Brain Trumps Hand in Stone-Age Study

What ancient tools can tell us

Carol Clark

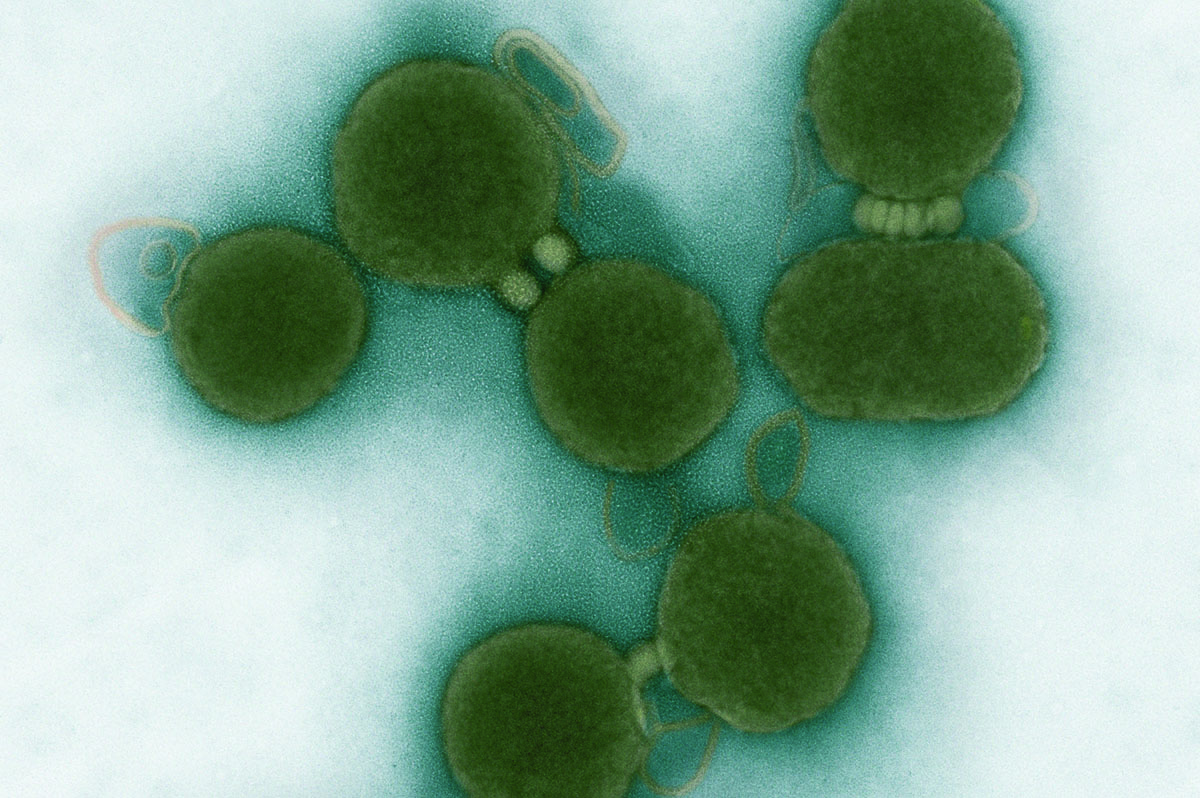

Was it the evolution of the hand, or of the brain, that enabled prehistoric toolmakers to make the leap from simple flakes of rock to a sophisticated hand axe?

A new study finds that the ability to plan complex tasks was key. The research, published in the Public Library of Science journal PLoS ONE, is the first to use a cyber data glove to measure the hand movements of stone tool making precisely and compare the results to brain activation.

“Making a hand axe appears to require higher-order cognition in a part of the brain commonly known as Broca’s area,” says Emory anthropologist Dietrich Stout, coauthor of the study. It’s an area associated with hierarchical planning and language processing, he noted, further suggesting links between tool making and language evolution.

“The leap from stone flakes to intentionally shaped hand axes has been seen as a watershed in human prehistory, providing our first evidence for the imposition of preconceived, human designs on the natural world,” he says.

Stout is an experimental archeologist who recreates prehistoric tool making to study the evolution of the human brain and mind. Subjects actually knap tools from stone as activity in their brains is recorded.

“Changes in the hand and grip were probably what made it possible to make the first stone tools,” Stout says. “Increasingly, we’re finding that the earliest tools required visual and motor skills, but were conceptually simple.”