Mind Over Matters

Studies show that for children and adults, a calm mind can help lead to a healthy body

Finding the Quiet: Even among children, the practice of thinking kindly about others can help bring about more positive emotions and interactions.

iStockphoto

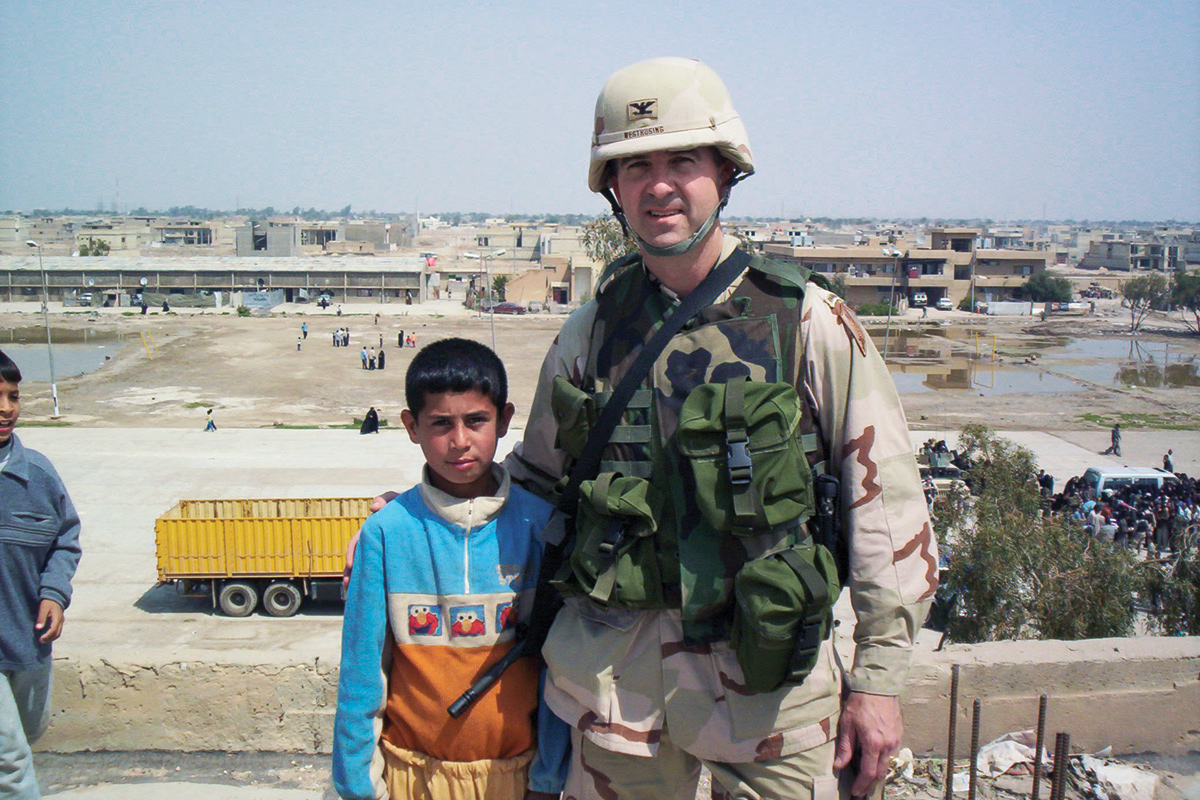

When Brendan Ozawa-de Silva first walked into the classroom of five- to eight-year-olds at Atlanta’s Paideia School, he quickly despaired of ever achieving his objective: getting the children to meditate.

Noisy and excitable, the kids could barely sit still, much less approach the state of utter calm and concentration that is central to the Buddhist tradition. But Ozawa-de Silva captured their attention by speaking an ancient language that every child on earth can understand: a story.

He told them about the sweater he was wearing, describing how his father gave it to him and explaining that it makes him happy because it is warm and makes him think of his father. Then he asked the children to consider the other reasons why he is able to enjoy the sweater—where it came from, who made it, and how it traveled to him. The kids rattled off answers like popcorn on a hot stove: wool, sheep, trucks, roads, stores, people.

“Finally, they shouted out, ‘It never ends. You need the whole world!’, ” Ozawa-de Silva, an Emory PhD candidate, told His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama in his research presentation during the Dalai Lama’s visit to the University in October.

Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi

Emory Photo Video

And just like that, the children understood—at least for a moment—the Buddhist concept of universal interconnectedness that undergirds compassion meditation.

The pilot program at Paideia, which Ozawa-de Silva codirected with graduate student Brooke Dodson-Lavelle, is part of an ongoing series of Emory research initiatives studying the effects of meditation on physical and mental health. The protocol for the program was developed by Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi, director of the Emory-Tibet Partnership and codirector of the Emory Collaborative for Contemplative Studies, using Cognitively Based Compassion Training—a technique drawn from Buddhism, but without the spiritual elements. Secular compassion meditation is based on a thousand-year-old Tibetan Buddhist practice called lojong, which uses a cognitive, analytic approach to challenge a person’s unexamined thoughts and emotions toward other people.

The practice is designed to help participants recognize the interdependence of all creatures and cultivate compassion towards others, whether family, friends, or far-flung strangers. The comprehension of shared suffering is thought to reduce negative emotions, like anger and resentment, and help nurture positive ones, like kindness and gratitude.

Charles Raison

Jack Kearse

“I really think it helps the kids to center,” says Jonathan Petrash, who coteaches a class of five- to seven-year-olds at Paideia. “We have tried to make it part of our daily routine. There is a real calm, settled feeling in our classroom, with deeper and richer conversations. The kids are better able to show empathy, better able to show compassion.”

Ozawa-de Silva was just one of a series of researchers who described their work and findings to the Dalai Lama during his three-day visit, which featured a number of high-profile public events, including a panel discussion on creativity among His Holiness, Pulitzer Prize&8211;winning author Alice Walker, and film star and Buddhist advocate Richard Gere.

During the daylong conference on compassion meditation where Ozawa-de Silva spoke about the Paideia pilot, Charles Raison, associate professor in Emory’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and clinical director of Emory’s Mind-Body Program, presented findings from another study involving youth in Atlanta’s foster-care system.

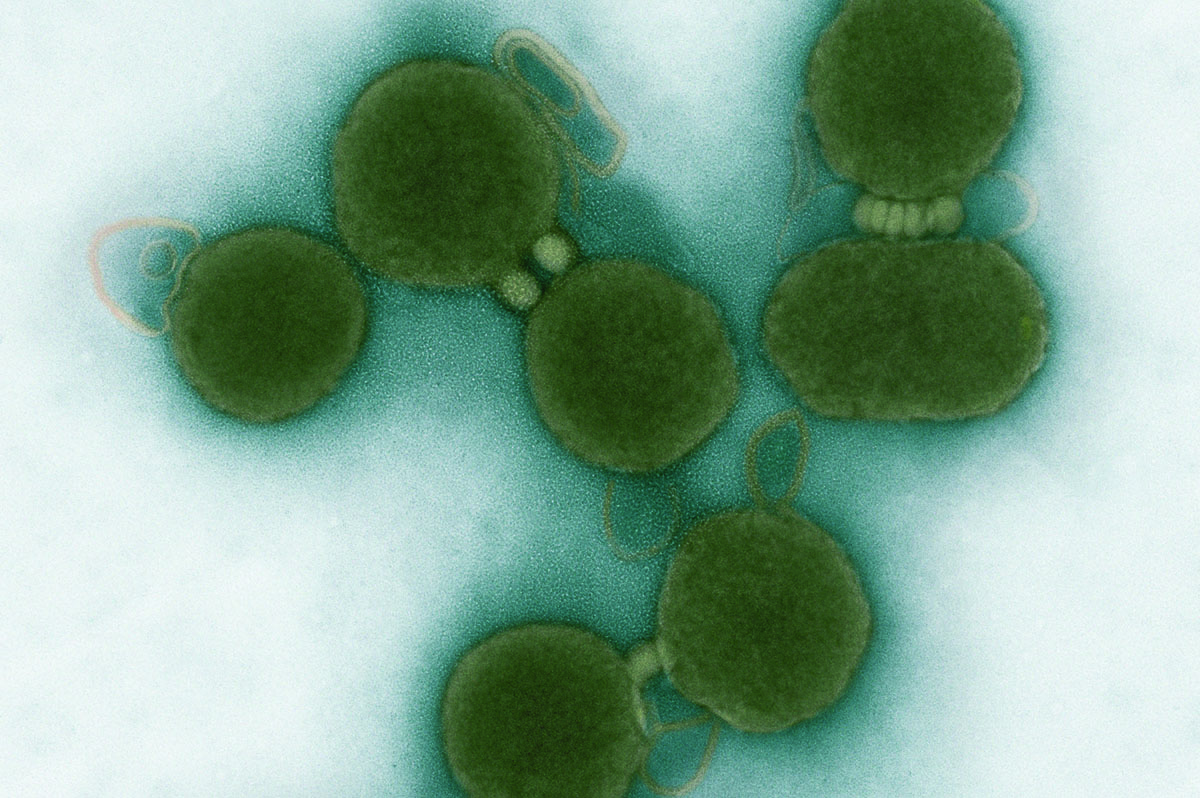

“We know that children who are maltreated experience devastating consequences, such as abnormal levels of stress hormones and inflammation,” Rasion says. “Psychosocial stress is also a risk factor for depression and anxiety.”

Raison and Negi led a 2005 study of college students that indicated that meditation can help reduce stress levels and physical responses like inflammation. Applying the same principles, his team did a baseline assessment of seventy-two children, ages thirteen to seventeen, in the foster-care system, asking a series of questions and testing their saliva for stress hormones. Afterward, half received training in compassion meditation for six weeks.

When they were tested again, Raison says, the results were mixed: there was virtually no difference in their self-reporting, but their stress hormones and inflammation markers were shown to be lower. “There seem to be measurable benefits to our biological systems from compassion meditation,” Raison says.

In a previous clinical intervention, six teenage girls in a foster home were trained in a six-week compassion meditation program aimed at helping them cultivate inner strength, self-esteem, and hope. They did report benefits from meditation, including improved interaction with others; one girl told Dodson-Lavelle that the training transformed her relationship with her estranged adoptive mother. Ozawa-de Silva and Dodson-Lavelle hope that this work will lead to training for educators and caregivers to implement the practice of compassion meditation in a range of settings.

Raison also reported to the Dalai Lama on a new study now under way, designed to test the value of meditation in reducing the types of physical and emotional responses to stress that increase disease risk. The Compassion and Attention Longitudinal Meditation Study (CALM) will help scientists determine how people’s bodies, minds, and hearts respond to stress and which specific meditation practices are better at turning down those responses. “Data show that people who practice meditation may reduce their inflammatory and behavioral responses to stress, which are linked to serious illnesses including cancer, depression, and heart disease,” says Raison, who is principal investigator of the study.

The CALM study has three different components. The main component, which is funded by a federal grant, compares compassion meditation with two other interventions—mindfulness training and a series of health-related lectures. Participants are randomized into one of the three interventions.

A second component involves the use of an electronically activated recorder (called the EAR) that is worn by the participants before beginning and after completion of the meditation interventions. The recorder will be used to evaluate the effect of the study interventions on the participants’ social behavior by periodically recording snatches of ambient sounds from their daily lives.

The third component involves neuroimaging of the participants to determine if compassion meditation and mindfulness meditation have different effects on brain architecture and the function of empathic pathways of the brain.

Mastering meditation takes dedication and time. “Meditation is not just about sitting quietly,” says Negi. “Meditation is a process of familiarizing, cultivating, or enhancing certain skills, and you can think of attentiveness and compassion as skills. Meditation practices designed to foster compassion may impact physiological pathways that are modulated by stress and relevant to disease.”

Raison and Negi hope to show that centuries of wisdom about nurturing the inner mind, combined with Western science about how the body and brain interact, can have a positive impact on personal well-being and health.