map as a cultural critic.

His award-winning oeuvre as a poet is as diverse—in subject matter, themes, and form—as he is prolific: Jean-Michel Basquiat, the blues, his family roots in Louisiana, elegies, rebellion on the Amistad, odes to food, film noir, and grief.

“Kevin is a remarkable poet,” says Natasha Trethewey, Robert W. Woodruff Professor of English and Creative Writing at Emory who served two terms as the nineteenth US Poet Laureate (2012–2014). “His knowledge of poetry, history, and popular culture informs his work as a scholar and teacher—from the Atlantic slave trade to the blues to the elegy.”

Amy Hildreth Chen 10G 13PhD included Young on the syllabus for a course she taught at Emory for first-year English students in 2010, From Birmingham to Belfast: Reading American and Irish Civil Rights Poetry. Instructors at other universities are doing likewise.

“His work is very accessible to a new poetry audience, yet he still tackles important subject matter,” she says. “Kevin brings a poignant perspective that doesn’t let you off the hook, but he has a tone and style that allow students to really connect with the poems.”

Young and students during a recent class.

Young earned his undergraduate degree from Harvard University, followed by a Stegner Fellowship in Poetry at Stanford University and an MFA in creative writing from Brown University. The beneficiary of renowned teachers and mentors, including Nobel Prize in Literature recipient Seamus Heaney, Young knows firsthand the power of passionate professors.

“I learned from them each in different ways,” he says. “Most importantly, I learned how to be a writer in the world, that it’s possible to be a writer for the long haul, through daily effort and experience.”

That is exactly what Young is imparting to the next generation of writers and poets.

“He is very approachable and always encouraging,” says Esther Lee, a former graduate student of Young who is now an award-winning poet and assistant professor of English and creative writing at Agnes Scott College.

“We learned how to be artists with integrity and move through the world with grace,” Lee says, citing Young as a principal force in her evolution as a poet. “We were allowed to experiment and fail, with some successes mixed in.”

As contemporary and colleague, Trethewey knows just what Emory has in Young.

“Kevin Young is a major voice in American poetry,” she says, “not only because of the quality of his fine poems but also because of his work as an editor, critic, and curator.

“Students at Emory have the unique opportunity to work with him in poetry writing workshops as well as in courses devoted to using the archives and curating exhibits featuring the poets included in our vast holdings,” Trethewey says.

Young, who joined Emory in 2005, urges his students to focus on process rather than end result.

“I really try to get them to think of the poetry workshop as a laboratory—try things, fail better, forward progress,” he says, echoing Samuel Beckett’s oft-quoted words:

Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter.

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

As curator of Emory’s Literary Collections and the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library—the world-renowned, seventy-five-thousand-volume collection of rare books, first editions, manuscripts, and more—Young enjoys the ability to show, not just tell, his students why investing in the “pleasure of process” is essential.

'[Kevin] has incredible discernment and a collector's eye, which infuses all aspects of his work.' —Raymond Danowski, shown here with former Emory President William Chace and Kevin Young on a recent tour of the Danowski Poetry Collection at Emory's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library.

“The archive is a great place to see that,” he says, adding that the many drafts, marked-up manuscripts, and iterations of well-known works reveal how writers pursue perfection.

From limited editions by Langston Hughes with corrections in his own hand to drafts by Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, W. B. Yeats, Beckett, and Heaney, the remarkable materials in the collection “show us the poet at work, through drafts, revisions, cross outs,” Young says, resulting in an understanding of the creative process that can’t be gleaned from the published volumes at the bookstore.

“I’ve always thought of the Danowski Poetry Library as a living library,” says Young, who has served as its only curator. “It tells us a lot about the twentieth century and even some of the twenty-first. Poetry, broadly defined, does that better than anything else.”

During a rare visit from the collection’s namesake in June 2014, Young led Raymond Danowski on a tour of the stacks. They first stopped for a look at the expansive treasury of first editions, manuscripts, proofs, and other materials from Black Sparrow Press, the independent publishing company that rolled the dice on Charles Bukowski when no others would. As Young highlighted, the comprehensive collection—second only to that of the company’s founder, John Martin—now even includes an original letterpress block with the publisher’s logo.

“He has incredible discernment and a collector’s eye, which infuses all aspects of his work,” Danowski says. “Not only is he one of the best English-language poets today, Kevin has invigorated the library with his energy and lifted it to a vital level.”

Though Young’s list of favorites in the collection can fill a book, he points to a first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass as the cornerstone. Another rare gem, he said, is a “true first edition” of Allen Ginsberg’s seminal Howl—one of about twenty-five known copies typed and mimeographed by the poet to send to peers, prior to its publication by City Lights.

Chen, now a postdoctoral fellow with a focus on special collections at the University of Alabama, credits her success to serving as Young’s graduate research assistant for three years.

“By spending so much time with Kevin, I learned a whole profession,” Chen says. “He taught me a lot about curating and the rare book trade. He also taught me so much about literature just from looking at the manuscripts and rare books in the archive. There are not many people working in special collections who are also working poets.”

Young’s love for books seeps into his poetry workshops, too. After inviting printers to speak to his class, Young tasked his students with creating chapbooks of their work last semester.

“Doing that is so radically different than just handing in a portfolio at the end of the semester,” he says. “They had to organize their poems with more thought, not just in chronological order. What they submitted was so inventive, it makes me want to do more of that.”

For Young, a self-described autodidact, learning is a perpetual process, and the roles and responsibilities of poet, professor, and curator are intertwined—his years of experience as a writer shared with students who, in turn, stoke his creative fire through their efforts; his own work informed by revelations uncovered in the archive, which offer students portals into the process of the literary heroes they admire.

“They all feed into each other,” he says.

But when Young made the decision at Harvard to pursue his love of poetry as a career, his mother, public health professional Azzie Young, worried how he would feed himself. She called her son’s first mentor, Tom Averill.

“We had some initial concerns,” she says, “so we sought information from one of the best writers we knew at the time.”

Averill’s advice: “Whatever Kevin decides to do, it’s going to work out well.”

By all accounts, Young proved his mentor right.

“Not everyone lives up to their potential,” Averill says. “Kevin has."