Mistress of Mischief

Margaret Atwood's other worlds

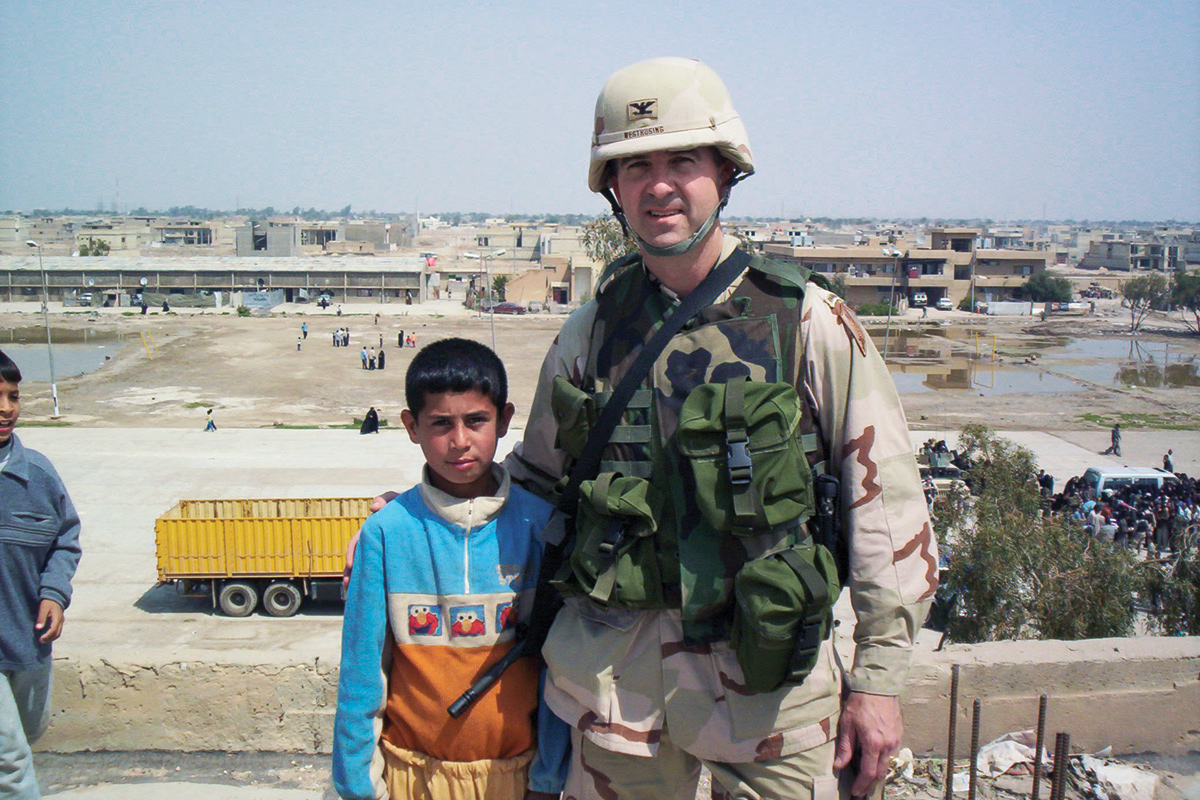

Giving Plause: Atwood describes her work as speculative fiction rather than sci-fi.

Ann Borden

Fans of the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature—now among the preeminent lecture series in North America—have come to expect major literary lights and stimulating thought. But joie de vivre?

The series director, associate professor Joseph Skibell, uttered that promise—dressed up in French, no less—in his opening-night introduction of Margaret Atwood. Beyond the series’ high intellectual content, he said, it “has involved . . . chamber music, mariachi bands, margarita fountains, barbecues, fiddle contests, and Nobel Prize-winning poets declaiming their verse. The series is a celebration not just of literature but of life.”

At seventy-one, though, would Atwood continue the tradition as vigorously? The short answer is: never count out a woman raised without modern conveniences in the north woods of Canada whose mother was an ice dancer until the age of seventy-five. The longer answer follows.

Atwood proclaimed at the opening of the first lecture in the series—titled “In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination”—“I have spent quite a lot of my life writing fiction and poetry and some other things, but this has not made me a professional scholar or expert on any subject, including the ones I am about to discuss.”

Atwood, though, is every bit the expert that she swears she is not, especially in talking about SF. The term variously has been used to mean science fiction, speculative fiction, and sword and sorcery fantasy.

A literary skirmish broke out in 2009 when longtime science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin 88H wrote in the Guardian: “Margaret Atwood doesn’t want any of her books to be called science fiction. . . . [S]he says that everything that happens in her novels is possible and may even have already happened, so they can’t be science fiction. . . . This arbitrarily restrictive definition seems designed to protect her novels from being relegated to a genre still shunned by hidebound readers, reviewers, and prize-awarders.”

Tough talk, and it has compelled Atwood to be deliberate about what science fiction is and isn’t and where her own books fall along these fuzzy divides. An intellectual battle clearly has been joined from which neither side will retreat. As Atwood explains her position, “What I mean by science fiction is those books that descend from H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, which treats of an invasion by Martians—things that could not possibly happen. Whereas, for me, speculative fiction means things that descend from Jules Verne’s books about submarines and such—things that really could happen. . . . I would place my own books in this second category.” It is not that she doesn’t like Martians, she protested. “They just don’t fall in my skill set.”

She spoke charmingly of the early influences—Dell mysteries, Sherlock Holmes, Treasure Island, Grimm’s Fairy Tales—on her and her elder brother. They were highly creative kids, fighting over colored pencils to depict their flying rabbits. Her brother’s rabbits lived on the planet Bunny Land, where they battled evil foxes, robots and man-eating plants, and lethal animals. Atwood’s rabbits “inhabited a more mysterious place called Mischief Land.” Arguably, the author has never left there.

Child's Play: Atwood described—and displayed—the rich imaginary worlds she and her brother created as children, including Bunny Land and Mischief Land.

Ann Borden

Lecture two, “Burning Bushes,” delved into her years at the University of Toronto studying with Northrop Frye. She eventually learned “where angels, devils, and talking vegetation went after the age of John Milton and Paradise Lost.” Their exodus was to the other worlds of science fiction, which Atwood believes often has been used to act out theological doctrine. Why this migration from Earth to, in Atwood’s construct, Planet X? “We no longer believe in the old religious furniture. . . . On Planet X, [gods and devils] can take part in a plausible story—and we still want to follow them there because, like it or not, our own deep inner lives still contain them.”

In “Dire Cartographies,” the final lecture, the subject was ustopia, a word Atwood created from utopia and dystopia. As one might imagine, Atwood is more interested in the complex intersection of utopia and dystopia than either genre proper. “Scratch the surface a little,” she says. “Within each utopia is a dystopia, and the reverse.” She talked at length about the first of her three ustopias, The Handmaid’s Tale. Treated as a “yarn” in the UK, in this country critic Mary McCarthy said the novel lacked imagination and couldn’t happen here. And yet, someone wrote on the Venice Beach sea wall, “The Handmaid’s Tale is already here.”

The mood soon lifted, though, and here’s the promised final tally on the joie de vivre in this year’s lectures. While here, Atwood galloped from one thing to the next, those loose grey curls darting to and fro, like her quick wit. In between the demanding lectures, she fit in a Creativity Conversation, an appearance in an English class (she is, indeed, a “major author”), tweeted, told jokes (what is the difference between capitalist hell and socialist hell?), spoke in parables (the fox and the cat), and belted out one of the God’s Gardener’s hymns from The Year of the Flood with Joseph Skibell. It doesn’t get more joyous than that—at twenty-one or seventy-one.

Vice President and Secretary Rosemary Magee, who was the other half of the Creativity Conversation, noted: “Atwood’s literary genius spans multiple generations and provokes deep thinking about who we are as human beings and who we want to be. Drawing hundreds of people to her lectures and reading, she was profound and prophetic.” To which, one more “p” word seems appropriate: peppy.