Prelude

The Choices We Make

When I was about fourteen—the age my son is now—I stole a pair of bowling shoes.

It was a snap, really. Some friends and I had gone bowling on a rainy afternoon, out of small-town boredom, I suppose. Rather than changing back into my own shoes after we finished, I walked out in the bowling shoes. I thought they were cool. I thought I was cool.

I also thought that taking them was not such a big deal. I had left my own tennis shoes, after all, which were actually much nicer. So I didn’t even bother to try to hide them from my parents. Which was a mistake.

My father was livid. He roared. He made me take the shoes back, find the bowling alley manager, and apologize (the mystified man kindly returned my own shoes). I truly believe my dad thought jail time would not have been too harsh a lesson.

At the time, I thought his reaction was overkill. But now that I’m a parent myself, I understand that it wasn’t just about some worn-out bowling shoes. It was about his need to see his own high standards and deep values reflected in me, and his keen sense of frustration and failure when that reflection blurred. To me, taking the shoes seemed harmless enough—more mischievous than malicious. To him, it was stealing, plain and simple. And if I was capable of that, what other bad things might I do?

Everyone wants to be a “good person,” and most of us, I would bet, think of ourselves that way. We’re so confident that we relish hypothetical scenarios in which our personal ethics are put to the test, as in those TV shows where ordinary citizens are lured into moral predicaments while hidden cameras roll: What would you do if you found a wallet full of cash? Saw a woman being harassed on the street? Suspected your neighbors of child abuse? Would you step in and do the “right” thing? Of course.

But the right thing isn’t always clear, and it can mean different things to different people. Take that last example, in which you’re concerned for a neighbor child’s safety. For some, the most ethical course might be speaking directly to the parents, or reaching out to the child; for others, making an anonymous phone call to the authorities; for someone else, the right path would be minding their own business rather than meddling in others’ personal affairs. The alluring question, “What would you do?” makes for lively dinner conversation, but gets trickier when it’s asked in real life.

In this issue of Emory Magazine, we ask a few questions of our own, starting with the meaning and impact of ethical engagement in the University’s vision statement. Can ethical behavior be taught to college students, or is it deeply embedded in character formation that begins at home many years before? The answer, it appears, may be a little of both; what our faculty can do is urge students to question, to think deeply, to assess and actively respond to problems, and to consider the lives of others different from their own. What is also clear is that Emory hopes to see its stated institutional commitment to ethics reflected in its students, as in all of us who make up the broader community.

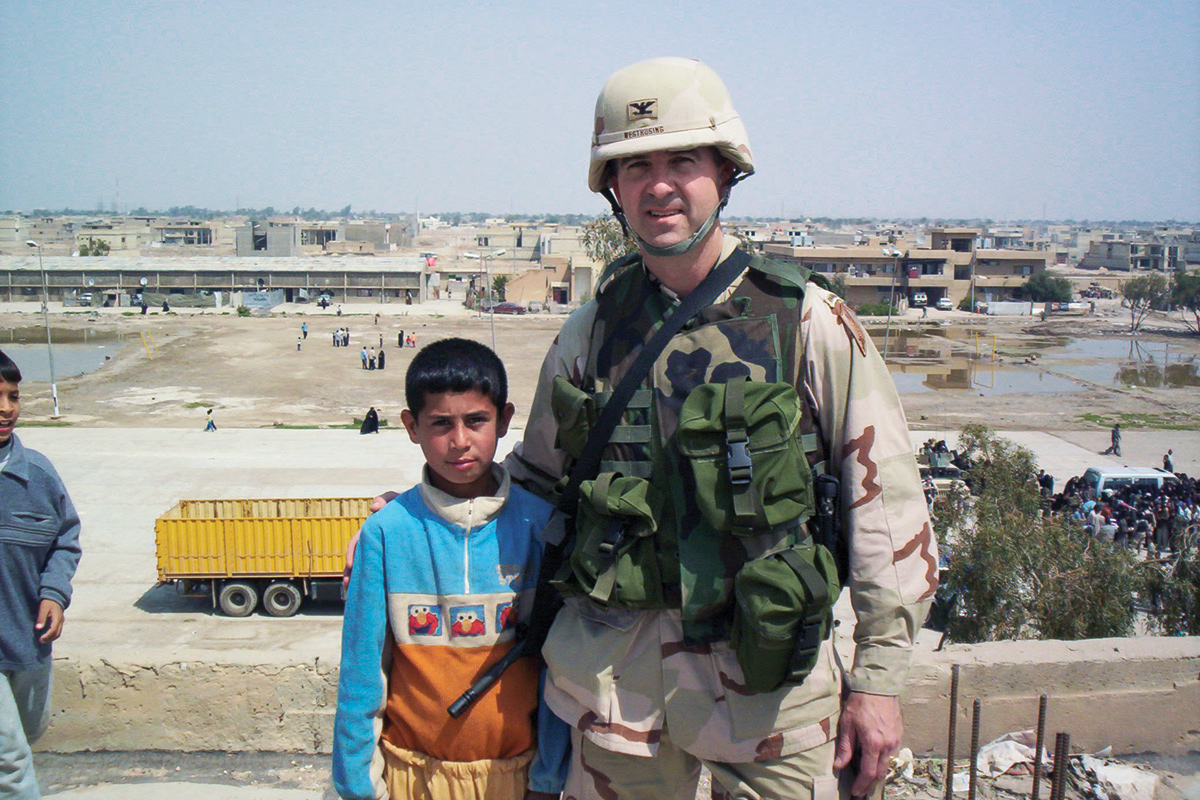

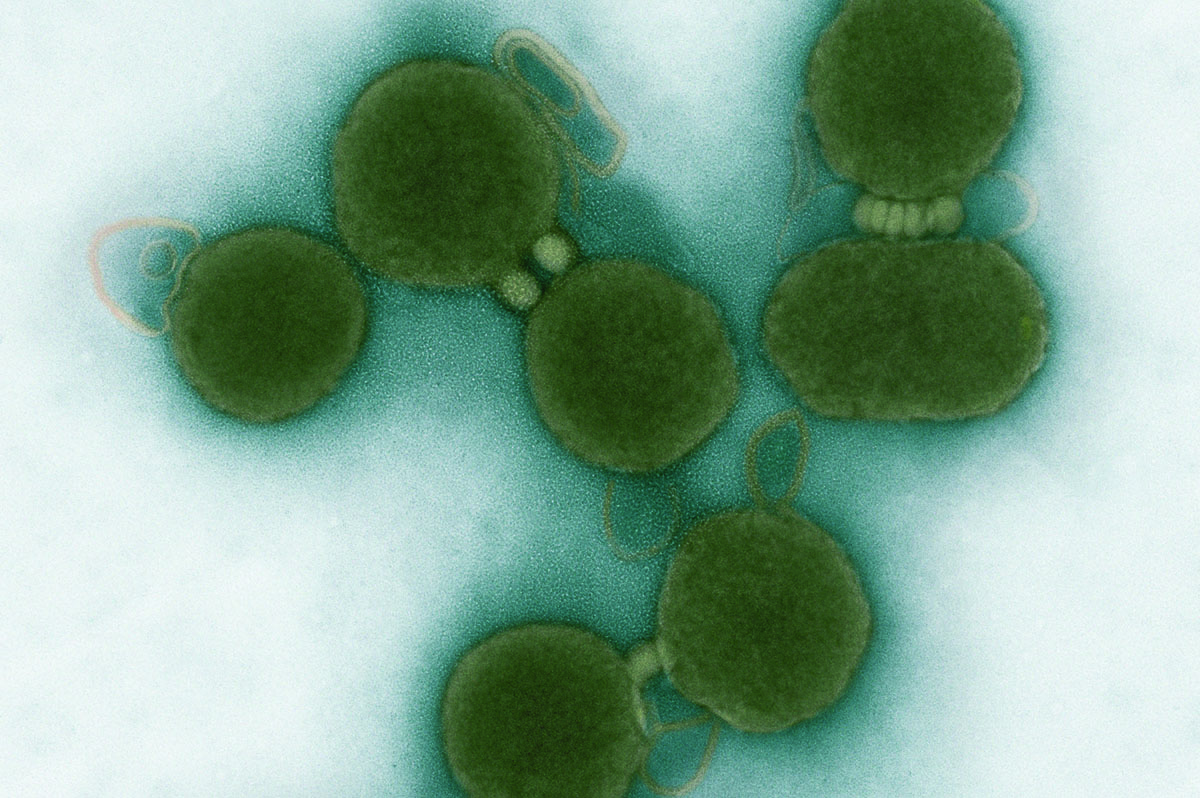

The challenges are steeper for some than others. As vice chair of President Obama’s special Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues, Emory’s own president is confronting some of the thorniest and most compelling ethical problems of the day in the field of synthetic biology—including the fascinating question of whether life can, or should, be created through technology. In this issue, we also visit the widow of Emory graduate Colonel Ted Westhusing 03PhD, who was ultimately unable to reconcile his idea of a “just war” with the work he did in Iraq.

And, as virtual reality becomes the new reality, we asked some faculty experts to weigh in on how people behave online—where sometimes consequences far outstrip intentions.

Most of us don’t have to make recommendations to the White House on bioethics policy, or question whether our contribution to the US presence in Iraq aligns with our studied beliefs regarding war and ethics. But we do make choices every day that shape who we are, as well as who others perceive us to be. Would you keep some extra change given by mistake? Fire off an insult on an Internet forum under a screen name? Spread a juicy rumor about a friend? Pretend to be sick so you can stay home from work? Choose not to help a stranger in trouble? Steal an old pair of bowling shoes?

Are you a good person? Am I?

Honestly, I don’t know. I can only say for sure that I’m glad my dad made me return those shoes. A harmless enough prank, probably; but given the choice, I’d make my son do the same thing.