Evolving Empathy

Coda

Asked by a religious magazine what I would change about the human species “if I were God,” I had to think hard. Every biologist knows the law of unintended consequences, a close cousin of Murphy’s Law. Anytime we fiddle with an ecosystem by introducing new species, we create a mess. Whether it is the introduction of the Nile perch to Lake Victoria, the rabbit to Australia, or kudzu to the southern United States, I am not sure we’ve ever brought improvement.

Each organism, including our own species, is a complex system in and of itself, so why would it be any easier to avoid unintended consequences? In his utopian novel Walden Two, B. F. Skinner thought humans could achieve greater happiness and productivity if parents stopped spending extra time with their children and people refrained from thanking one another. They were allowed to feel indebted to their community, but not to one another. Skinner proposed other peculiar codes of conduct, but those two specifically struck me as blows to the pillars of any society: family ties and reciprocity. Skinner must have thought he could improve on human nature. Along similar lines, I once heard a psychologist seriously propose that we should train children to hug one another several times a day, because isn’t hugging by all accounts a positive behavior that fosters good relations? It is, but who says that hugs performed on command work the same? Don’t we risk turning a perfectly meaningful gesture into one that we can’t trust anymore?

We have seen in Romanian orphanages what happens when children are subjected to the baby-factory ideas of behaviorist psychology. I remain deeply suspicious of any “restructuring” of human nature even though the idea has enjoyed great appeal over the ages. In 1922, Leon Trotsky described the project of a glorious New Man:

There is no doubt whatever but that the man of the future, the citizen of the commune, will be an exceedingly interesting and attractive creature, and that his psychology will be very different from ours.

Marxism foundered on the illusion of a culturally engineered human. It assumed that we are born as a tabula rasa, a blank slate, to be filled in by conditioning, education, brainwashing, or whatever we call it, so that we’re ready to build a wonderfully cooperative society. Have you ever noticed how the worst part of someone’s personality is often also the best? You may know an anally retentive, detail-oriented accountant who never cracks a joke, nor understands any, but this is in fact what makes him the perfect accountant. Or you may have a flamboyant aunt who constantly embarrasses everyone with her big mouth, yet is the life of every party. The same duality applies to our species. We certainly don’t like our aggressiveness—at least on most days—but would it be such a great idea to create a society without it? Wouldn’t we all be as meek as lambs? Our sports teams wouldn’t care about winning or losing, entrepreneurs would be impossible to find, and pop stars would sing only boring lullabies. I’m not saying that aggressiveness is good, but it enters into everything we do, not just murder and mayhem. Removing human aggression is thus something to consider with care.

Humans are bipolar apes. We have something of the gentle, sexy bonobo, which we may like to emulate, but not too much; otherwise the world might turn into one giant hippie fest of flower power and free love. Happy we might be, but productive perhaps not. And our species also has something of the brutal, domineering chimpanzee, a side we may wish to suppress, but not completely, because how else would we conquer new frontiers and defend our borders? One could argue that there would be no problem if all of humanity turned peaceful at the same time, but no population is stable unless it’s immune to invasions by mutants. I’d still worry about that one lunatic who gathers an army and exploits the soft spots of the rest.

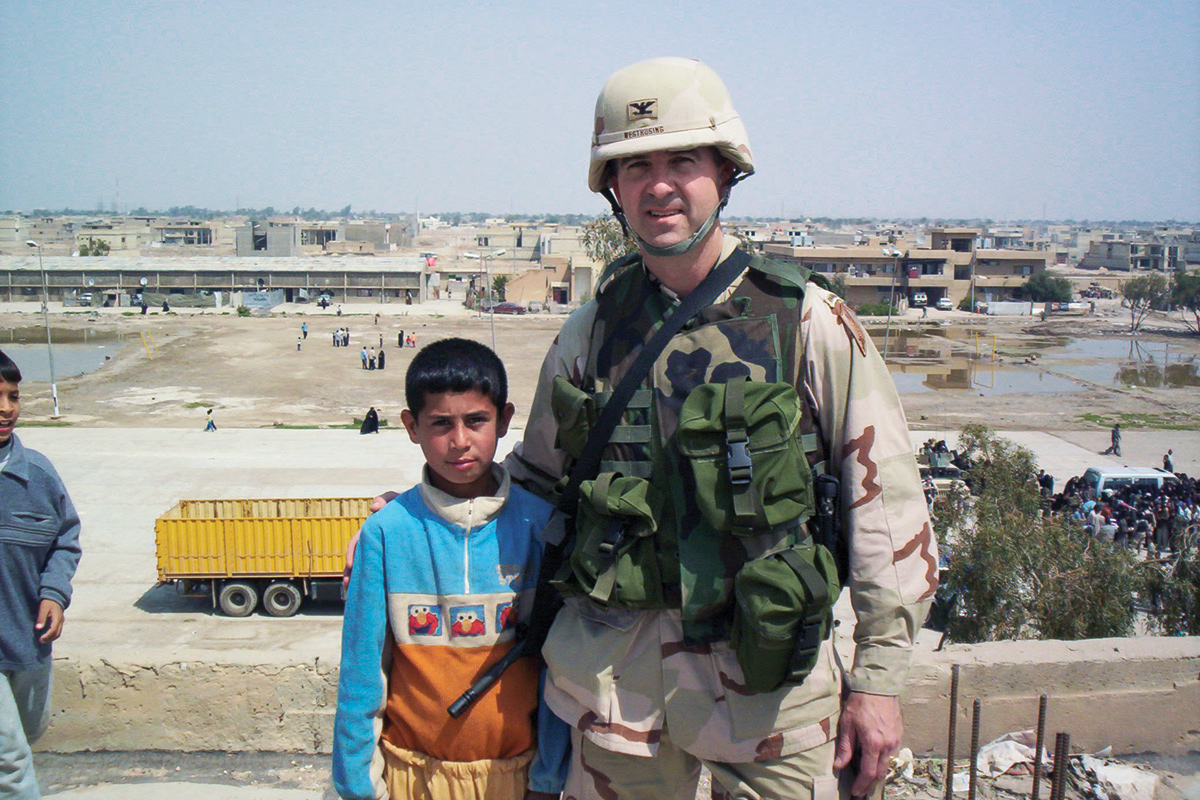

So, strange as it may sound, I’d be reluctant to radically change the human condition. But if I could change one thing, it would be to expand the range of fellow feeling. The greatest problem today, with so many different groups rubbing shoulders on a crowded planet, is excessive loyalty to one’s own nation, group, or religion. Humans are capable of deep disdain for anyone who looks different or thinks another way, even between neighboring groups with almost identical DNA, such as the Israelis and Palestinians. Nations think they are superior to their neighbors, and religions think they own the truth. When push comes to shove, they are ready to thwart or even eliminate one another. In recent years, we have seen two huge office towers brought down by airplanes deliberately flown into them as well as massive bombing raids on the capital of a nation, and on both occasions the deaths of thousands of innocents was celebrated as a triumph of good over evil. The lives of strangers are often considered worthless. Asked why he never talked about the number of civilians killed in the Iraq War, US defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld answered: “Well, we don’t do body counts on other people.”

Empathy for “other people” is the one commodity the world is lacking more than oil. It would be great if we could create at least a modicum of it. How this might change things was hinted at when, in 2004, Israeli justice minister Yosef Lapid was touched by images of a Palestinian woman on the evening news. “When I saw a picture on the TV of an old woman on all fours in the ruins of her home looking under some floor tiles for her medicines, I did think, ‘What would I say if it were my grandmother?’ ” Even though Lapid’s sentiments infuriated the nation’s hard-liners, the incident showed what happens when empathy expands. In a brief moment of humanity, the minister had drawn Palestinians into his circle of concern.

If I were God, I’d work on the reach of empathy.

This excerpt is from Frans de Waal's latest book, The Age of Empathy (Crown Publishers, 2009), from a chapter originally titled "Crooked Timber." De Waal is Charles Howard Candler Professor of Primate Behavior in Emory's Department of Psychology and director of the Living Links Center at Yerkes National Primate Research Center.

Email the Editor